Work Doesn't Have to Make Money to be Valuable

On a typical evening, you’ll find my husband, Sean, and I on the sofa. We eat dinner and crack up watching the latest Good Mythical Morning episode. After, we move on to whatever television show we’re binging–currently The 100.

I work on a crossword puzzle or sketch. Sean dons a thimble and gets back to work on the quilt he’s making.

When he’s not running our production company, Sean is the quintessential renaissance man. He knits; he quilts; he builds things; he paints; he pickles; he makes kombucha. Look, I’m not trying to brag–it’s just that he’s kind of amazing. Coincidentally, our fourth wedding anniversary was on Tuesday.

On our first date, Sean told me about a website idea he had: The Beer In Between. It would be a place to share reviews and travel writing about craft beer brewed in the heart of the American west–Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and the Dakotas. I told him straight away that he could make money on the venture. He was less interested in making money and more interested in the idea.

But I didn’t realize that then. At that time, I still perceived every idea or hobby with a you-can-monetize-that! mindset.

Nevertheless, I showed him how to purchase the domain name on a subsequent date. If that’s not a Millennial love story, I don’t know what is. I’m sure he’d want me to point out that he is actually Gen X.

We never built The Beer Inbetween. Nor did we build out any of the other ideas we came up with–that is, until we launched YellowHouse.Media. Sean has always been very wary of getting paid to do things he’d be doing anyhow. He’s cautious about “loving” the work that constitutes his livelihood.

So when I decided I wanted to create a companion piece to the one I did on “getting paid,” I knew I needed to talk to Sean. Initially, I envisioned the companion piece unpacking the history and theory that shapes our perception of leisure and hobbies. But instead, Sean’s perspective was rich enough that I think it stands on its own.

Sean has a unique perspective on work and leisure thanks to his family’s Mormon pioneer roots, his time spent in an Iñupiat village in rural Alaska, and a haphazard hippie early adulthood. He’s owned property cooperatively, worked in a co-op bakery, and spent plenty of years in the service industry working for tips. Even as he’s grown as a business owner and employer, he’s maintained a work-to-live rather than live-to-work attitude.

The following interview has been edited for clarity.

Tara: How did your family influence the projects you value today?

Sean: In one way or another, quilting has always been in my life. My grandmother was a really important person in my life. And she quilted constantly. It had to be utilitarian. It was pretty, but not so pretty. It was always like, “Oh, I've got these scraps around. I have to do something with 'em.” She involved me in quilting with her at a young age. She would just have me sit with her. And it was so funny because my stitches were so bad.

In my family, we almost always fill leisure and downtime with something productive. When people would get together, it was to make jam or to quilt. Gatherings were about crafts and stocking up–that type of thing. And I would say that I have certainly picked up on that. Not in like a survivalist paranoia type of way. I have so many memories of the pleasure of gathering together to take care of something as a family–to pick and can a bunch of cherries, for example. We were way more likely to go out and pick our own fruit at a local orchard than to buy it.

My grandma would say, “What do you want for dessert? Go down into the pantry and find something.” And I’d walk into a room where there was a year's worth of canned goods she had made herself on the shelf.

My grandmother and most of my extended family are Mormon, even though my immediate family isn’t. Mormons are pilgrims–that’s the narrative they tell themselves. Mormons have a real kind of homesteader vibe to them. A lot of self-sufficiency–stocking your pantry, learning hand skills. Independence is a big thing. It’s pretty fundamental culturally.

That said, I also give the caveat that when I talk about Mormon culture, I’m talking about my family culture. I know of Mormon culture strictly through that experience rather than direct knowledge of the church and its teaching. Although I certainly have some of that, too.

What you learned growing up between Utah and Montana was not what I learned in the suburbs of Pennsylvania. That’s for sure! One of the biggest lessons you learned via your family culture was that all time is equally suitable for paid work as it is for making a home, connecting with family, and finding pleasure in craft. That just isn’t the ethos I grew up in. Tell me about your move to rural Alaska when you were about 13.

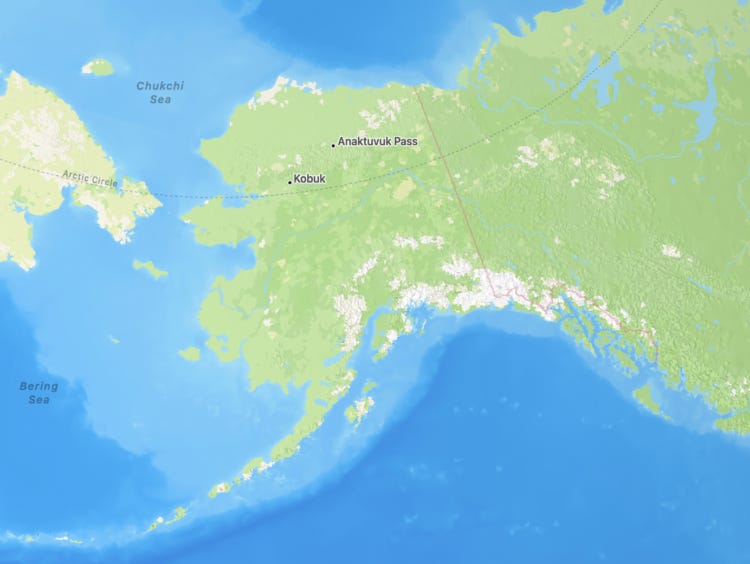

I lived in a village of about 100 Iñupiat villagers. The area isn’t connected to other towns by a highway or road. So you had to fly in on a bush plane to a gravel airstrip. Kobuk, the village, was on the bend in a river. It’s just a tiny little place. All the houses were built up on stilts because every spring, the ice on the river would break up, and the river would flood the town. Everyone prepared for it; it was fun to be in the village.

There was a jade mine 5 or 10 miles out of town up in the foothills of the Brooks Range. A road went up there, so there were a few trucks in town. People did drive up there in the summertime. But in the wintertime, we used snowmobiles exclusively to get around.

And it was freaking cold. It was above the Arctic circle.

There wasn't any running water. And so, there was like a central spot where everyone would go to get water. There were showers there, too. All the people there were subsistence hunters and fishers. There was no grocery store; there was no place where you could go and buy the basics.

If you wanted something that you didn't have, you made it. And, it was a pleasure. People took pride in the mukluks, parkas, and nets for fishing that they crafted from the resources around them. It wasn't a big deal. It was just what you did.

Between what I learned from my family and my experience in Alaska, I became who I am today.

Your step-dad was one of two teachers in the village. There were almost no other white people. Today, you and I have a much better understanding of the socio-political implications of that dynamic. But what was your relationship like with others in the village?

I would say with relative confidence that most people who lived there would still invite me in. But we were outsiders. People knew we weren’t there for the long-term.

So, there are many ways that we never fully integrated the subsistence hunting and fishing lifestyle. But that didn't mean that when the end of the school day came, I didn't go out fishing with my friends.

The only meat we ate was caribou and moose. There was a time in my life when, if I ever had to look at caribou or moose on my plate ever again, I’d just scream! We also said, “Do we have enough meat for this year?” And we made sure that we did, and we did it with other people in the village.

My little buddies and I would go fishing. We'd catch way too many fish. And then we’d take a garbage bag (because that's all we had to carry stuff in) and fill it up. We’d go around to all the little old elders–the aanas [short for the Iñupiaq word for grandmother], as they say “up there.”

We’d say, “Aana May, do you want some fish?” And they're like, Again? And the only way that they would take them from us was if we cleaned them first. So we always did that.

You’re always quick to note that there’s nothing romantic life in the Arctic. It was hard living. And still, you have many beautiful and formative memories. Tell us your snowshoeing story.

I had some snowshoes–the kind for deep snow, nearly as long as I am tall. So I'd go out in the winter with my rifle. I’d shoot ptarmigan and rabbits and things. Those small animals would augment what we were eating. Ptarmigan, by the way, taste terrible. There's nothing to them.

Mostly, I would just get out of the village because there weren’t a lot of kids my age. I spent a lot of time alone.

One day, there was some fresh snow. It was lovely. So I went out, and after a bit, I came across someone else's snowshoe tracks. And so, you know, I fell in behind to see who it was. And it was Taata Joseph. [Taata (taataruaġa) is grandpa in Iñupiaq.]

Joseph spoke almost no English, and I spoke almost no Iñupiaq. But, we spent an afternoon together. He was girdling trees. That’s when you cut the bark around the base of a tree to kill it. And then, you wait like a year for the tree to die and the wood to dry out. Then you only have to deal with lighter dry wood as you cut the tree down and process it. Because moving and processing green wood is miserable. He had an ax, and I was the young guy. So he made me do all the work. We spent the afternoon together.

It was fabulous.

I know you learned a set of values that we don’t often learn in white American culture. How did living in Alaska shape your perception of a valuable life?

I was talking to a client about how we value ourselves. So often, it’s all about our positions, our careers. You know, we can't respect ourselves if we aren't moving up the corporate ladder. Nor is anyone else going to respect you.

In Kobuk, the most respected people in the village had never had a job and never would. They’d never had a bank account and never would. Maybe they have some money stashed away somewhere. But village life just didn’t revolve around jobs. Five people in the village might have a job–maybe at the city office, the post office, or the school.

And so, what did people do with their time? They took care of shit. Meaning, you were getting caribou. You were fishing year-round–checking the fish traps, spending time at fish camps, smoking what they caught so they’d last. You’d take a boat up the river with your rifle and shoot beavers and small game. You’d use what you hunted, making the trim of your parka with some beaver fur, for example. You were making sure your house wasn’t falling apart.

It was not idyllic. There were suicides and alcohol issues.

But there was also a lot of joy. There was a lot of time sitting around playing cards. There were whole village cribbage tournaments!

Let’s shift gears a bit. I know you’ve been clear from the get-go that your business will not be your life or your identity. Your business doesn’t hold some hallowed place in your heart or on your calendar. So how do you identify today?

I'm a creative. And I'm an artist–fiber art, drawing, painting, playing my guitar, or whatever it is. That's what I am. And I believe that, in some capacity, that's who I will always be.

The art and the creativity will never go away. The work–the job–is transient. What I do now is only temporary. I don't know how long that's going to be. I mean, it could be another 20 years! My employment subsidizes my true identity, which is artist and creative.

My business is there to ensure I have a place to live and provide what I need. But it’s not my identity. Whether it’s this business or any of my previous jobs, I try my hardest to find a thing that isn't distasteful to me. And even better, something that I actually on it, at least part of the time, really enjoy.

I think that does differentiate my view towards work. It seems to be a different view than a lot of people have.

Yeah, I get the impression that you spend little to no time thinking about how to grow the business or make more money. You don’t think a lot about bringing on a bunch of new clients. The company could become much larger and generate a lot more revenue–but you’ve been very intentional about keeping its capacity at a certain level, at least for now. We’ve essentially traded a smaller profit margin for the privilege of paying a few outstanding, talented people to work with us and reducing the time you have to spend working. So what does that mean for the way you structure your day?

In the past, I’ve experimented with compartmentalizing things. You know, this half of the day is dedicated to this, and the other half is dedicated to that. But that means that the things I want to do always get pushed back and become secondary.

I never get around to the projects that are truly important to me. Or by the time I do, I'm too tired to have any interest in it.

Also, my creativity strikes at very unpredictable times. I can set aside time to say I'm going to work on a project. And sure, I can sit down and probably get things going. But it’s a struggle. So, what I’ve done instead is to arrange my room–my studio and office–so that I can access what I need when inspiration strikes.

I have a desk almost exclusively for paid work in one area of the room. It's where my computer, mic, and extra monitor sit. And then, in reaching distance from me, is my work table where I basically do everything else. My various materials and media are stacked or shelved around that table. If you were to walk into my room and look at my work table, you’d see whatever creative project I’ve got going on. It’s there so that I can do creative output in short spurts. I'll do 15 minutes here and there. I have a sketchbook at my desk so that if I'm, say, waiting for something to download, I will do some sketching.

I used to try to establish more conventional boundaries. And while boundaries do exist, they exist elsewhere. I’m comfortable enough with my project management and workload at YellowHouse that I can switch back and forth without losing track of deadlines or deliverables.

In the long view, though, I know I can't wait for time to appear to do the things I want to do. I have landed on just making it all the time. I always incorporate an artistic perspective in what I do.

It’s worth noting, of course, that we aren’t custodial parents. And we live in a relatively inexpensive locale. Many people can’t allocate their time as you do, but I still think there’s something valuable in thinking through the flexibility you create between your work and your art.

So, I’m going to put you on the spot. Why haven’t you pursued turning your art into a business?

I harbor quiet aspirations about turning art into something I can live off of. I think that would be wonderful. I just don't know how to go about that, you know?

Woah, woah, woah. But you do know how to go about that…

Do I?

I guess I could probably figure it out. Wait, what am I talking about? I could probably figure it out. I know I could figure it out.

But you also have access to an incredible wealth of resources.

When I say I could figure it out, that's what I mean. I have you. I have so many relationships with people that make their living through art. They would share what they knew with me and be so psyched to help me achieve that.

So why don't you then? One of the big questions that I'm interested in with this piece is: Why do we decide to try to make money off of a talent, interest, or skill? Or why do we choose not to?

With your visual art, you know quite a bit about how to turn that into a business. You do have aspirations of becoming a working artist. What's stopping you right now? Or what is going into the thought process behind not setting up a shop and calling it a side hustle?

I talk about subsistence work and this idyllic village where people never have jobs. I talk about it as if I am above and separate from the pressures that our society puts on people. I also have that internal voice that will criticize me if I do something that doesn't have value. That, for whatever reason, is of less value and is not worth doing. Some family voices say, “Art isn't worth your time.”

And I remember right at the very moment where I stopped drawing. It was in the fourth grade. A teacher teased me, and I stopped. Up to that point, it was all that I did. It was a big part of my daily life; I just drew. So, I am not immune to those pressures, those voices in our society that say that there's a thing that you do that is worth doing. And other things that are not.

Okay, I’m not sure you truly answered that question! But I appreciate your honesty. We’ll keep working on that one. As we wrap up, I’d love to hear about the similarities in how you approach art and business. I know one doesn’t serve the other–but they seem connected in craft and process.

I like slow craft. Process is fundamental to me. When I set out to make a piece– whether that's a drawing or painting or performance or whatever–the process is significantly important to me. And one of the reasons I like to work in arts and crafts is that they’re so tactile.

I've realized that physicality is essential. The more I can engage with either my work or my art in that more tactical way, the better.

Now Sean’s experience, of course, isn’t advice. His process or framework for approaching how he uses his time or decides what work means to him isn’t supposed to be a blueprint for others to copy. There are plenty of ways Sean works that just aren’t logistically feasible for most people.

My hope is that hearing how someone else explores the relationship between paid work and every other valuable kind of way to spend one's time will encourage you to rethink some of your own assumptions.

For more on life in rural Alaska and how colonialism, capitalism, and socialism have shaped the lives of the people and animals who live there, I encourage you to check out Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Sea, by Bathsheba Demuth.

For more on the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (1971) and the corporation system, visit the ANCSA Regional Association website.

And for more on the Iñupiaq language, click here.