Breaking The Validation Spiral: A Systems Approach

“The aim of each thing which we do is to make our lives and the lives of our children richer and more possible. …my work becomes a conscious decision—a longed-for bed which I enter gratefully and from which I rise up empowered.” — Audre Lorde

The fifth grade was a bit of a breaking point for me. I loved both of my fifth-grade teachers—Mrs. Osif and Mr. Keim. I felt seen by them in a way I hadn’t felt seen by other teachers. I can’t know for sure, but I think they noticed I was struggling. Not with school work. But with my self.

I remember sitting in the back of Mrs. Osif’s room working on a project I couldn’t quite let go of. I was painstakingly building an amusement park out of construction paper, reveling in every small detail I could translate into the inelegant medium. Autistic hyperfocus—that’s what I would call it now, though no one had that vocabulary for me in the early 90s.

What it felt like was excellence. It felt like letting the whole of my creative and productive capacity loose on a single idea. It felt satisfying.

In hindsight, I’m pretty sure that whole project was the kind of red flag that autistic girls so often raise for teachers and parents. An indication that something is off—but maybe in a good way? Like, we’re pretty sure this is bad, but we’re also pretty sure we shouldn’t try to correct it?

It was no coincidence that my mom was discussing the possibility of me skipping sixth grade at the time of this memory. The euphemism we always used to talk about my struggles in school was that I wasn’t being challenged. I needed a challenge to fix my focus on, to direct my resources toward. I needed more of the excellence I experienced in my rigorous obsession with my construction paper amusement park.

I skipped sixth grade, but I didn’t find a challenge waiting for me in junior high. I know now that that’s not really the function of public schools in the United States. But that’s a topic for another day.

That need for a challenge, the desire for excellence, the longing for deep and abiding satisfaction—that is universal. Being able to apply ourselves to the work of rising to the challenge and creating the satisfaction of excellence is, as theologian Gregory Baum put it, “the axis of human self-making.” Unfortunately, this isn’t often the kind of work on offer. Not in the job market, not in the world of business, not in the home or the school or the gym. We are overwhelmed, but not challenged. We are busy, but not satisfied. We are hard at work, but hardly working toward excellence.

Audre Lorde wrote that embracing excellence means going beyond “the encouraged mediocrity of our society.” That begs the question:

How does society encourage mediocrity?

Considering the cultural production devoted to self-improvement, entrepreneurial mythmaking, and ever-bigger goal-chasing, it might seem like society encourages everything but mediocrity. However, this misunderstands what creates the conditions of mediocrity and the role that mediocrity plays in the economy. Mediocrity isn’t a personal failing or insufficiency; it’s the inevitable result of how we misallocate resources because we tie personal validation to performance.

The good news is that while we may not be able to magically change the imposed conditions that create mediocrity, we can dismantle the feedback loop that prevents us from embracing excellence.

Before we go any further:

What is mediocrity?

Mediocrity is a discrepancy between reasonable expectations and the capacity we have to fulfill those expectations. It’s a complicity with the insufficient, an acceptance of conditions as they are. Mediocrity is risk-averse and change-resistant.

We typically hurl “mediocre” as an insult toward people, institutions, or objects that fail to live up to our hopes and expectations. And it can become a very sticky label. However, I prefer to view mediocrity as a disposition—a way of perceiving a situation that can be altered at any time by questioning the status quo or creatively rethinking our priors.

One way we might define mediocrity is as a state of dissatisfaction. We experience something as mediocre when it feels somehow incomplete or when it meets only the bare minimum of expectations. It might get the job done, but never in a satisfying way.

Satisfaction, as Lorde argues in the same essay, is critical to transcending mediocrity. If “satisfaction and completion” are sources of power and knowledge, then mediocrity relinquishes that power and denies that knowledge. It’s a kind of ignorance that allows us to remain complacent despite the yearning for something more.

The continued production of mediocrity has a political and economic function. Put another way, the continued denial of satisfaction has a political and economic function. Satisfied people aren’t rampant consumers. They’re not workaholics. They’re not voters who accept the nonresponsiveness of their representatives. They’re not workers who dutifully meet ever-increasing management expectations.

Mindlessly tracing the circular path of mediocrity keeps us buying and working while paying no attention to the man behind the curtain.

The Validation Spiral

In the 21st-century economy, mediocrity doesn’t often appear lazy or comfortable. It’s not unproductive, entitled, or even quiet quitting. Most often, mediocrity is busy—overworked and under-rested. It’s a perpetual state of insufficiency, but not from lack of trying.

In my book, I outline what I call the Validation Spiral. The Validation Spiral arises from the universal motive that I described earlier, the longing for excellence and satisfaction. But that motive gets translated into the language of transactions—as so many other aspects of life do. Our longing for excellence and satisfaction becomes the impulse to feel useful and literally valued.

In our pursuit of usefulness (and its accompanying validation), we commit to responsibilities and projects. Those commitments can be work-related, but they can also be social, family-oriented, political, athletic, creative, and so on. We follow through on those responsibilities and projects, assuming we’ll feel useful and validated when we’re done. And sure, we feel something most of the time.

But does our incremental gain in validation measure up to our desire? Does it stick around for more than 24 hours? Generally, no.

So the cycle repeats. We commit to more responsibilities and projects, because each one is a chance to eke out a little more validation. We follow through and, again, we’re disappointed or unsatisfied with the results.

So the cycle repeats again.

You get the idea.

The cycle often ends when we burn out. We get sick, become depressed, lash out, give in to impulsive or addictive behavior, etc.

The other way it often ends is when we get fed up with it and quit as many commitments as we can. We get frustrated. Maybe we feel like it’s time to pivot. We might look around and blame others for our exhaustion or chalk it up to it just being one of those “seasons of life.” And absolutely, any or all of those things can be true.

But I also know (personally and professionally) how likely it is that we’ll end up right back in the Validational Spiral. We repeat it over and over again—until the next burnout, the next breakdown, or the next burn-it-all-to-the-ground.

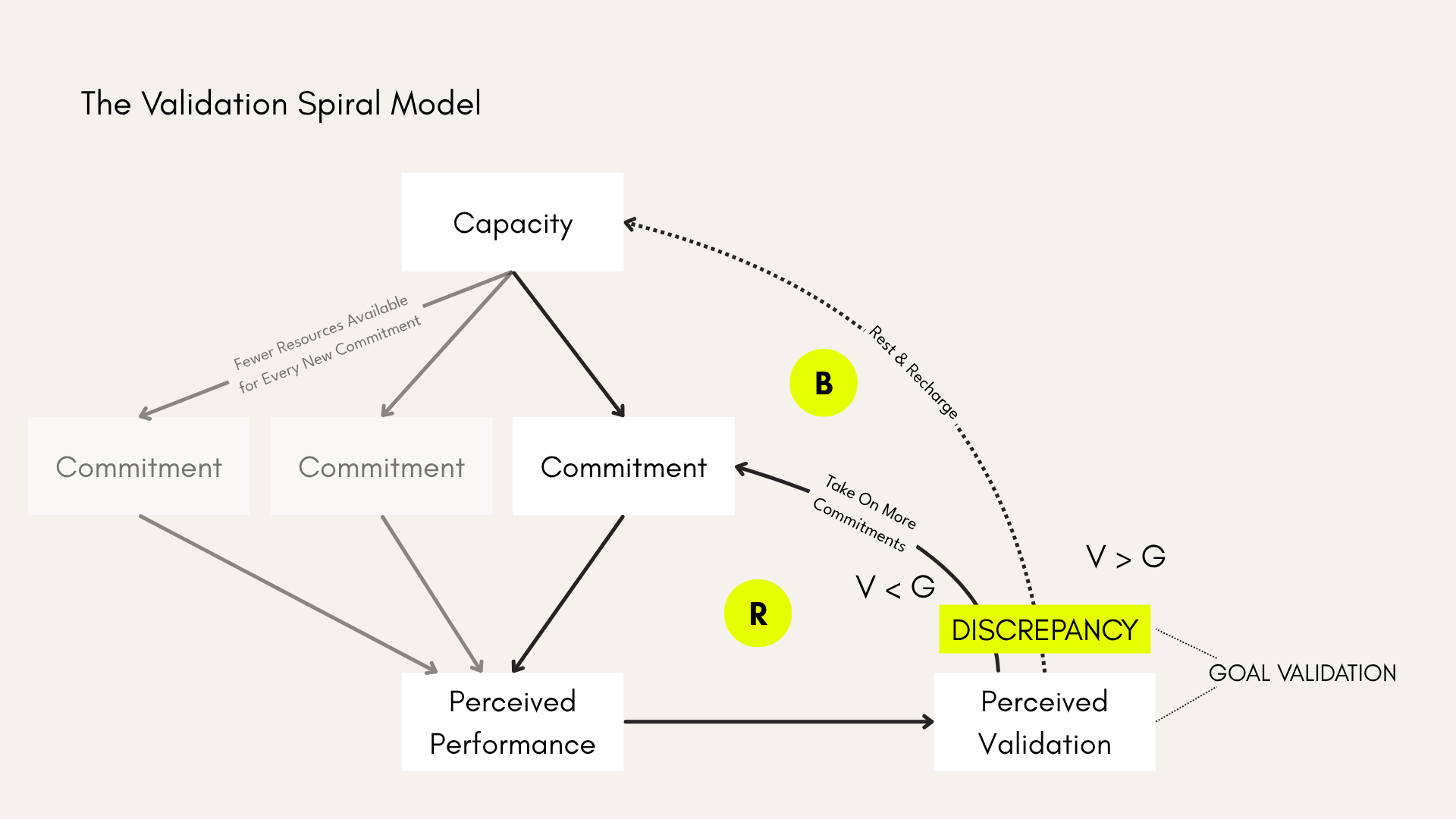

That recurring pattern of behavior indicates that a system is at play. Specifically, there’s a feedback loop. I called this system the Validation Spiral because I wanted to highlight the way it spirals out of control. A pattern of behavior that spirals out of control indicates that there’s a reinforcing feedback loop at work in the system.

Deconstructing the Feedback Loop

In this case, the reinforcing feedback loop leads to a situation in which we’re stretching our available resources thinner and thinner. We don’t have what we need to do everything we’re committed to well. All we have available for any given project or responsibility is enough for a mediocre performance. And since we’re not going to be satisfied with mediocrity, the lack of satisfaction brings us back around the loop and convinces us that this time it’s going to be different. This time, we’ll feel the validation we crave.

Systems tend to self-perpetuate. And the Validation Spiral is a perfect example. The reason systems self-perpetuate is that their structure, rather than the composition of their elements or the rate of their flows, dictates their behavior. Real change typically requires altering the system's structure to break the pattern.

So let’s examine the structure of the Validation Spiral.

I see the Validation Spiral as two feedback loops—one balancing and one reinforcing. Only the balancing loop is merely theoretical. In practice, it never gets to do its job.

So theoretically, the balancing loop allocates my capacity or resources to my commitments. I follow through, examine the results, and feel a sense of usefulness and validation based on my perceived performance. Again, theoretically, when I perform well, I reinvest in my capacity with some time off or a good night’s sleep, and start the loop over again with a full complement of resources.

Theoretically.

In practice, my performance is never enough. Mediocrity wins. I consistently fall short of my expectations, and my level of validation is always lower than desired. Instead of recharging, I double down. I hit up the next round of projects and responsibilities with depleted capacity. This is the reinforcing feedback loop. As my commitments increase, my performance decreases while my sense of validation fades. The cycle continues until I’m totally out of fuel.

That’s the tipping point. When we’re so stretched thing we can’t make another trip through the loop, we decide to make a big change. That’s when we burn it all to the ground or make a career change or rebrand or end a relationship. We assume that changing what we’re committed to will break the cycle. But it won’t.

Given time, the loop prevails.

The only way to break the cycle is by changing its structure. The key to rewiring the Validation Spiral is decoupling perceived performance and validation. As long as the goal of my feedback loop revolves around asking whether my results are good enough to justify feeling that I am good enough, the system will produce the same results.

And I know, I know. We’ve been there, done that, right? We’re all self-validating, self-affirming, self-supporting people who would never get caught back in this loop.

Yeah, me neither. And there are systemic reasons for that, too. I’ll get there in a minute.

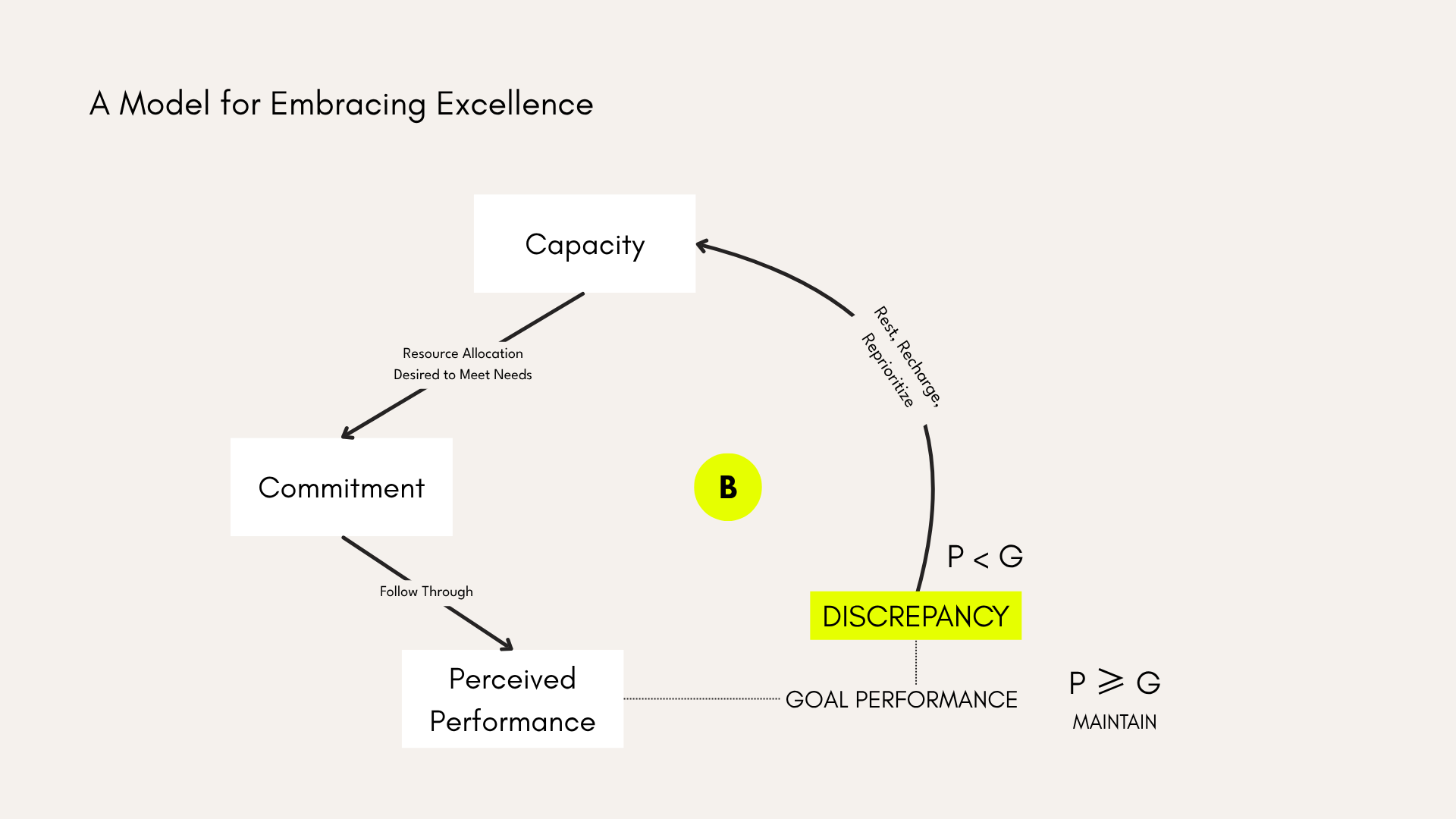

However, first, let’s examine what a truly balanced feedback loop could look like. It’s almost identical to our reinforcing loop. But there are two critical differences: (1) validation is not part of the loop at all, and (2) the trigger for recharging isn’t high performance, it’s low performance.

The loop still uses performance as a critical indicator. But the goal is no longer to feel valid based on performance. Instead, the goal is based on objective(ish) standards for performance. For example, I set a goal to execute a new bread recipe rather than (subconsciously) setting a goal to feel like a good bread baker. Or I set a goal to run a half-marathon rather than setting a goal to feel like a well-trained endurance athlete. The former are performance-based goals, and the latter are validation-seeking identity-based goals.

In the first example, if I fail to produce a tasty loaf of bread, I’m not jeopardizing my identity and looking for ways to reclaim it. Instead, I can assess what went wrong and regroup. Maybe I needed some higher-quality ingredients, so I run to the store. Maybe I missed a step, so I realize that I need to take a break and try again when I’m better able to focus.

In the second example, if I fail to finish the half-marathon, I don’t need to doubt myself. I can investigate where I went wrong with my nutrition, training, rest, race plan, etc. I can regroup and try again in a few months.

I can be dissatisfied with my results without being dissatisfied with myself. I can accept failure or poor performance without the internal experience of mediocrity and insufficiency. And from that acceptance, I can reevaluate my capacity, reallocate my resources, and reprioritize my commitments to increase my chances of success in the future. Success, I should clarify, that isn’t a condition of my own satisfaction.

Of course, breaking the connection between validation and performance is like trying to swim upstream. We can do it, but it requires effort and attention. It’s not a single decision we make. It’s a repeated commitment to affirming ourselves and, as Lorde put it, embracing excellence.

Embracing excellence transforms the structure of the feedback loop. Validation and satisfaction are no longer the hinge point of the system. Validation and satisfaction—the embrace of excellence—are the system. My validity and satisfaction, my enoughness, are the source of my power. Without them, I don’t have what I need to follow through.

To pursue excellence, I must acknowledge that my validity and satisfaction are preconditions for performance rather than the result of it.

There are material limits on the work we turn down and the responsibilities we shed. I may not have the resources to embrace excellence in everything my circumstances require of me. I may very well have to accept mediocrity in some (or even many) things. But I don’t have to let that mediocrity change who I know myself to be. I can choose when to accept mediocrity and find small ways to pursue excellence and experience satisfaction as I can.

Melissa Febos, speaking about her latest book The Dry Season, shared a bit of wisdom from her therapist: “You can’t get enough of a thing you don’t need. It’s just endless hunger.” We don’t need the things we think will earn us validation, valuation, or usefulness. Doing more of them won’t sate the hunger.

Mediocrity starves us of excellence and satisfaction. So we must change the conditions that find us always sitting at its table. We have to forget our “fear [of] the yes within ourselves,” as Lorde puts it. “When we begin to live from within outward,” she continues, “…allowing that power to inform and illuminate our actions upon the world around us, then we begin to be responsible to ourselves in the deepest sense.”

Whenever I talk about the Validation Spiral or pursuing the satisfaction of a “job” well done, I am talking about something practical—tactical, even. Deconstructing that reinforcing feedback loop will prompt you to reprioritize and reallocate resources. You have to say “no,” if you can. You have to quit, if you can.

However, those practical changes are in service of the kind of deep, spiritual yes that Lorde writes about. They’re the keys to power and knowledge. The practical changes can’t last without the scaffolding of belief that makes them possible. The reverse is also true. Changing our belief in the need for external validation or evidence of our usefulness requires the scaffolding of practical change.

It’s a system, and we make it real every time we choose excellence over mediocrity.

I often think about my construction paper amusement park—the focus, the pleasure, the satisfaction. It’s how I measure my commitment to excellence and how I remember what I’m capable of. I wasn’t just building rollercoasters and a carousel; I was building a scaffolding of satisfaction.

Footnote

Astute readers might notice that I’m drawing on Audre Lorde’s “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” but I avoided the word “erotic” in this essay. I didn’t do that because I think it’s a bad word (or worse, a bad idea). I love that essay—but on balance, I made the choice to use more familiar language and save readers from my clarification of the term.