Temporarily Embarrassed Millionaires and Loss Aversion

The American myth allows us to take possession of the dream of a successful life and then dares us to give it up. But there's hope in another way.

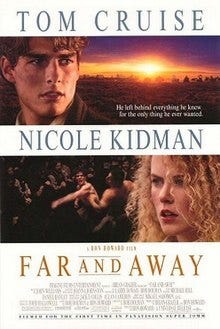

One of my favorite movies as a kid was Far and Away, starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman. It’s the story of two Irish immigrants, the tenant farmer Joseph (Cruise) and Shannon (Kidman), whose family is from the landowning class. They arrive in America, each with dreams of claiming a homestead in Oklahoma. Not pictured: the Cherokees whose land it was, just a few generations after the Trail of Tears.

Now, look, this is not a good movie. Here’s what Roger Ebert had to say about it:

“Far and Away is a movie that joins astonishing visual splendor with a story so simple-minded it seems intended for adolescents...”

But that “simple-minded” story is exactly why it’s on my mind. Joseph is the embodiment of the American mythos. He believes he’s destined for greatness, that America is where he can finally be free, and the ticket to his self-actualization is owning a plot of land out west. At the same time, Tom Cruise himself embodies another aspect of this same story. He is the quintessential American celebrity, handsome, full of swagger, ridiculously wealthy, and even does his own stunts. And all that after a rough childhood.

In Joseph, we find the stick-to-it, do-whatever-it-takes drive that is supposed to ensure our success in American meritocracy—while Cruise presents a glimpse of the future that awaits us.

The story takes place in the early 1890s—a heady time in American history.

The abundant resources of the American expanse provided robber barons with everything they needed to accumulate their fortunes. People like Carnegie, Morgan, and Rockefeller dominated the economic landscape. At the same time, immigrants poured in to work in their factories and on their railroads. Irish and Germans, then Italians and eastern Europeans, and plenty of Chinese (before Chinese immigration was dramatically curtailed by the explicitly racist Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882) provided the labor necessary to catapult American capitalism into a new age.

I guess the trouble was that we didn't have any self-admitted proletarians.

Everyone was a temporarily embarrassed capitalist.

— John Steinbeck, “A Primer on the 30s”

John Steinbeck would later write that “Everyone was a temporarily embarrassed capitalist.” Steinbeck was writing about the Great Depression, but Joseph certainly fits this bill, too. He fancies himself a rich man in wait. When he’s successful in the boxing ring, he starts to buy himself fine suits and hats—claiming that he didn’t need to worry about saving money because he’d just make more during the next fight. Joseph doesn’t see that he’s literally breaking his body on behalf of wealthy men just to dress the part.

At the risk of spoiling a 30-year-old movie, Joseph eventually loses—having made a grave mistake in his final match while coming to Shannon’s aid. He not only loses that night’s prize but everything he’s earned (and managed not to spend). He and Shannon are kicked out of the boarding house they’ve been living in. He was so close to his American dream, only to suffer the embarrassment of destitution.

Don’t worry. It’s a Ron Howard film. Joseph does eventually secure his plot of land in Oklahoma during the land rush and manages to win Shannon’s love while narrowly avoiding death at the hands of her more class-appropriate fiancé. There’s a reason adolescent me would avail herself of this movie every time it was on cable.

Far and Away has been on my mind because I’ve been thinking about loss aversion.

And the role of loss aversion in the American psyche.

Loss aversion is a concept from behavioral economics and psychology (and, by extension, marketing) that explains how we are more likely to overvalue something that we already possess—and therefore have a strong tendency to act in a way that avoids loss.

Researchers in 2002 studied this effect by way of pizza. They had one group build a pizza order from scratch—choosing a crust, sauce, cheese, and toppings to complete their order. Then, they had another group start with a completed pizza order and asked them to remove the ingredients they didn’t want. The results showed that giving the customer a suggestion of a pizza order (e.g., meat lovers) and asking them to scale it down led to a more expensive order.

Think about that the next time you order DoorDash.

Still in Ireland, Joseph saw himself as a landowning, successful man. Even through the difficulties he experienced reaching Oklahoma, he never lost that image of himself. He couldn’t scale down his dream—because he was already in possession of his homestead in his mind. As far as he was concerned, America had already given him his meat lovers pizza.

Such is the American myth.

We learn to take possession of a vision of the future in which we are stable, comfortable, and successful. We start to tell stories about “what we want to be when we grow up” as early as 3 or 4 years old. If we grow up on the higher rungs of the American ladder, we might see ourselves as doctors, lawyers, engineers, designers, or business owners. Even if we imagine a life as an actor or artist, we imagine the celebrity version of those vocations.

Our pizza might not be a wood-fired oven Neapolitan with the finest mozzarella, vine-ripened tomato sauce, and hand-picked basil, served alongside an expensive bottle of Lambrusco. But there is no way we’re giving up whatever pizza future we believe we’ve been given.

In my book, I write that our goals “represent a chance at a better life, a less challenging identity, even the hope of a sort of salvation. To give up goal-setting can feel like abandoning an imagined future self that has things a little easier.”

This is the loss aversion that keeps us striving, that keeps us from defying the status quo.

Even when we want to.

The American myth—the root of which hasn’t changed since the country’s founding—allows us to take possession of the dream of a successful life and then dares us to give it up.

It’s a psychopolitical “gotcha.”

But I find quite a bit of hope here. If once I was acting to avoid the loss of [a successful career, a profitable business, a dream home, etc.], I can instead act to build up exactly what I want and nothing more. To me, this is a more pro-social position from which to act. If I’m avoiding loss, then my instinct is to see everyone around me as a potential threat. But if I’m creating and maintaining instead, I learn to see others as doing the same for themselves. We’re teammates rather than competitors.

If I’m a “temporarily embarrassed millionaire,” as Steinbeck is often misquoted, then I’m constrained to whatever choices promise my return to grace. But if I can finally shed that identity, I achieve the freedom of “self-realization with others,” as Byung-Chul Han puts it. “Freedom is synonymous with a working community (i.e., a successful one).”

The promise of that successful working community is that a level of reliable comfort and stability is possible. It’s not a promise to rectify my temporarily embarrassed condition but to prove that I was never really embarrassed at all.