Discover more from What Works

How We Talk About Work Matters

What we don't talk about when we talk about work requirements for public assistance.

The way we talk about work matters.

Discourse shapes public opinion—and with it, prevailing attitudes about how we work and what we expect from ourselves as workers. That's why I've been following the renewed debate about work requirements for public assistance related to the proposals to lift the debt ceiling in the United States. Admittedly, this isn't a topic strictly in my wheelhouse.1

Although I have written about something similar before:

But the way I see it is that we all work in the same labor market.

We all participate in the same culture of work. Talk—especially among powerful people in prominent media outlets—about jobs, workers, responsibility, and work ethic influences how we relate to work. It impacts everyone who works for a living, from the low-end to the high-end of the income spectrum—which is not to conflate the problems low-wage workers face with those high-wage workers face.

Sure, there are regional and class differences—but at the end of the day, the winds of American work culture all blow in one direction.

The rhetoric around work requirements for public assistance changes how we all relate to work by endorsing both exploitative labor relations and a socio-political hierarchy that sets us against each other.2

What are work requirements for public assistance?

The 1996 welfare reform bill (officially known as the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act) put certain requirements in place to quality for cash welfare. It created the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (TANF). The program requires most recipients to work 80 hours per month (20 hours per week)—paid, unpaid, or in exchange for goods or services. Alternatively, participants may complete"work activities," which can include job training or volunteer work. Workers must complete the necessary documentation to maintain eligibility. The debt ceiling deal currently being considered by Congress very modestly expands work requirements for SNAP (food stamps) for"no obviously discernible reason."

For almost 30 years, "work requirements" have been a relatively uncontroversial policy on both sides of the aisle. A recent Axios-Ipsos poll found that almost two-thirds of people surveyed (including 49% of Democrats) do support work requirements for accessing public assistance. "The logic here seems neat and clean," writes James Surowiecki for The Atlantic, "And work requirements also seem morally just to numerous voters."

Work requirements are a good talking point.

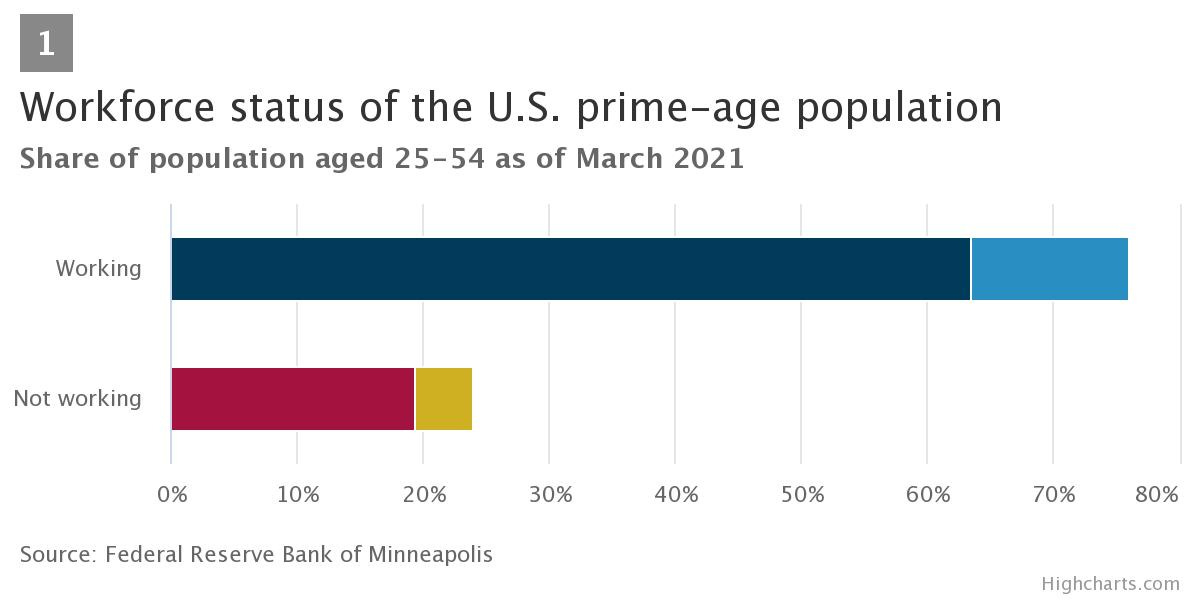

Most American adults work. Many work in jobs they dislike or even hate. Many are underpaid, underutilized, or subject to absurd scheduling policies. It's easy to imagine "not working" as unequivocally better than working. Add in cash assistance from the government? And you have fertile ground for sowing frustration and resentment.

Politicians can court votes by stoking the flames.

By painting TANF and SNAP as handouts to people too lazy to work, they curry favor with voters. Steve Scalise, House Majority Leader, recently put it this way on the floor of the House:

Should a single mom – who's working two jobs – have to pay for somebody who's sitting at home who just chooses not to work? Look, this is America. If you want to sit at home and not work, that’s your prerogative, but should you be asking a hardworking taxpayer to pay for you – 35,000 or more a year – to sit at home when everybody's looking for workers?3

They can appeal to common sense.

Comments from politicians with more practical personal brands, like Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, tend to point to helping people find jobs to escape poverty. He told reporters:

What happens when someone gets a job? They get better pay. They're able to buy their houses. But it also helps our supply chain going forward.4

Other supporters of work requirements take an altruistic angle.

They talk about the dignity of work and supporting oneself and one's family. Merrill Matthews, who works for the free-market think tank Institute for Policy Innovation, wrote in an opinion column for The Hill that work requirements help:

...those who have been on welfare regain the sense of dignity that comes with work and being able to provide for themselves and their families.

So people who support stringent work requirements have three core talking points:

Resentment: You're working, and they're not

Common Sense: People who work can cover the cost of living on their own and save taxpayers' money

Altruism: Working is good for people

Already, you might see the foundation of entrenched beliefs about work. It’s our moral duty to work hard. Working hard is how we make our way in the world. Work gives us purpose and offers self-expression.

Are these talking points—and the entrenched beliefs related to them—true?

Let’s take a closer look.

Coded within these talking points is, of course, a fundamental misunderstanding of the state of work, especially for those with lower incomes.

People receiving TANF are often shuttled into minimum wage jobs (as low as $7.25 per hour)—which isn't enough for one person to live on, let alone a family. They may work multiple jobs or quickly turnover from one job to another in search of a better situation. They're definitely not "buying their houses." Nor are they boosting their self-confidence or realizing the dignity of work since low-wage jobs are often plagued by undignified policies and conditions.

But work requirements aren't all bad—at least for one group.

Work requirements are a serious boon to companies.

By requiring poor people to work to qualify for assistance, the welfare policy creates a desperate underclass of workers who lack bargaining power, time to search for better work, or the means to gain the skills they need to escape the cycle of low-wage employment. Work requirements shift market forces in favor of employers.

Some members of the business community claim the opposite. Public assistance raises the amount someone needs to get paid to overcome the benefits of staying home, they say. However, work requirements negate that—people subject to work requirements don't have the choice to stay home, so their economic calculations are moot. Work requirements ensure that there is a surplus population to keep wages artificially low.

What's more, supporters of work requirements don't tell us that there is a mirror system of government contracts and tax credits that incentivize the creation of very low-wage jobs. The Work Opportunity Tax Credit (again, who could argue with a name like that?) provides employers with a max credit of between $2400 and $9600 (the average credit appears to be $1200) to employ people from designated groups "who have faced significant barriers to employment," including those receiving public assistance, according to the IRS website.

Workers in low-wage jobs are likely to turnover faster, allowing the WOTC to be claimed multiple times for the same worker by different employers (to qualify, a job only needs to last 3-6 weeks). A job that qualifies for the WOTC doesn't have to be a job that alleviates the need for welfare or food stamps. It doesn't have to lift someone out of poverty. It doesn't have to provide health insurance, time off, or a schedule that meets a worker's needs.

In this way, employers can create inadequate garbage jobs with confidence that there will be people to fill those jobs.

Work requirements are also great for for-profit welfare administrators.

The Uncertain Hour and American Public Media did extensive reporting on the welfare-to-work system and published that reporting in a series earlier this year. They spoke with Pat Delessio, a legal aid attorney who often works with low-income families, who characterized the system this way:

Poverty is big business. We have privatized so many of these programs. There's money to be made regulating poor people.

Those "privatized" programs are another leg of the work requirements scheme. For-profit companies manage welfare benefits in many areas. Those companies provide counseling and training for recipients. They also help with job placement.

Written into their contracts with the government, these companies receive "performance outcome payments." That means they get bonuses for how many people they get into jobs in addition to the funds they receive to administer the programs. But again, there is no baseline of quality for these jobs. In fact, these bonuses can also be claimed over and over again for the same workers since jobs only have to last 30 days to qualify. The result is tens of millions of dollars paid to for-profit companies in the state of Wisconsin alone (where The Uncertain Hour did the bulk of their reporting).

All work is not created equal.

In the most disingenuous part of his extremely disingenuous column for The Hill, Merritt Matthews invokes the spirit of Karl Marx to claim that Marx would approve of work requirements since work is part of our self-expression as humans. I only mention this because of its sheer absurdity. I had to tell someone and that someone is you! Matthews, of course, completely botches Marx's philosophy of work. Labor under capitalism is not the kind of work Marx has in mind when he talks about the benefits of work. In fact, he says as much as he defines alienated labor and how it denies workers their "species-essence" (i.e., homo faber, "man the maker"):

Similarly, in degrading spontaneous, free activity to a means, estranged labor makes man’s species-life a means to his physical existence.

The consciousness which man has of his species is thus transformed by estrangement in such a way that species[-life] becomes for him a means.

Work requirements take alienated labor to its extremes. Not only do these policies allow employers to offer inadequate and alienating work, but they also incentivize the creation of inadequate and alienating work. Workers lose all negotiating power because they compete with others subject to work requirements for low-wage jobs. People are forced to fill roles that don't improve their lives or provide for their families so that employers can enjoy tax incentives and higher profit margins.

We all play a part.

Those same employers claim they can't meet consumer needs without low-wage jobs—that is, they can't be open as many hours, they can't ship as fast, can't provide cheap food. We've come to expect the conveniences that low-wage labor facilitates. So just because we're not low-wage employers (I hope), we're still implicated in this devastating problem.

Our own jobs, many of them "bullshit jobs," give us our own sense of entitlement. "Jobs have reversed from the means to the ends, the ground to the figure," writes Douglas Rushkoff in his book, Team Human. "They are not a way to guarantee that needed work gets done, but a way of justifying one’s share in the abundance."

We've come to expect that there will be people who fit their lives around ours. We've come to believe that we're entitled to 24/7 grocery shopping, cheap burgers, and waitstaff that smile on command. We expect our coffee with extra chocolate sauce ("More!") and our t-shirts to cost about the same as a bottle of water. "Thanks" to the pandemic, we know we can treat retail and service workers as disposable—not unlike the masks so many shoppers didn't wear over their noses.

The workers who serve us, offer app-based conveniences, and do the work we’d rather not know existed, fill the bottom rungs of a socio-political ladder. Our participation reinscribes this hierarchy. But not to our benefit (even if overnight shipping is nice). The working underclass serves us at the same time that they remind us to follow the rules, put in the extra hours, go above and beyond. Don’t complain, don’t negotiate, don’t try anything fancy.

We could always end up like them.

“Us” and “them,” of course, is a false dichotomy.

The consumer market and the labor market are inextricably entwined. We work to shop, and we shop to work.

As I said at the top, we all work in the labor market where these expectations have become institutionalized. We all work in a culture where the "dignity of work" goes unquestioned despite the systems that ensure so much of the work on offer is undignified.

These policies, this culture, these institutions—they shape our perceptions of work, too. The specter of laziness, the threat of being called a moocher, the indignity of being labeled a leach—they hang over our heads. The attitude about work that we hear from employers deemed "pillars of the community" and politicians with "pro-work" agendas shapes how we think about work.

It shapes what we ask for in a negotiation. It influences the bullshit we put up with from clients or bosses. It colors the self-talk we engage in when things feel like they're just too much.

This is not to say, of course, that workers who don't struggle with poverty or lack of access to adequate pay and benefits have it as bad as those who do.

My point is that we must not take the bait.

The system is designed to separate us—to make us feel like we're better than those who receive public assistance. The rhetoric is designed to dismantle our potential solidarity.

Our job is to never relent. Our project is solidarity. Our work is realizing the ties that bind our fates.

I’m writing this as a white, woman middle-class knowledge worker from a working-class background. And I am assuming that the bulk of readers are coming from a similar class and work experience—even if we don’t share race, gender, disability or other identities. So that’s the perspective I’ve deliberately taken throughout the piece. This perspective is inherently limited—but my hope is that I’ve done some justice to thinking and writing about the issue.

There is so much that I could cover around work requirements (racism, xenophobia, ableism, sexism, etc.) that I can’t fit into today’s piece. I highly recommend checking out The Uncertain Hour’s sixth season which does some extraordinary reporting on the explicitly racist origins of work requirements, the “perverse incentives” of for-profit welfare administration, and the fact that a huge percentage of welfare recipients end up bouncing from temp job to temp job.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has a good explainer of how work requirements don’t cut poverty. And sociologist Matthew Desmond has done extensive research on the causes of poverty in the United States.

It’s much easier to explain the so-called “labor shortage” as a shortage of adequate jobs than it is a shortage of people working.

McCarthy out there saying the quiet part out loud: supply chain!

Subscribe to What Works

What Works is a newsletter and podcast about work, the many ways it shapes us, and how we can better shape it.