"What do we want to preserve?"

Information overload is an ancient problem. I talk with Sari Azout, founder of Sublime, to learn how she approaches collecting and creating ideas in the post-information age.

Clients, students, and followers often ask me how I keep track of ideas and information. They want to know how articles and podcast episodes like this one come together.

I think they imagine I employ a sophisticated system of notetaking, an elaborate organizational structure that makes content creation effortless.

Orderly. Linear. Logical.

It’s no wonder. Between apps like Roam and Notion and books like Building a Second Brain and Digital Zettlekasten, personal knowledge management has become a popular hobby in certain niches. Aesthetically, I’m quite drawn to these apps and prescriptions for organization. I love the idea of having every note, quote, and concept in its place. I’m a sucker for new software, and I daydream about using any of these apps to their full capacity and making my work much easier.

But when clients, students, and followers ask me how I keep track of ideas and information, the answer I give is “piles.”

My notes, quotes, and concepts accumulate in messy little piles (or messy big piles, depending on the project). I take those piles and look for patterns. I rearrange and recombine.

Eventually, when things go well, I carve an outline or draft out of the raw material in my pile.

After explaining this to a group recently, someone replied that they loved finding out other people's systems are as haphazard as theirs.

I’ve often felt a bit embarrassed by my haphazard system.

There’s part of me that wonders whether I could do better work faster and more efficiently if I had a more robust system. Maybe. Maybe not. Is better work faster and more efficiently even a good goal to reach for?

The truth is that I’ve tried other systems. I’ve tried to standardize my notes or develop a regular routine for processing what I’ve read or listened to that day. Inevitably, I end up with piles again.

But a year ago, I started using a personal knowledge management tool that, in a way, encourages my pile technique. It’s called Sublime, and it’s the brainchild of

. When I spoke with her about Sublime a few weeks ago, she told me that she’s “on a quest to get more people to feel and understand the value of” curating a personal knowledge library.Sari is also a writer and thinker known for approaching technology, community, and business in ways that don’t acquiesce to the Silicon Valley status quo. Sari and the whole community at Sublime remind me that there are lots of people out there who care about rigorously collecting ideas and information without rigidly following a prescribed system.

Keep reading or listen on the What Works podcast.

The Post-Information Age

We’ve all heard the internet era described as the ‘Information Age.’ But recently, Sari framed things differently. We’ve now left the Information Age behind and entered the Post-Information Age. Accessing information is no longer an issue—it’s navigating, archiving, and making sense of all the information we have access to that’s the real challenge.

“We were operating in a world of scarcity,” she explained, “There was very little information. And we’ve been transitioning to a world where the opposite is true, where abundance is the biggest problem.” In a world of information abundance, the question isn’t ‘How can I learn what I want to learn?’ The question is, ‘What do I want to say? Do I have the courage to say it?’ She continued, “To me, so much of the shift from scarcity to abundance, from not having enough information to having too much information, is really about how we develop the courage and intention.”

It’s objectively true that there is more raw information in the world today than yesterday—let alone a hundred years ago. We know more about how the human body works, what the universe is made of, how ancient civilizations functioned, and why the summers keep getting hotter. It’s also true that more of us can access that information than ever. More of us also have time to think about and respond to that information, even if time is a scarce resource.

However, that doesn’t mean the problem of ‘too much information’ is new. It’s not.

Feeling like there’s too much information to remember, analyze, and respond to is an ancient problem.

So it’s time to historicize this drive to collect and curate a personal knowledge library.

Historian Ann Blair writes that:

...the perception of and complaints about overload are not unique to our period. Ancient, medieval, and early modern authors and authors working in non-Western contexts articulated similar concerns, notably about the overabundance of books and the frailty of human resources for mastering them (such as memory and time).

In Blair’s aptly titled book Too Much To Know, she traces information or knowledge management back through many different practices and reference types—including early dictionaries, bibliographies, library catalogs, and mixed reference books.

A 2nd-century Roman scholar named Aulus Gellius described his practice like so:

I used to jot down [annotabam] whatever took my fancy, of any and every kind, without any definite order or plan; and such notes I would lay away as an aid to the memory, like a kind of literary storehouse.1

Sounds like a pile to me!

One prominent example of this type of knowledge collection emerged in the Renaissance period.

It’s called a ‘commonplace book.’

The exact nature of a commonplace book is specific to the person creating it. But essentially, a commonplace book is a collection of notes, quotes, and concepts based on reading and observation.

Here’s how Sarah Mackenzie, an author and the founder of Read-Aloud Revival, described her own commonplacing practice:

A commonplace book is very simple. It's just a journal or a notebook where you're saving passages or words or quotes from a book you love.

My commonplace book is actually just in my notes app on my phone.

I just keep a notes app on my phone where I jot down a passage or a quote from a book that I really love. A lot of times, I use it on my phone. I also have a notebook that I sometimes write in. I'm just less likely to do that because I have to go find the notebook, and yada yada.

There's no right or wrong way to do [it].

Blair notes that as early as the 15th century, European humanists were explaining the value and importance of the commonplacing practice. By the early 17th century, Jesuit scholars Francesco Sacchini and Jeremias Drexel had written manuals on how to keep a commonplace book.

Given the description of a commonplace book thus far, you might imagine something that resembles a book of inspirational quotes. Something you might buy as a heartwarming gift for a recent graduate or new mom. A chotchke of a little book.

And commonplace books can indeed be a source of inspiration. But the real “magic,” as writer, podcaster, and media theorist Steven Johnson put it, is in the creative potential of commonplace books:

...all of this magic was predicated on one thing: that the words could be copied, re-arranged, put to surprising new uses in surprising new contexts. By stitching together passages written by multiple authors, without their explicit permission or consultation, some new awareness could take shape.

By virtue of their haphazardness and frequency of use, commonplace books encourage the spontaneous and unexpected juxtaposition of ideas that lead to new ideas.

I’m not the first to notice the connection between Sublime and commonplace books. Sublime user Keely Adler, who describes herself as a brand strategist by trade and time-traveling futurist at heart, put it this way:

it finally dawned on me, what exactly @sariazout has managed to do with @wwwsublimeapp. she went and built the digital, collaborative, commonplace book of my dreams

Our tools shape us

A commonplace book can be used in a variety of ways and for a variety of purposes. But they’re often used creatively—as a source of new ideas and insights that can be refined as articles, books, poetry, or other media.

Johnson notes:

The tradition of the commonplace book contains a central tension between order and chaos, between the desire for methodical arrangement, and the desire for surprising new links of association.

My own resistance to elaborate personal knowledge management systems is a resistance to a process designed to smooth out that tension. Or, I’d like to think that’s what’s going on. Research is a leisure activity—a way of life. Allowing for chaos, for the disorganized piles of ideas and information strewn around my digital home, leaves room for discovery and creativity. Eliminating that chaos threatens to eliminate the potential for discovery. Or, so I tell myself as I excuse my mess.

Sari told me that she often thinks about the idea that “We shape our tools and our tools shape us,” a paraphrase of one of the central ideas of Marshall McLuhan’s work.

We shape our tools to eliminate chaos. We want things to be neat and tidy. And really, software needs things to be neat and tidy. Despite what some claim, even the most sophisticated AI systems can’t deal with chaos.

Our tools require standardized formats and predictable inputs. Even something like ChatGPT, which claims to allow for “natural” language processing, works best when prompted in ways that take advantage of the quirks of its model.

Because our tools then shape us, we learn how to navigate chaos-free environments. Or we try to. But the real world, the world not dictated by software features and algorithms, is, of course, full of chaos.

Translating chaotic reality into something algorithms can understand brings us marketing practices like search engine optimization. The basic premise of SEO has been to take messy human communication and make it legible to search engines. Use the right keywords, syntax, and tags, and you can generate steady traffic to a website.

Sari explained that the kind of information we come into contact with most often results from algorithms with limited abilities and coded with intents that don’t match ours. That is, we find it on search engines and social media platforms. “What you tend to see on Google is SEO optimized,” she told me, “Nobody goes to the second page of Google, so if the first page is all of the SEO manufactured stuff, then that’s a big part of where you’re getting your information.”

The software we call artificial intelligence uses our code-optimized content like a machine-readable commonplace book.

That’s what happens when Google spits out an answer to your question in its ‘AI Overview’ or when ChatGPT helps you with market research. Unfortunately, in the process, AI can ‘hallucinate’ poems by famous poets, court cases for legal briefs, and even how many Rs are in the word ‘strawberry.’

I don’t blame these systems for making mistakes. Anyone can make a mistake using a knowledge management system. The real problem is that we abandon critical and analytical thinking when we use these systems. Further, we abandon our role in the creative component of search. Instead of remaining open to connecting the dots of our research, we take the answers we’re given.

The tools shape us.

It’s not just search or chatbots that are shaping us. Social media platforms and their algorithms play a role, too. If you’ve spent any time on a social media platform (if you haven’t, call me), you know that, as Sari put it, “It’s the loud people trying to engineer every single word to please an algorithm, to go viral, to engineer attention” that end up being prominent sources of information (or disinformation as the case may be). And the incentives of the various platforms encourage that result.

Social media platforms incentivize the activity that generates the most data and maximizes users’ time on site. Those incentives then shape not only the content we create but also the way we think and process ideas. The tools shape us.

Arguably, the most interesting stuff happening online is happening off the big platforms.

The quiet, private digital spaces and the familiar, friendly group chats—that is where much of the cool stuff happens. It harkens back to old internet. But it also harkens back to commonplace books and salons.

“The thing that I became obsessed with,” Sari told me, “is how do we actually bring the sort of intentionality and focus and quality to the kinds of stuff that you’re doing when you’re preparing” to make something. Her goal with Sublime is to protect the “sanctity of that space.” That space I take to mean our mental spaces, our creative spaces, our collaborative spaces.

“There are certain times in my life when I don’t necessarily want an answer. I want a journey,” she said.

Engineering serendipity

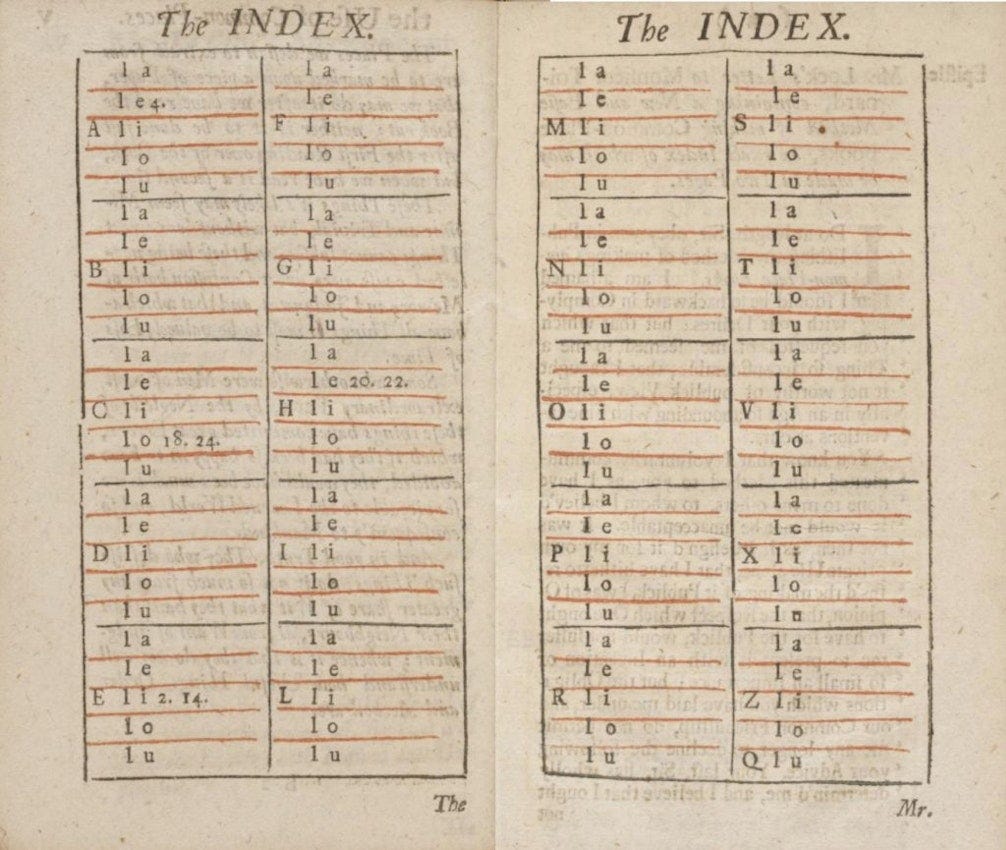

The 17th-century philosopher John Locke had a fascinating structure for his commonplace books. At the beginning of the book, there was an alphabetical index. Under each letter, Locke also wrote each vowel.

So under the letter B, there would also be the letter A, E, I, O, U. Same under C, D, E, etc.

When he happened upon a quote or idea that he wanted to put in his commonplace book, he thought up an appropriate heading for it. We might think of it as a category or a tag. For example, if I wanted to commonplace the quote “We shape our tools, and our tools shape us,” I might put that under the heading Media.

To place Media in my index using Locke’s system, I would find the M section and then select the first vowel in the word—so M-E. In the space for M-E, I’d write down the page in the book where I added the heading Media and placed that quote.

At first, you might think that’s an unnecessarily complicated system for a fairly imprecise result.

And in a way, you’d be right. However, this system provided just enough structure and organization to make Locke’s commonplace book something he wanted to use while also facilitating the journey that Sari mentioned. Yes, he might stumble on something unrelated to his question or concern using the index. But stumbling on something unrelated has its own value.

Is it inefficient? Maybe. In a sense. But it’s incredibly effective for producing the kind of serendipitous convergences that make for new insights.

When I asked Sari how her approach to personal knowledge management differs from many of the popular systems out there today, she told me it has to do with the purpose of the system. Most personal knowledge management systems and tools are built to increase productivity. She wanted Sublime to increase creativity.

“Obviously, there are personal knowledge management tools that are branded as ‘do more faster and more efficiently,” she explained. “Personally, I am more drawn to ‘make something wonderful.’ The ‘make something fast’ game is just one that we’re not going to win.”

While lots of software brands nod to our creative goals, the marketing copy makes it clear that it’s about moving faster, doing things cheaper, and producing more. Sublime seems to be walking its talk—which I find genuinely compelling and exciting.

What does it mean to build software to facilitate creativity rather than productivity? How does that purpose impact product decisions, organizational structure, and management practices? How does a focus on creativity change the user interface or customer experience of a product?

“I genuinely believe that we are reaching the tipping point on the returns of productivity,” Sari asserted. “The return on energy spent on creativity is going to be much higher than the return on energy spent on productivity.”

“Quantity is [AI’s] game, but quality and intention and taste have to be ours.”

Knowledge doesn’t grow in a vacuum

Commonplace books, like most personal knowledge management systems, are individual. They operate in what Sari calls “single-player mode.” And that’s great! Having personalized references helps us cut down on that feeling of overload that, as I mentioned at the top, is an ancient problem.

However, only so much engineered serendipity can happen in single-player mode. Knowledge can’t grow and evolve without exchange. Sari shared that she loves Voltaire’s idea of ‘cultivating your own garden.’ “In a world where there is just so, so much, you can’t do it all, but you can create your own little garden. You can have your own plot of land that you’re nurturing and going deep on and developing.”

The thing about gardens is that, at least in the world of this metaphor, they need pollinators. And pollinators don’t concern themselves with a single garden plot. Bees buzz from flower to flower without regard for fences or garden walls.

For centuries, ideas and knowledge were pollinated in institutions like universities and monasteries. As literacy spread, pollination also occurred around dinner tables and in smoked-filled salons. While these places still exist, ideally with far less smoke, our access to information is out of balance with our access to spaces where we can exchange, transform, and discover together.

Most people interested in ideas aren’t cooped up in ivory towers. They don’t retire to a monastic cell for contemplation after a long day of devoted service. We’re shaping our lives, relationships, and thinking with intention and curiosity—but we’re often disconnected from others who share our questions. We need a way to pollinate our gardens, too.

That’s the other piece that Sari wanted to incorporate into Sublime. It’s not social media in the way we’ve come to think of it—there are no likes or comments. But there are connections.

She envisions a ‘landing page’ of thoughts that show the work behind the work—the ideas that inspire essays like this—and can lead to new discoveries and inspire more creativity. With Sublime, I can go into my own personal reference, find something I clipped, and then discover five other relevant things people have clipped that I would have never found on my own.

“We’re not just making things,” she explained, “We’re making conversations, we’re making moments. How you live is an act of creation… and so much of that is driven by the ideas that you’re exposed to.”

What do you want to preserve?

Several years ago, Sari wrote a post that I still think about regularly. In it, she reflected on how we’ve developed a cultural and economic preference for disruption and wondered how things might be different if we asked, “What do we want to preserve?”

Part of preservation is, no doubt, the libraries, archives, and personal references we curate and compile. But another part of preservation, I think, is creative. It’s putting to use what we’ve saved, what we’ve deemed worth remembering.

Preservation is a promise to revisit and reengage.

Preservation is the hope of a future and its creative endeavors. And when we preserve together, preservation is a promise we make to each other.

I think it’s fitting to close with words I discovered on Sublime, the words of artist Corita Kent, whose own work was a radical preservation in promise to a future filled with love, justice, and life:

“Artists, poets, whatever you want to call those people whose job is ‘making’ take in the commonplace and are forever recognizing it as worthwhile.

I think I am always collecting in a way, walking down a street with my eyes open, looking through a magazine, viewing a movie, visiting a museum or grocery store.

Some of the things I collect are tangible and mount into piles of many layers and when the time comes to use those saved images I dig like an archaeologist and sometimes find what I want and sometimes don’t.”

Interesting in trying Sublime? Use my invite to get access! Or visit sublime.app for more information. You can also follow

on Substack. And you can follow me and Sari on Sublime!Quoted in Blair