How to Rethink Work Stress

The stress of work can be especially tricky to describe for creative and knowledge workers who love what they do. That doesn't make it less real.

Work in a way that builds you up instead of breaking you down.

If you’re trying to work in a more sustainable way but find yourself backsliding into old habits, it’s time to Rethink Work. Join me for this new cohort-based course!

Where does a politician go when they want to talk about creating more jobs?

They don't go to a high-rise office building. They don't visit the insurance agency storefront in an office park. They don't go to the local restaurant with a "Now Hiring" sign emblazoned across its front door for the last three years.

They go to a factory.

When a politician wants us to think of them as a job creator, they use The Factory as a metaphor. Like jobs get produced on an assembly line of public policy.

The Factory is an outdated metaphor for work today—less than 10% of US workers are employed in manufacturing. But that metaphor still informs how we think about work and what we expect from ourselves as workers. Productivity, efficiency, standardization, automation, output—we often rely on concepts that govern industrial and manufacturing process management to describe work that defies the very definition of those terms.

When we try to squeeze creative, knowledge-based, service, or care work into the mental model of The Factory, we create confounding and stressful working conditions for ourselves (and often for others). And because our work is often framed as a privilege, we have a hard time recognizing and describing the stress we feel so that we can address it.

So why does The Factory, as a metaphor, still permeate our disposition toward work?

I've never worked on an assembly line, but I can picture one. I'm sure you can, too. I can easily imagine what that kind of job would entail (which is not to say that kind of job is easy or desirable—just imaginable). However, I have no idea what the average architect or home health aide's job is like. I've eaten in plenty of restaurants, but I don't really know how the job of a server or line cook works. I ostensibly work full-time as a writer, but the daily work of other writers is basically a black box to me.

In other words, The Factory lacks the inherent ambiguity and uncertainty of more 21st-century modes of work. We want metaphors that translate easily across different groups of people. I can have the perfect metaphor for some complex topic, but if my metaphor isn't recognizable to you, it doesn't work.

But The Factory is an abstraction.

What I think of when I think of an assembly line or manufacturing workshop is different from what factories are really like. The metaphor itself becomes a blueprint for reality. The goals I set for my work are built according to this blueprint. My expectations for how I perform are directed by this blueprint. The challenges I face and the solutions I seek to create are based on the logic of this blueprint.

As time goes on, I get frustrated because the blueprint I'm working with doesn't actually match what I'm trying to make. It's like trying to build a BILLY bookshelf with the instructions for a MALM bed frame. The parts don't match, the steps make no sense, and I just can't figure out how this bed frame is supposed to organize all of my books. Alright, I'm mixing metaphors now...

That frustration—that confusion—is at the heart of so many of the problems we face with work today. Setting aside the economic, political, and cultural issues that vex our working lives (a big ask), the mental model we have for work is just wrong.

Let's make this frustration and confusion more concrete by looking at three specific types of work.

Management researcher and theorist Armand Hatchuel labels our frustration and confusion "work intensity." He argues that work intensity functions differently for different types of work—that means that different types of work need different strategies for mitigating or combatting work intensity.

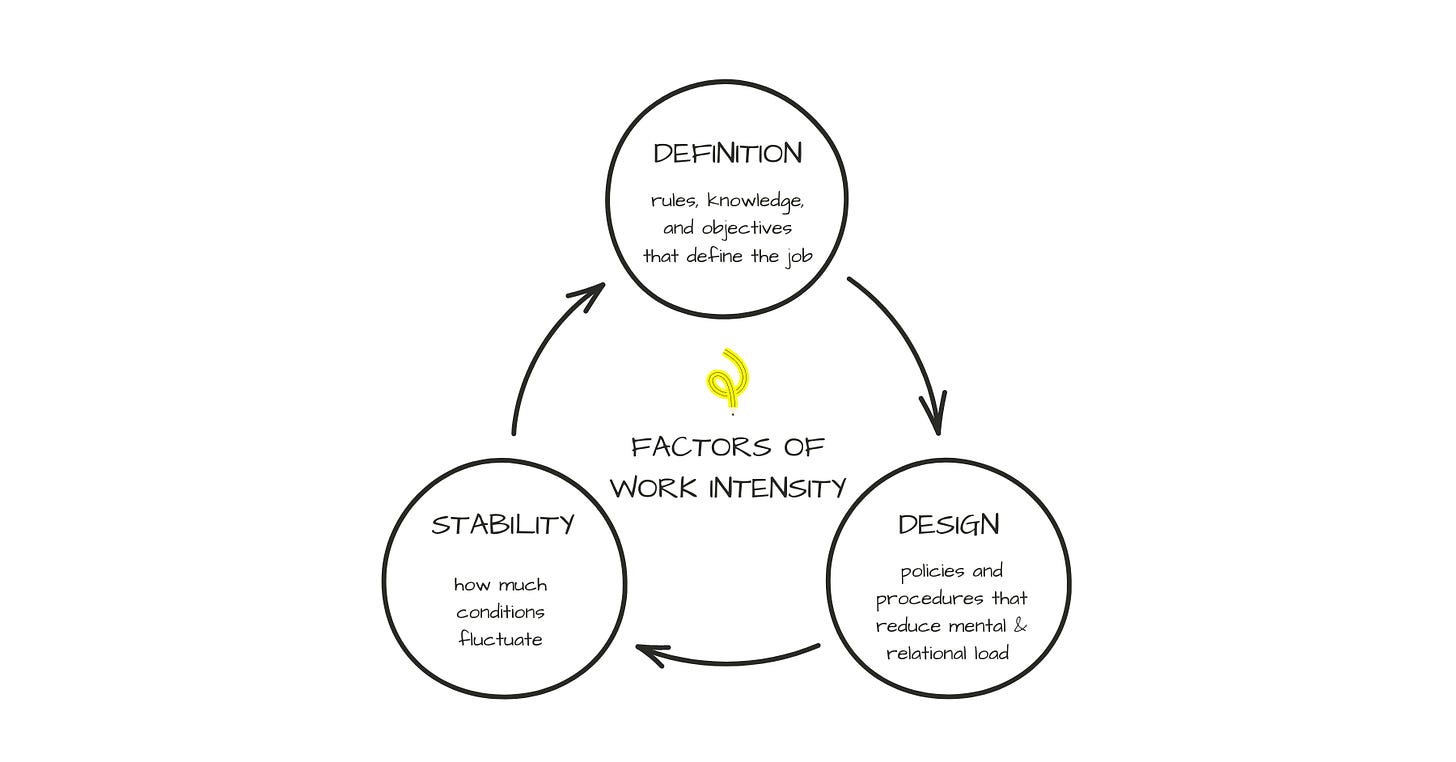

To figure that out, Hatchuel offers three factors of work intensity: definition, design, and stability.1 The definition of a job is the set of rules, requirements, knowledge, and objectives that give it shape. The design of a job is the policies and procedures put in place to limit the bounds of the job and reduce the mental load it requires. The stability of a job is the amount of fluctuation the worker can expect in the job's tasks and responsibilities from day to day.

Another way to think of it is that definition is a function of the job itself and its associated tasks. Design is imposed by management to make the job as stable as possible. And stability (or lack thereof) is understood over time.

Hatchuel illustrates these aspects through 3 types of work: factory work, bus driving, and creative or knowledge-based work.2

A factory worker's job is highly defined, designed, and stable.

The archetypical factory worker shows up to a day at work knowing exactly what their job is, how to complete that job, and what the rules around that job are. Management creates training, policies, and procedures to limit the job and reduce its mental load. Management further controls all work conditions—equipment, raw materials, schedule, location, etc.

A bus driver's job is pretty different.

It is still highly defined, but the design and stability of the job are lower than in the case of a factory worker.

While a bus driver still follows a strict schedule, expectations, and rules, the driver has a great deal of autonomy on the road. They can't change the route, but they are responsible for dealing with how passengers and traffic can create unexpected (and unwanted) changes in their working conditions. Aside from a radio connection to dispatch, they're on their own. Further, sometimes a bus driver's job isn't driving the bus at all—sometimes it's counselor, moderator, knowledgeable citizen, or overdose interrupter—the boundaries of what is and what isn't the job of the bus driver are constantly changing.

The example of the bus driver makes me think of my time in retail management, too. The people I managed had relatively defined jobs, especially at a task level: cashier, barista, bookseller, etc. They received training in how to use all of the tools of the trade: cash register, inventory system, espresso machine, etc. We even did our best to train them on how to recommend books, respond to customer questions, and keep an eye out for theft.

But workers still had plenty of autonomy when they were on the floor. I couldn't observe the thought process that went into a customer interaction. I wasn't actively controlling the flow of work in the café. As a manager, of course, I had even more autonomy and self-management responsibility. That meant that I had to step in when work design systems failed, and the situation got too unstable. I could see the consequences of work intensity on the people I managed and on myself.

Finally, we arrive at the creative or knowledge worker.

This job is moderately defined, with low design and stability. Creative and knowledge-based work (and also most service and care work) is fluid, amorphous, and often ambiguous. Each worker is a sort of node in a system—the connections between nodes are critical but also subject to change at any time.

Like the factory worker, the creative or knowledge worker can only do their job if someone else in the chain does theirs. But unlike the factory worker, what each person in the chain does isn't well defined. Each consecutive person who picks up that widget from the assembly line sort of makes it up as they go. One worker builds on or adjusts the widget based on what they know about widgets and how they interpret their role; the next worker takes what that worker has done and builds on or adjusts the widget based on what they know and how they interpret their role.

Hatchuel argues that this high reliance on others combined with the ambiguity around one's job increases work intensity. Further, adjusting that intensity is more complicated because the work processes involved are often personal and unarticulated rather than physically observable. In other words, we get the familiar anxiety of “I feel like something could go wrong at any time… but I don’t know why or how to fix it.”

“I feel like something could go wrong at any time… but I don’t know why or how to fix it.”

The creative or knowledge worker also has plenty in common with the bus driver. They both have considerable autonomy (read: responsibility) over their self-management and responses to changes in conditions. However, the bus company can mitigate work intensity for drivers by observing patterns, designing new training, and equipping drivers with new strategies. Since drivers' difficulties on the road are easily observed and defined, the company can create solutions or policies to offer drivers more support (and stability).

But the creative or knowledge worker is in a pickle. Workers face novel challenges every day. In fact, they're often tasked with inventing novel challenges since their jobs revolve around working with new ideas, designs, and solutions.

When I send out a newsletter, I risk getting something wrong and inspiring an inbox full of unexpected emails—which then changes how I spend my day. When I post something on social media, I am creating the potential for a post to go viral—which is destabilizing even if it's positive! When one of our podcasting clients logs into a Zoom session with Sean and me, they're often creating unexpected work for themselves by asking for our opinion on their content.

Doing just about anything at all in the realm of creative, knowledge, or service work can open a can of worms.

Creating training or policies to address this barrage of novelty is nearly impossible. So, no matter the intentions and resources of the employer (or self-employed person), the work can be deceptively intense.

That deceptively high intensity is a narrative problem, which is to say that it's a problem with the stories we tell ourselves, which is to say that it's a metaphor problem. Our mental model of The Factory obfuscates why we experience stress or confusion—and offers remedies that can’t actually fix our distress.

We can easily understand why a factory job would be stressful (e.g., dangerous machinery, unreasonable quotas, etc.) or how a bus driver might be regularly frustrated (e.g., acting to diffuse threatening situations). But the creative or knowledge worker has it easy, right?

We often downplay our stress or strain because we don't have a way to articulate exactly what is so intense about what we do.

To be clear, I'm not saying that factory workers or bus drivers have it easy. I'm not even saying that creative or knowledge workers are in a worse spot. My point is that most of us don't know how to recognize or describe the source of stress and intensity of a job that we might well perceive as fun in the right circumstances.

The lack of recognition or description doesn't change reality, though. It just makes it harder to deal with.

To cope, we often try to turn creative, knowledge, and service work into something that resembles factory work. That's the power of a foundational metaphor like The Factory. You can see the influence of The Factory on the landing pages for top productivity apps, on book covers, and across YouTube channels.

How to do more in less time. How to optimize everything. How to automate your life.

As a result, we talk about automation, productivity, and efficiency. We wring our hands over the details of a process or rule. We decide to have stronger boundaries. Set a reasonable schedule. Take less shit. Unplug.

These objectives can have merit—well, not the hand-wringing. But I see many people get down on themselves when they don't follow through on their commitment to a saner working life. The truth is that stabilizing inherently unstable work is a Sisyphean task. Making one aspect of the creative process more efficient will destabilize a different part of the process. Standardizing an element of your job might make you more productive in one area but destabilize another element of your job.

The truth is that stabilizing inherently unstable work is a Sisyphean task.

What's more, who honestly believes that optimizing creative, knowledge, or service work leads to better outcomes? Who believes that innovation happens in assembly line conditions? Who believes that care and service work is best done by adhering to a strict schedule and set of rules?

The more we attempt to squeeze creative, knowledge, and service work into the metaphor of The Factory, the more likely we are to burn out. Not so much because we're working hard but because how we're trying to work isn't aligned with what we're trying to make.

I’m updating the labels that Hatchuel uses for these aspects of work. My labels correspond to his labels: prescriptions, design, and confinement, respectively.

Again, I’m updating a term. Hatchuel's third worker is described as a "white collar" worker.