3 Ways I Make Sense of the Unexpected & Perplexing

Sensemaking may start with chaos, but that doesn’t mean chaos always arrives with a blaring alarm or flashing red lights. That is, frustration and confusion can become so commonplace that we fail to recognize when we’re experiencing chaos. They simmer just below the surface, papered over by convenient narratives and clichés.

Here’s what I mean.

A ubiquitous childhood complaint is, “That’s not fair!” A child is keenly attuned to fairness. They believe authorities should mete out rewards and punishments in a predetermined and just way. They expect that what one child gets, another should also get. If one friend gets to go to the party, all the friends should get to go to the party.

The exasperated and perhaps cynical parent responds to “That’s not fair!” with “Life isn’t fair!” At first, the child remains frustrated and confused. They won’t accept that fairness isn’t a guiding ethic outside the kindergarten classroom. But over time, a lack of fairness explains much more than an ethic of fairness can. They accept it; life isn’t fair. Unfairness is just normal life.

To a child, unfairness is chaotic—unexpected and profoundly frustrating. To an adult, unfairness is just the way it is, no matter how much we might like it to be otherwise. Unfairness doesn’t feel like chaos because we expect life to be unfair. We bury our childlike frustration so we can get on with life…

…until the chaos bubbles up, sometimes slowly and other times explosively.

We become adept at sidestepping confusion and living with cognitive dissonance. And while that avoidance serves a purpose, it doesn’t ultimately make our lives better. It certainly doesn’t equip us to change our little corners of the world for the better.

Learning new mental models, new ways of making sense of the world around us, helps us not only notice our frustration in productive ways, but it also helps us take the first steps toward change.

I think I’ve always been interested in integrating new mental models into my understanding of the world. It’s why I have a degree in religious studies. It’s why I’ve interviewed hundreds of small business owners about how they think. It’s why I read theory and listen to podcasts that help me apply new concepts to old frustrations and current events.

In the second part of this mini series on sensemaking and media, I want to share three of the mental models I use to notice, analyze, and critique the systems that frustrate or confuse me. I often use these in my writing, but I also use them with clients, with my daughter, and with pretty much anyone who will listen to me (thank you).

These models aren’t even the tip of the iceberg when it comes to all the different ways we can make sense of the world. But I do think they’re ones you can apply broadly and start using quickly. Or, you might notice that they’re models you’re already using and now can be more conscious of how you deploy them.

Speaking of which, if you want to communicate with more clarity, create more persuasive messaging, and stand out from the crowd with rigorous thinking, check out Making Sense. Making Sense is my 8-week interactive workshop that walks you step-by-step through creating media that helps others make sense of the world. Whether you’re a writer, podcaster, creator, academic, marketer, or any other kind of media maker, you’ll learn new tools for producing content that offers others some relief from the confusion and frustration they feel.

So buckle up—here’s how I make sense using the “man behind the curtain” framework, the process of normalization, and the theory of value capture.

“Man Behind the Curtain” Framework

Last week, a client expressed their frustration at the absolute drivel (my words) that passes for “good content” on LinkedIn. Specifically, they expressed that that’s the kind of thing people want to see on that platform—and my client just wasn’t interested in making or engaging with it. I completely agree that the average LinkedIn post is a dumpster fire fueled by hustle culture and AI-summarized productivity books. But I had one quibble.

My quibble—okay, it’s more than a quibble—is that just because that kind of content is ubiquitous and popular, it doesn’t mean that people want to see it. Instead, the presence of this particular type of drivel means that posters have figured out that this type of post is more likely to meet the criteria that the LinkedIn algorithm selects for. Likers and commenters have, in turn, learned that engaging with those posts helps to boost their own content. Not only do they feed the algorithm with engagement data, they also create more of the same kind of post, hoping for the same effect.

As algorithmic feeds replaced chronological and follower-based feeds, platforms had to teach us why this was a preferable approach to viewing content. While the old message was, “We’ll show you what your friends and family are up to so that you can stay in touch,” the new public-facing message had to be “We’ll show you the stuff you really want to see.” We went from engaging with these platforms with a “friends and family” mental model to a mental model featuring an algorithm that was just trying to make us happy.

Of course, that was just the public-facing message. The operational model prioritizes value production by getting us to spend as much time on the platform as possible. Yes, sometimes that operational model and the mental model we intuited from it (that the algorithm was showing us popular content) overlap. I mean, the odds that I get sucked into the first video I see when I open up TikTok are pretty high. But more importantly than my interest in that video is that I scroll to see the next one, and the one after that, and the one after that.

To properly contextualize the content I see on an algorithm-driven platform, I have to consciously remember to apply a mental model based on stickiness—on the chances that I will stick around longer based on what I see (good or bad). So it’s not accurate to say that the content on LinkedIn is what people want to see. Instead, we should deduce that the content on LinkedIn is keeping people engaged longer.

Creating content that keeps people engaged on LinkedIn is a very different thing from making content people want to see. Further, when we stop believing that this is what people want, we can unlock a less cynical view of the people we encounter on these platforms—even a less cynical view of the people creating the content we roll our eyes at.

Recontextualizing inferences like this one—that the algorithms privilege content people want to see—is an example of a mental model I often reach for. We might call it the “man behind the curtain” framework.

When Dorothy and crew finally make it to Oz and visit the wizard, they are met with a mysterious green visage flanked by flame. The wizard is intimidating—”great and powerful” indeed. Of course, Toto gets curious about what’s going on behind a curtain on the edge of the great hall and reveals that behind the curtain is a bumbling old man with no magical powers to speak of. He professed his “great and powerful” nature, but could only express it as a façade. His nature, as expressed in his person, was that of an ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances.

How to use this mental model

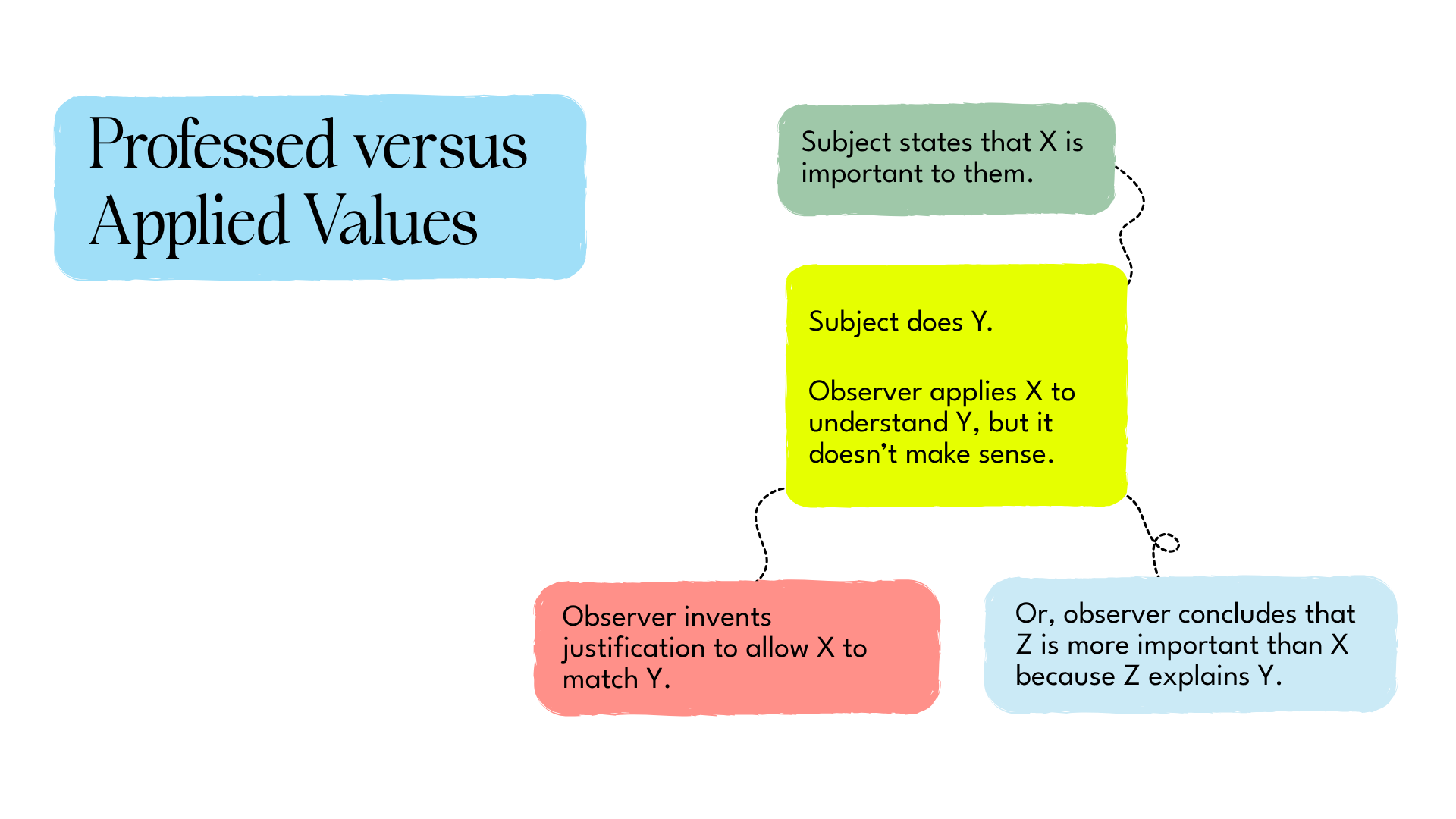

We can make sense of many of today’s more chaotic scenarios by applying the “man behind the curtain” framework. There’s a public-facing value message and an internal operational application of some other value. The disconnect between those two values is what creates the confusion, frustration, or cognitive dissonance we feel.

What’s more, spin doctors often cover up some less than savory values with more palatable messages: safety stands in for racism, economic freedom stands in for exploitation, protecting the kids stands in for homophobia and transphobia, health and wellness stand in for fatphobia or ableism, etc. That’s not to say that everyone who speaks of safety, freedom, protecting children, or wellness is camouflaging bigotry, but that it’s helpful to ask whether that’s going on behind the curtain when encountering those messages. Is it the wellness movement or the existing ableist preferences in disguise? Is it being done in the name of safety, or is it operationalizing the fear of the other?

Back to the LinkedIn example, corporate and stakeholder interests are often the value hiding behind a benevolent, customer-friendly message. The professed value is to deliver you the content you want to see. But the applied value is to deliver you the content that will get you to look at the most ads.

This bait-and-switch works because sometimes the switch is nearly indistinguishable from the bait. Sometimes the man behind the curtain makes something seemingly magical happen. But that doesn’t make him a great or powerful wizard.

The Process of Normalization

Our cultural memory is quite fleeting. We forget that all manner of things we think of as “just the way it is” weren’t the way it was a short time ago.

For instance, the idea of hopping in a car and driving somewhere I’d never been before without a cell phone is almost unthinkable. Yet, between the ages of 16 and 20, I did it all the time. Until I got my first smartphone when I was maybe 27 or 28, even when I had a phone with me, I was still printing out MapQuest directions and hoping for the best.

The cell phone as a necessary appendage for travel is completely normalized now. Going without it seems strange, even unnecessarily risky. We even joke about it: ‘Can you believe we used to drive an hour away without a smartphone?!’ This is the normalization process at work.

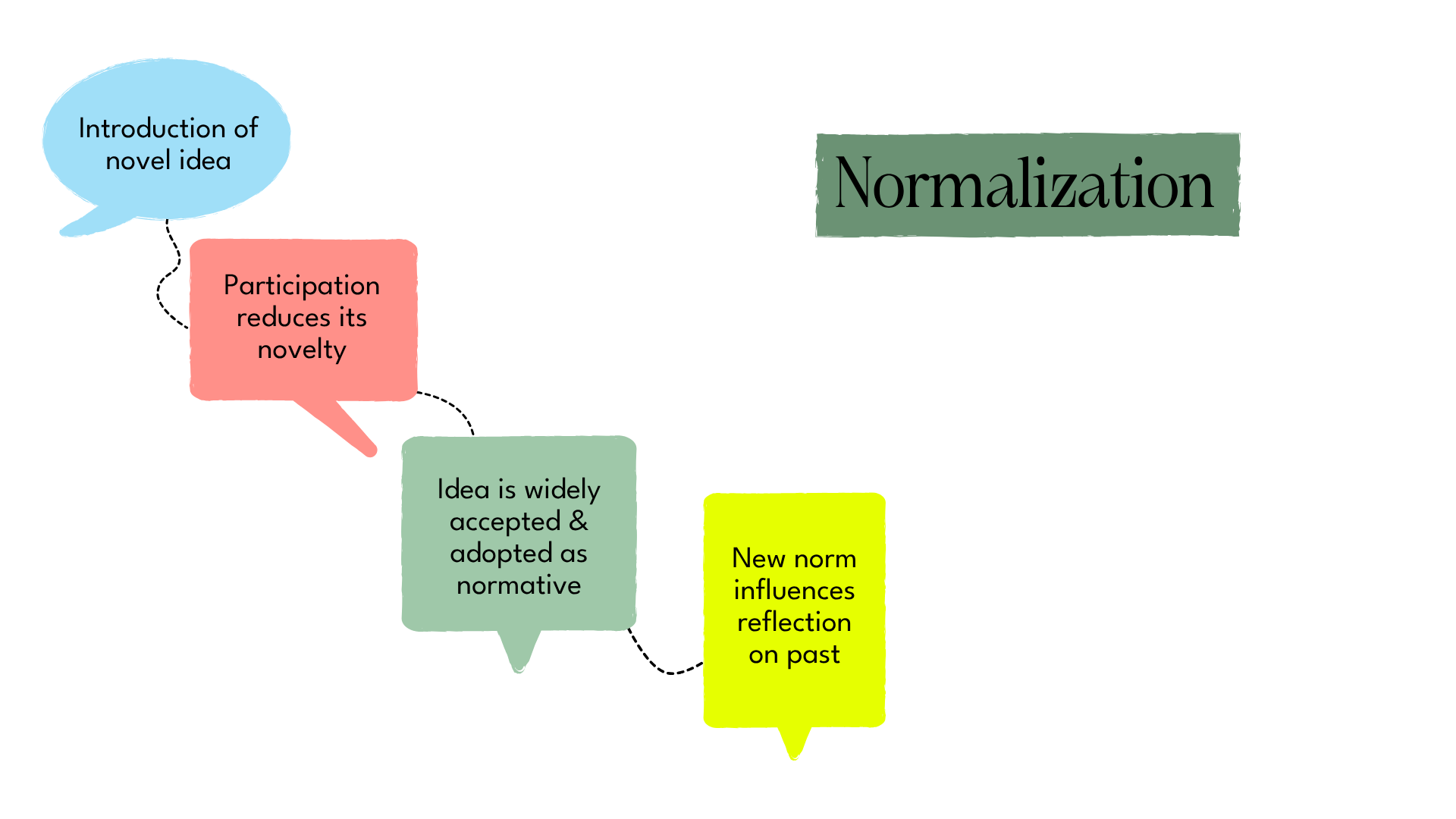

Normalization occurs when something new or novel becomes fully integrated into our lives in a way that makes forgoing it or choosing differently seem absurd. It happens with technology all the time. But it also occurs with beauty standards, clothing items, education, gender, family structure, etc.

Norms are socially constructed, and normalization is a social process—meaning, we do it together. What is a norm is, by definition, not something that an individual decides on. It takes a group to establish a norm.

How to use this mental model

When we understand what’s “normal” as contingent social constructions, we can use them to make sense of all sorts of frustrations. While we often talk about normalization as a process that occurs on the societal level, it impacts much more personal frustrations too.

For instance, for-profit, employer-based health insurance is normalized in the United States—that has, indeed, occurred on the societal level. But its impact on Americans’ lives is deeply personal and incredibly intimate. The only way to relieve the chaos of getting a ginormous bill from your doctor or dentist is to rely on this norm—‘that’s just the way it is.’ It might seem unfair, but we understand that’s the risk we take as people with bodies in the US. The chaos becomes commonplace, and we accept that it’s possible to pay through the nose for health insurance and still be on the hook for thousands of dollars in actual care.

Of course, that partially relieves the chaos, not the financial burden. By denormalizing the US healthcare system, though, we can agitate for change and convince others of the need to join the cause. What I mean by “denormalizing” or “denormalization” is calling attention to how we’ve constructed this reality that frustrates and confuses us. Through denomalization, we make what passes for “normal” appear abnormal, or weird, or just plain invented. Because it is.

Denormalization is also a great model for changing things like your personal habits or workflows. For instance, if you find yourself checking your email constantly or feeling the need to respond to messages long after the workday is done, you might notice that always-on communication has become normalized for you and for those you work with. You may believe that’s “just how it’s done.” But business was being done and clients were being taken care of long before always-on communication became the norm. So you denormalize that habit—you make it weird—and ask yourself how you could do things differently or what guardrails you could put in place.

Normalization doesn’t only occur in ways we perceive as negative. Working from home, for instance, has been a positive process of normalization for many people. Sharing the pronouns you use is normalized in certain groups and circumstances. Diagnoses like depression, anxiety disorders, ADHD, autism, and OCD are becoming normalized in ways that reduce stigma and encourage support.

One of the reasons I lean on normalization as a mental model is that a little historical curiosity can put any normalized behavior or perspective in context. Normalization can be hard to spot by its very nature, but it’s easy to demonstrate once you notice it. A couple of years ago, I wanted to make sense of the bizarre refund policies that influencers attached to their online courses. I let my historical curiosity lead the way—straight to Josiah Wedgwood, who is cited as having the first money-back guarantee in the nascent consumer economy. By connecting the historical dots, I was able to show how refund policies were normalized over centuries and how the refund policies I found so perplexing were a reversal of the logic that once inspired guarantees in the first place.

The other reason I lean on normalization as a mental model has to do with its ability to not only explain how we got here, but also provide a road map for going somewhere else. Once you realize that the subject of your consternation is socially constructed over time, it’s possible to ask what we might construct in the future.

The Theory of Value Capture

Here’s a Zen koan for you:

If you go for a run without your smartwatch, did you go for a run at all?

Intellectually and physiologically, I know that I ran. Psychologically, though? The jury is out.

For those of us who have become, let’s say, attached to our watches, the idea of not tracking a workout can be anathema. Now that I’ve upgraded to an Ultra 2 with far more battery, my attachment has extended to sleep. How will I know if I got a good night’s sleep if my watch doesn’t tell me?

I would very much like to tell you that I am exaggerating here—and on some level I am—but these are very real if not rational anxieties I have. The fact that I’m aware of it and have a way to explain this phenomenon certainly makes it less destructive, but it doesn’t make those anxieties go away.

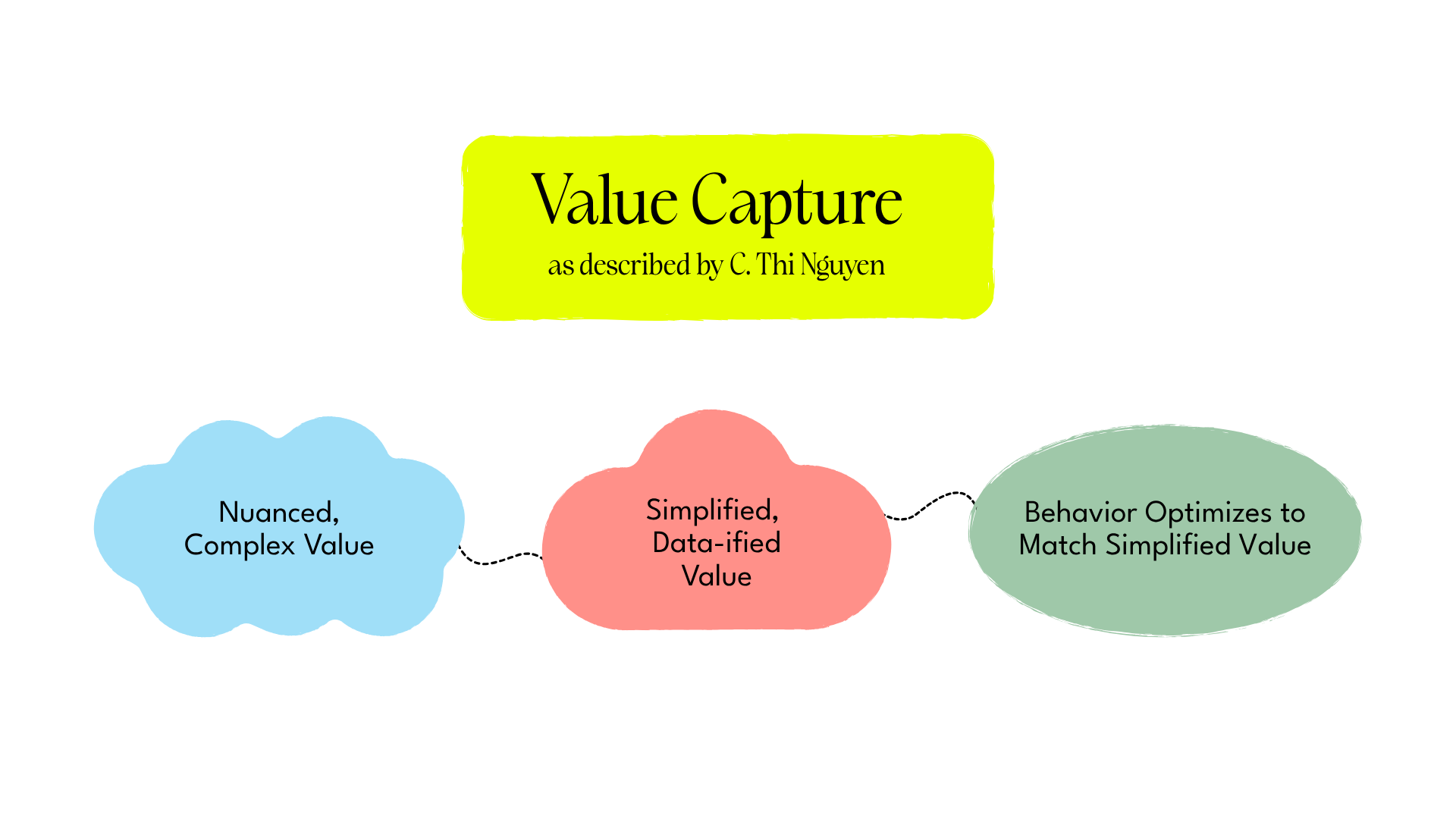

I can make sense of this phenomenon thanks to the mental model that philosopher C. Thi Nguyen developed called value capture. I’ve written about this many times, including in my book, because it’s such a useful mental model for making sense of the variety of anxieties and obsessions that stem from data. Nguyen first described it in the context of understanding how games operate, then applied it to how discourse evolves (or rather, devolves) on social media.

Here’s how it works. First, we have a value—in this case, something that’s important to us—that’s rich and nuanced, like health, learning, or friendship. It’s probably quite difficult to describe succinctly, and we might even disagree a bit on what it is. Second, we have a need or desire to better understand this value, often at scale, over time, or for comparison. So we create a system for quantifying that value. Nguyen often cites GPA (grade point average) as an example; we value learning and want to evaluate whether a student is learning and compare their learning to other students’ learning. GPA is a system for quantifying educational achievement.

Of course, any quantification of a nuanced, rich value must be limited in scope. It’s handy for all the reasons data is handy, but it fails to capture the full depth and breadth of a rich value. In the case of school grades and GPA, that is going to correlate with a narrow form of intelligence and a particular type of learning. But because GPA is so normalized (see what I did there?) as a measure for intelligence and learning writ large, we give it much more substance than it ultimately deserves. Having a high GPA doesn’t mean a student is exceptionally intelligent or even that they learned a lot in their classes. It means they produced the behavior that leads to good grades.

That shift from trying to evaluate a nuanced value to inadvertently incentivizing behavior specific to the evaluation rather than the value is the third part of the value capture process. Once a measure is fully normalized, we tend to prioritize the behavior that produces positive metrics rather than the value we initially set out to measure. Today, students don’t prioritize learning so much as they prioritize getting a good grade on a test. There are ways to do both, but you don’t necessarily have to learn to get a good grade.

When we encounter the chaos of a student who performed well in high school but is struggling in college, for instance, we might make sense of that by noting how testing in high school and evaluation in college are quite different. The student optimized their behavior for high school testing and needs to recalibrate to succeed in college.

How to use this mental model

Another example is corporate stock prices. A company should value the health of the business—happy customers, loyal employees, solid governance, etc. Over time, stock price trends came to stand in for the health of a business. In short order, CEOs learned that stock prices could be manipulated through behaviors that did not improve the health of a business (and often put it at grave risk). When we encounter the chaos that comes from something like mass layoffs (typically a sign that a business isn’t doing so hot) leading to higher stock prices, we might make sense of that by reminding ourselves that stock prices are really about increasing shareholder wealth rather than measuring the health of a business. The CEO is merely optimizing their decision-making for that paradigm.

Okay, one more example—this is really an incredibly useful mental model!

Let’s say you’re trying to get customers for your small business. You’ve heard that social media is a good way to do that. So you start posting. You figure out how to get more followers for your account and more likes and shares on each post. Because these are the most visible metrics, you start to adjust your content to get more and more followers, likes, and shares. But then you notice that you haven’t gotten any customers from the work you’ve done on social media. That’s confusing—you believed (consciously or not) that maximizing your social media metrics would translate into new leads. You substituted followers, likes, and shares for a rich, nuanced value like interest or even attention.

Your content wasn’t designed to attract customers; it was designed to attract followers, likes, and shares. You wanted customers, but you behaved as if you wanted likes. That’s value capture.

As our institutions, social relations, and personal lives have become more and more data-ified, more and more machine-readable, value capture has become ubiquitous. We love to be able to plug numbers into spreadsheets and rank things. We love it when data seems to provide the “right” answer to a question that seemed impossible to know. Data and their analysis feel clarifying and objective. And data can be really helpful—just not at the expense of what matters most.

When you encounter chaos as a result of value capture, ask yourself what metric seems most important, whether that metric actually measures what matters, and what value actually matters. Untangling value capture can help you take more effective action, create new ways to evaluate progress, and return to a richer, more nuanced set of values.

Last Thing

These three mental models—the “man behind the curtain” framework, the process of normalization, and the theory of value capture—aren’t discrete. They overlap and inform the others, as do a host of other mental models useful for making sense of chaos. And sometimes chaos can’t be explained by existing theories. We need new mental models to explain emerging forms of chaos.

Further developing our awareness of and fluency with mental models gives us more tools to work with. In the previous episode, I mentioned that you are already making sense for others all the time. You see things differently from your client, child, partner, parent, or coworker because you have a different mental model for making sense of it.

But just like not all chaos is obvious, not all sensemaking is obvious either. And the mental models we use to process incoming information more effectively than those who look to us for help certainly aren’t obvious.

That is, unless we practice paying attention to them. The more we notice the mental models we use to make sense of chaos, the better we get at making sense for others. The more fluent we become with the mental models we use, the more we’re able to apply them to a wide variety of perplexing and frustrating situations.

Making Sense: An 8-Week Interactive Workshop

In the meantime, if making sense is something you know you want to do more of for people you care about, check out Making Sense—an 8-week workshop on turning meaningful ideas into remarkable media. Step by step, I’ll help you identify the ways you already make sense for your audience, team members, stakeholders, or students so that you can create articles, videos, podcasts, white papers, or social media posts that make a bigger impact.