Kids at Work, Games as Labor, Content as Product, and the Surplus Elite

The news about "work" today is weird. How can it help us understand our own position as workers... and what the future may hold?

On Tuesday (April 18), the Iowa Senate passed a bill that would allow minors to work longer hours and in more jobs than is currently legal. Sixteen and 17-year-olds would be allowed to serve alcohol with their parents’ permission. Kids under 16 could work up to 6 hours a day and as late as 9 p.m. during the school year, while 16 and 17-year-olds could work as many hours as adults do.

In the original bill, employers would not have to extend worker’s compensation coverage to minors—meaning teens wouldn’t have financial resources if they were hurt on the job. Democrats pressed for additional worker’s compensation for injured teens but only accomplished the extension of current worker’s compensation protections on the bill that passed (no Democrats voted for the bill).

Meanwhile, several other states, including Arkansas and Missouri, are considering or have passed similar rollbacks.

Legislators claim the motivation behind these bills is to expand opportunities for teenagers to gain job experience. But one thing is clear: kids are willing to work in jobs that don’t support an independent adult. And that means employers—with the help of state governments—are clawing back the small amount of leverage that workers gained over the last few years.

In The Column and in the Citations Needed podcast,

explains:“What we have, as several economists have explained over and over again over the past two years, is a shortage of adequate pay, a “shortage” of good jobs. What we have is organs of capital—trade and industry groups, Chambers of Commerce, pro-industry think tanks—running to the media and complaining about a ‘labor shortage’ as part of a two-year-long strategy to suppress workers’ wages and gut pandemic-related aid programs like enhanced unemployment benefits, stimulus checks, SNAP extensions, eviction moratoriums, and, now, child labor protections.”

My husband is newly obsessed with Duolingo. He declared that this would be the year he finally learns Spanish. And now, I often find him with one wireless headphone in his ear, staring into his phone. He says he is learning Spanish, but he’s also really enjoying racking up the points and maintaining first place in his league.

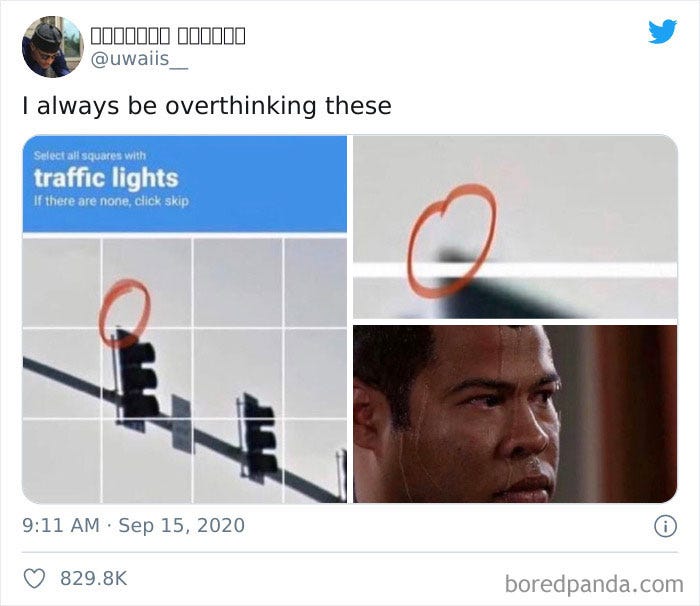

Saturday morning, when I sat down next to him on the sofa, he shoved The New Yorker my way (as he often does) and told me about the profile of Duolingo’s founder, Luis von Ahn, inside. Then, he told me that the founder of Duolingo is also the person who invented captchas and founded reCAPTCHA. As soon as he mentioned that, I knew where he was headed.

“Whenever we click on those photos to prove we’re human,” he said, still clearly in disbelief, “we’re training machines how to recognize things!”

“Yep,” I responded.

“You knew that already?” he asked. I sure did. I told him I didn’t know that the Duolingo guy was also the reCAPTCHA guy, but that it didn’t surprise me there was an element of free labor going on in the backstory of Duolingo, too.

Consumption is refigured as production.

All so that production can be, in theory, freed from human labor with all its needs and expenses.

Reddit, last week, announced that it would begin charging large language models (i.e., the programming that powers how AI systems like ChatGPT “learn”) to use its API. Reddit content, it turns out, has been one of the chief sources of the massive data sets that LLMs require to get better at learning how humans talk to each other.

All of that content, of course, is created by Reddit’s users—not Reddit. But once published on its platform, that content is “data” that can be bought and sold. We’re used to seeing this happen indirectly. Content and our responses to it are actions that indicate our preferences and enable platforms to sort us into audiences. Advertisers can then select those audiences when they purchase ads from the platforms.

But this change at Reddit shows a much more direct sale of the content we create. It proves that what we produce isn’t only valuable in terms of our susceptibility to advertising but as content itself.

The machines, it turns out, need us. Much more than we need them.

By turning the product of our time and energy into a product with exchange value, Reddit (and most other platforms) hide our labor and pocket the cash.

While these 3 stories might seem, at best, loosely related, they’re part of a longstanding trend when it comes to work. That trend is the continual deskilling of jobs to lower costs and increase profits.

Deskilling happens in a variety of ways and at a variety of intensities.

Machines and computers do make it easier to do some jobs—so less experience and training is required. Taylorist and Fordist management render skilled craft into tasks that can be done repetitively with minimal instruction.

Deskilling isn’t always a process of changing a job so that it requires less skill.

It’s often a process of changing who does a job and for how much money, giving the job the perception that it requires less skill. Allowing women and children to do jobs makes those jobs appear less skilled and, therefore, cheaper. Race, of course, plays a massive role in deskilling—as does, relatedly, the welfare-industrial complex and the prison-industrial complex.

These strategies take advantage of what Marx called “surplus population.”

Surplus populations serve two purposes.

First, they act as a release valve on any pressure labor begins to exert on capital. An employer doesn’t need to pay more or provide safer working conditions so long as there is a “reserve army” waiting to take the jobs that pickier workers leave. Second, surplus populations act as a source of value in and of themselves. They constitute informal economies that perpetuate systems that benefit capital, doing labor for little or no pay (housework, caregiving, content creation, running errands, etc.). Put a pin in that one, we’re coming back to it.

In his book Work Without the Worker, Phil Jones examines how platform companies like Facebook and Amazon make use of surplus populations to provide training for and bridge gaps in algorithms and “artificial intelligence” systems. What appears to be the “magic” of the algorithm is often a human—many humans—completing the work. Content moderation, image labeling, and improving search results are tasks completed for pennies (if compensated at all) by refugees, prisoners, and a growing number of workers forced out of their professions by technological progress.

The economic and political situation we allow these microworkers to live in is dire. Jones’ description of the work conditions, processes, and policies is disturbing.

And, I see echoes of this much closer to home.

Surplus populations are all around us.

When conservative politicians or frustrated small business owners say, “No one wants to work anymore,” and complain of a labor shortage, they don’t have in mind college-educated, ostensibly middle-class people. They mean the groups of people who have historically been willing to work for low wages in insecure jobs out of necessity. But as Johnson points out, we don’t have a labor shortage—we have a shortage of good jobs (i.e., jobs for which the compensation provides a modicum of financial independence and stability.

We also have an abundance of economic messaging that sells a college education as the key to attaining a good job. However, according to a survey by ResumeBuilder.com, 34% of recent college graduates work in jobs they could have gotten without a degree. Further, 40% of recent graduates have lowered their salary expectations since entering the job market.

We might think of that 34-40% of college graduates as being their own sort of surplus population.

They work in jobs that could otherwise be done by people without degrees. This can create some upward pressure on jobs in the retail, food service, and hospitality sectors—essentially acting as perceptual “upskilling” and squeezing non-college-educated workers out of the jobs they historically relied on. But that reserve army of college graduates certainly acts as a significant counterweight to any demands from professionals who are working in the fields they trained for. After all, an employer is unlikely to increase your paid time-off or raise your salary if they can pop into the local Starbucks and find someone with all the same educational credentials to replace you.

But this surplus population is increasingly employed in another way.

Or, rather, they are self-employed in another way.

They make up an expanding informal service economy, trading back and forth with others in a similar boat rather than engaging with the formal economy. Jones explains:

“Those left behind are forced to fill the roles of—or otherwise invent—a seemingly never-ending range of new and esoteric services, colonising an ever wider range of human activities: think hired friends and pet babysitters. In this sense, the term ‘services’ is perhaps a misnomer, hardly capturing the veritable cornucopia of miseries a stagnant system has in store for workers.”

We’re Substack writers subscribing to other Substack writers, creators patronizing other creators, online educators building courses for other online educators, coaches coaching coaches, or healers healing other healers. Even when we’re not passing our income around between workers in similar roles to ours, we’re spending money on coping mechanisms, conveniences, and experiences in this informal economy.

Many of us in this surplus population make do in ways that are not all that dissimilar to the microworkers of Mechanical Turk—even if we do so to support superficially middle-class lives rather than for sheer subsistence.

We might think of ourselves as a “surplus elite…”

…convinced to “choose” self-employment to hide the ways in which we’ve been pushed out of traditional labor relations.

I don’t want to minimize the plight of the microworkers that Jones describes in his book in any way. But I do think it’s worth examining the similarities between the challenges we face, even if the difference in the magnitude of those challenges is vast.

When we recognize our similarities, we can see paths forward.

Jones does offer an unexpectedly optimistic postscript. He proposes that, after examining microwork and all its exploitative excess, we might see the overall structure of microwork as a way to divide and conquer when it comes to the necessary work of society. Jones writes:

“In a wage society, working for twenty requesters over the course of a day and occupying as many roles in the economy does not, it turns out, offer independence and dynamism, just a dull, relentless struggle for survival. But in a post-scarcity world, where the wage and the associated division of labour have vanished, there is no reason why the small amount of work required could not be as various as the worker’s interests.

…

Indeed, a wageless society would still require people trained in a particular vocation, but this would neither be their only role nor their primary daily activity, but one of many. One might work as a medic for a few hours one morning and as a farmer the next, and in the afternoons write a novel. There would be enough people trained as medics to make sure that no one person had to perform the role at the expense of a rich and meaningful existence.”

This is a massive rethinking of society and our relations within it, to be sure.

But I find it an intriguing thought experiment. Would I, say, run a street sweeper for a couple of hours per day if it meant that I didn’t need to solicit paying subscribers ever again? Yes, I think I would. Would I deliver the mail twice a week if it meant that I could study philosophy without worrying about what I would do with another degree? Definitely.

Even more important than what I’d be willing to do for those privileges is the potential to unleash a whole class of people who rarely get to participate in creative, political, or social endeavors. What would I be willing to do so that others could do what I do (or whatever they want!) today?

When it comes to imagining the future, I don’t think it’s helpful to consider what is and what isn’t realistic. But if you want to say Jones’ proposal is unrealistic, be my guest. If “unrealistic” means something other than our actually existing systems, I’m all for it.

Designing an Audio Course

On May 11, I’m teaching a 1-day workshop through YellowHouse.Media on designing an audio course, and there are just 5 spots remaining.

I’ll walk you through how I think about instructional design, how I create a compelling package that goes beyond audio, and how to select your tech. By the end, you’ll have a complete plan for your audio (or audio hybrid) course. I hope you’ll join me!