What Else Must Be True?

The Year of Puzzles

2025 was a year of puzzles for me. Literally, not metaphorically. I wrote about crosswords in September and The New York Times’ Spelling Bee in February.

Today, I need to tell you about Clues By Sam.

Clues by Sam is a logic puzzle that features a 4x5 grid of tiles. Each tile has an avatar, name, and profession. Using the provided clues, you have to figure out whether the person on each tile is a criminal or an innocent. The starting clue might be something like “Tara is one of 3 criminals in Column C.” You label Tara a criminal, which reveals the next clue. Clue by clue, you figure out the status of all 20 tiles.

Like daily crosswords, the Clues by Sam puzzle gets more difficult as the week progresses. On Monday, the puzzle is pretty straightforward. Most clues point to the next tile you can label without much mental effort. By Thursday, you’ll need to hold the implications of multiple clues in your mind to figure out the next tile’s status.

In my head, that sounds like “If X, Y, and Z are true, what else must be true?”

Not coincidentally, this is how I think about all decision-making—and especially the decisions that go into business strategy.

Choices In Context

If you’re reading this around the time it comes out, well, I suspect you’ve got some decisions on your mind. Or perhaps, you finished off the last year with some big decisions about how you want to begin this year.

Even if you’re not listening to this in January 2026, there’s a good chance you’re in the process of making a significant decision. And decision-making is what I want to talk about today… not so much how to choose, but the context of our choices.

No decision gets made in a vacuum. Choices are always framed by circumstances, relationships, emotions, fears, and desires.

Based on what I’ve observed and experienced, I think there’s a category of decision for which we intuitively consider that context. Most of us wouldn’t, say, take a job on the other side of the country without talking to the other people that decision would affect. Most of us wouldn’t throw in the towel on a relationship after one fight without weighing that experience against a history of emotional dynamics.

We weigh our options given everything else we know.

But there are some types of decisions for which all of that intuition and skilled balancing flies right out the window. These are the decisions we have to make about things we’re less-than-confident about—choices that provoke anxiety or pick at old failures.

In my own work, I see the decision-making process break down when it comes to business decisions. Either folks have very little context to go on, or their context is littered with choices they now regret, or they simply don’t know how to connect the context they have to the options in front of them. One common result of this breakdown is flailing about trying to find the “right” choice. Another is doing whatever it seems everyone else is doing. Still another is simply ignoring the need to make a decision.

Rarely is the next move taking a step back to ask, “What’s really going on here?”

I suspect this isn’t a problem that only business owners have.

When the stakes are high—emotionally, financially, socially, even narratively—and our confidence wanes, we go searching for the right answer rather than giving ourselves the grace to get creative with what we already know, the way we might if the stakes were lower or our confidence was higher.

Sometimes the stakes are high, as they can be with consequential career or business choices. Sometimes they only appear high because we don’t know enough to understand the true stakes. Situations that are unfamiliar or even mysterious feel especially weighty because we assume that their lack of transparency is a sign of their importance. Or that our lack of knowledge is a sign we’re in over our heads and that one wrong step could lead to our demise.

I have good news, though. Self-knowledge is knowledge we can bring to bear on unfamiliar situations. And often, self-knowledge is the kind of strategic constraint we need to limit our options enough to focus our research or game out our options.

That’s why I start any business strategy development by getting to know the business owner’s needs and priorities. How much do you want to earn? And how important is that number to you? How flexible do you want your schedule to be? And how important is that flexibility to you? Do you prefer to fill your time with people or with projects? And how important is that preference to you?

Again, I’m talking about business strategy here—but this approach applies to all sorts of other scenarios.

By getting clear on your needs and priorities, you build a solid foundation for every other decision to come. You have at least that context to fall back on when weighing your options.

What follows is an adapted excerpt from my new guide, Blank Slate, which helps small business owners and freelancers start fresh, challenge assumptions, and rethink their work for long-term sustainability. I’ll share my favorite question for business strategy development and explain why knowing your needs and priorities is the key to making business decision-making easier.

Even if you’re not a business owner, I suspect the mental model I share will be useful in other aspects of your work or life.

Your Needs & Priorities

When it comes to building (or rebuilding) a business, you’ve got a lot of options. So one of the biggest challenges is simply making decisions about the thing. Often, you don’t even know what all of your options even are, let alone how to choose between them.

Strategy is an architecture for decision-making. Strategic choices give us a scaffold that makes subsequent decision-making easier. They lay a foundation of decisions we can then build on. And as Maren Morris says, “The house won’t fall if the bones are good.”

As I mentioned earlier, I always start building this foundation by taking stock of personal needs and priorities. This is an extreme simplification, but there are essentially two ways of looking at building a business: (1) as a money-making venture and (2) as a needs-meeting pursuit. When we frame business-building in terms of making money, it shapes how we perceive our options and often leads us down paths that, while successful, leave us exhausted, unsatisfied, or even miserable. Needless to say, that’s not sustainable.

If, instead, we frame business-building as a needs-meeting pursuit, we have to ask whose needs we’re trying to meet and what those needs actually are. They’re our needs, our customers’ needs, our team’s needs, and our community’s needs. I start with the owner’s personal needs because if those needs aren’t met or exceeded, they won’t be able to address other needs.

If your needs (and preferences) are not at the center of how you conceive of your business, your later decisions won’t reflect what’s most important to you. The only way to achieve long-term sustainability is by making sure your business takes care of you.

To explain, though, I need a different metaphor. So get in, business owners:

We’re Going to Algebra Class

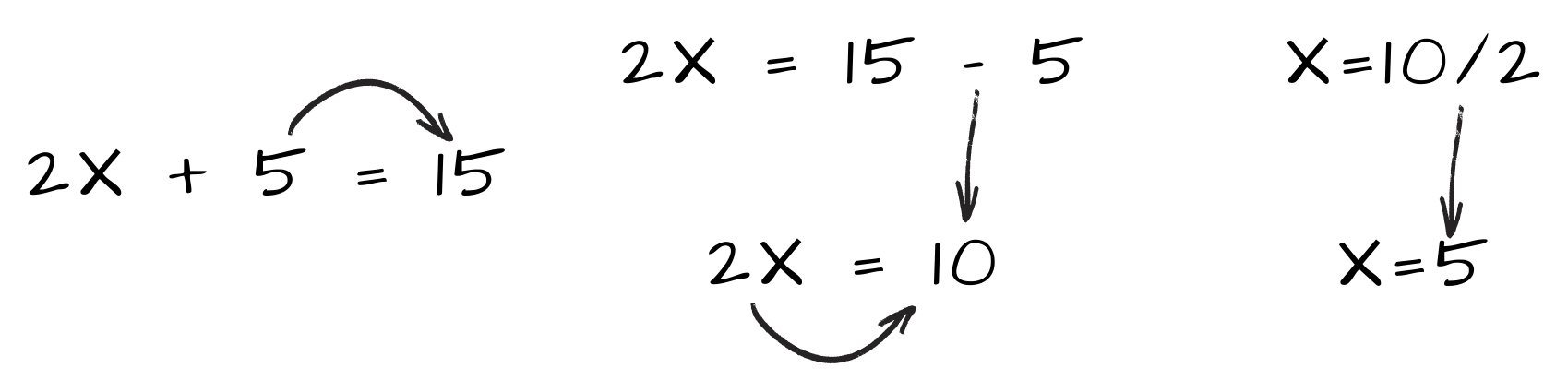

You can think of your needs and priorities as constants in a multi-variable algebra problem. Okay, don’t panic. Try to remember back to junior high math class. If you’re given the equation 2x + 5 = 15, x is the variable, and 5 and 15 are constants. To solve the problem, you manipulate the constants to get to the value of x. It would look like this: 2x = 15 - 5 then 2x = 10 then x = 10/2 then x = 5.

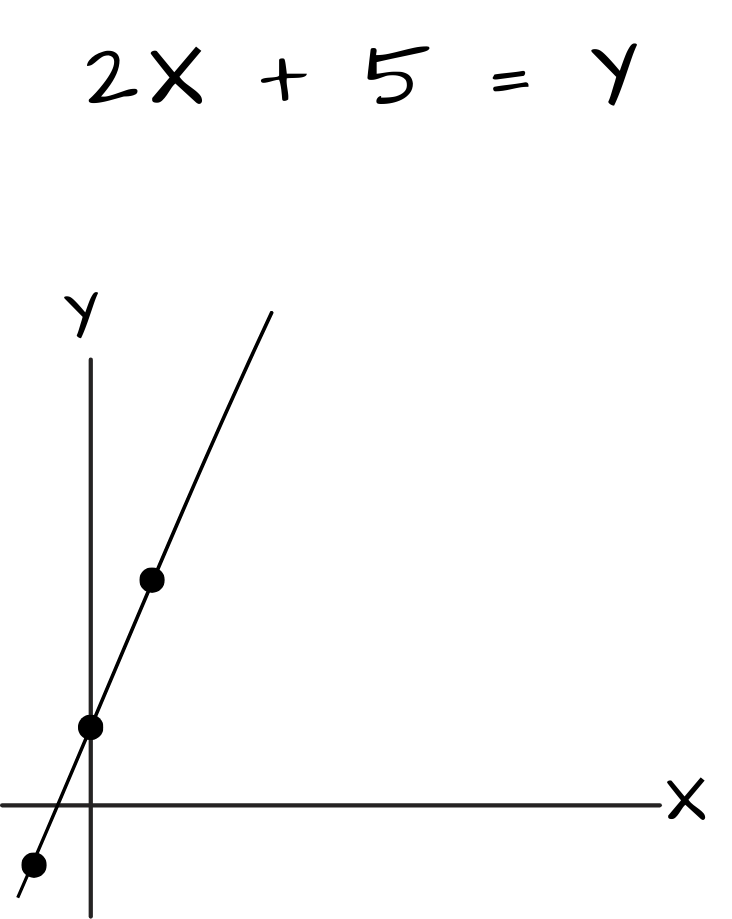

Now, if your algebra equation has two variables (e.g., 2x+5 = y), there isn’t a single way to solve for x or y. Instead, you get sets of solutions that can be depicted as a line on a graph. So (5, 15) is one answer, (20, 45) is another, and (-5, -5) is another. You can graph the line, but you can’t arrive at a particular answer without substituting a constant for one of the two variables. If y = 45, then x must be 20. There are an infinite number of solutions, but the answer can’t be anything. Once a variable is decided on, the other variable is also known.

When you identify your needs and priorities for your business, you’re converting one of many variables into a constant, which then limits the possible solutions for the equation as you move on. Each variable you solve for is important, but the most fundamental—and therefore the one we start with—is what you need or want your business to do for you.

What else has to be true?

For example, imagine your most important personal variable is that you work with clients only one day per week so you have maximum flexibility the rest of the time. With that established, you can ask yourself: If I only work with clients one day per week, what else has to be true? There are many ways to answer that question, but even that one variable constrains your choices and makes the next variable just a little easier to solve for: If I work with clients one day per week and I need to generate at least $120k in personal income per year, what else has to be true? If I work with clients one day per week, need $120k per year, and have the capacity for six concurrent clients, what else has to be true?

From there, you can imagine how these first choices impact a slew of other variables: the type of people you work with, the way you structure engagements, the prices you charge, the expectations you set, the people you hire, etc. And if it’s not clear yet, that’s okay—stick with the process, and you’ll get the idea.

Now, is it possible that you start identifying your needs and priorities only to end up with a scenario in which there’s no good answer to “what else needs to be true?” Sure. It’s unlikely, but possible. More likely than ending up with an unsolvable equation is ending up with an equation you don’t like the solution to. You find yourself backed into a strategic corner, and the next move is one that violates your values or preferences. In that case, this same process allows you to back track and make adjustments to open up new possibilities.

For example, maybe you would prefer to work with more than 6 clients—but you still need to keep to just one day per week of client work. If you work with clients just one day per week, generate $120k per year, and have the capacity for 24 clients, what else must be true? Well, probably that you work with 4 groups of 6 clients each on that one day.

Below is a simple (if not easy) exercise that will help you name your needs and priorities. But first, one note of caution. It’s common to try to find the “right” answer here. When it comes to your needs and priorities, there is no right answer other than the one that is an honest reflection of your needs.

Further, there’s no need to limit yourself to what feels “realistic.” You don’t know what’s actually realistic until you put together a scenario and figure out what it would take to make it happen. Finally, don’t try to game the process. You might think you can input answers early in the process to get your desired outcomes later on, but you’ll just end up frustrated and stuck.

Answer truthfully. Be honest. Get creative.

Base Case & Best Case

Grab a piece of paper or open a blank document. Divide it length-wise so that you have two columns. At the top of the left column, write “Base Case” and at the top of the right column, write “Best Case.”

Down the left side of your paper or document, you’ll write down several categories for your needs and preferences.

For each category, you’ll describe your base-case scenario and your best-case scenario. Your base-case scenario is one in which you feel secure, supported, and comfortable remaining in for years. It’s not merely “good enough” but sustainable and satisfying. Your best-case scenario is one in which you feel you and the business are functioning well above baseline and fully aligned with your values and worldview—not necessarily cruising on your personal superyacht.

Income: What do you personally need to earn from your business? What does that number represent?

Type of Work: What skills or strengths do you want to use daily? Weekly? Monthly?

Schedule: Do you prefer a stable and predefined schedule? Or do you need flexibility? How much flexibility do you need? Why?

Customers: Who do you want to work with? What kinds of problems or goals do you get excited about working on? Who inspires you to do your best work?

Career Goals: How does your business need to shape your longer career trajectory? What do you want professionally from running your business?

Community: What community or communities is your business part of? That could be local, interest-based, identity-based, or any other way you define the community context of your work. How do you want your business to integrate into your community?

Predictability: Do you need your business to be more stable and less risky? Or do you prefer to take some risks and leave the possibility of surprises open?

Health: What mental or physical health needs does your business need to accommodate? What kinds of rest should be built into how you develop your business? What kinds of projects energize you?

Team: Do you prefer to work with others or on your own? Do you want help with certain ancillary tasks? Or do you need team members who can own more complex projects?

I suggest taking 15-20 minutes to do a quick first pass on the exercise—jotting down whatever comes to mind. Then, take a break and come back to spend more time with it. Aim for more specificity and ensure that what you’re describing actually meets (or exceeds) your needs.

Finally, take at least one more pass after a day or two.

Get Curious

Frankly, most of us are out of practice at putting our own needs and priorities first. So taking your time with this kind of exercise, letting your answers slowly come into focus, and imagining new possibilities is really important.

Once you’ve done that, take a look at your work again and circle the three categories that are most important to you—the non-negotiables. All of the other categories might be important, too! But they’re the ones that could stand up to a little compromise in the short-term.

One category at a time, ask yourself, “If this base-case scenario must be true, what else must be true?” For example, “If I need a high degree of predictability, what else must be true?” Or, if I need to minimize the time I spend on Zoom, what else must be true?”

The, focusing on your top three categories together, ask yourself, “Given these needs and priorities, what else must be true about my business?”

Finally, consider a decision you’re wrestling with right now. Given the needs and priorities of your top categories, what must be true about the decision you make?

One More Thing

Remember, self-knowledge is critical to making sustainable choices about how you build your business (or make other personal or professional choices). Self-knowledge isn’t the only context bearing on your decision, but it’s easily overlooked despite how often it can steer you in a productive direction.

Building a business may be a puzzle, but it’s not one without clues. Given everything you know, what else must be true?

Introducing Blank Slate

This exercise is adapted from my new guide, Blank Slate. Blank Slate guides you through a progressive process of challenging your assumptions and rethinking your small business so that you can develop a strategy that’s clear, decisive, and sustainable. It’s a guide more than a decade in the making, drawing on the workshops, courses, and coaching I’ve developed over the last 17 years.

It’s a permission slip. A confidence boost. And a business coach in your proverbial pocket.

Blank Slate is a 100+ page workbook that comes both in color for working on tablets and printer-friendly grayscale for working by hand. You also get an audio version and exercise-only workbook so you can do your thinking wherever you prefer.

Blank Slate launches on Thursday, January 15. But you can pre-order it now at an early bird price.