How the Game We Play Changes the Way We Work

Etsy, Game Theory, the NFL, Layoffs, and Absentee Capitalism: You have to know what game you’re playing to know how to win—and you also need to decide whether that’s the game you want to play.

I started to pay attention to micro businesses and “new” ways of working by studying Etsy sellers.

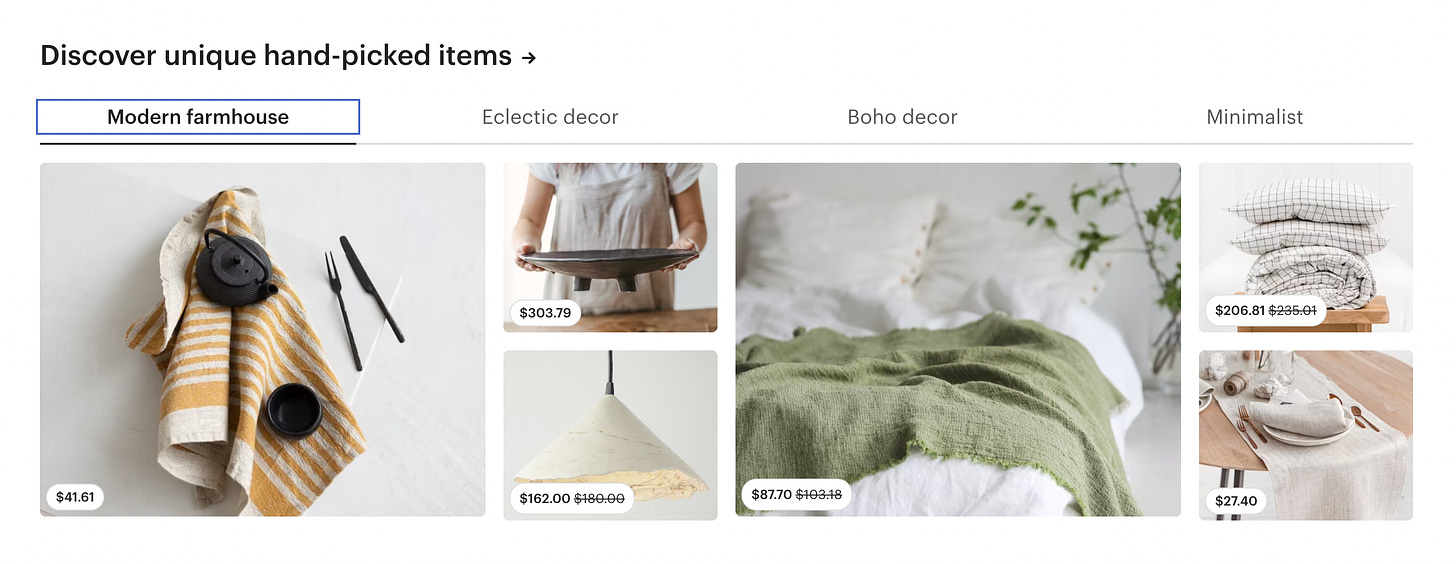

This was 2008-9 before the platformization of the site had wreaked havoc on its aesthetic and public perception. At that time, the chief way an Etsy seller could get noticed was through their photography. So-so photography might get you a few sales, but beautifully lit, softly focused editorial-style photos could get your shop on Etsy’s homepage and featured by major maker blogs (I ran a smaller but well-recognized maker blog at the time). Those features could bring in hundreds of sales overnight—and catapult the Etsy shop into the market consciousness in a wholly different way.

By 2010, great photography wasn’t a nice-to-have, it was a necessity. Sellers scrambled to learn photography skills, construct homemade light boxes, and develop an eye for composition. Imperceptibly at first, but with growing clarity, makers realized they were no longer makers. They were photographers who made things.

What was made became secondary to how that thing was photographed.

The business of selling on Etsy went from a business of producing handmade products to a business of merchandising aesthetics.

This was, quite literally, game-changing. To win, sellers had to stop playing the old game and start playing the new game. Early on, products gained traction based on the product's qualities—craftsmanship, design, novelty, etc. But the new game of attention—and, therefore, sales—involved the qualities of photos in the product listing. The product was merely a prop, an artifact of the platform’s prevailing aesthetic.

In effect, you could game the Etsy market by focusing almost exclusively on gorgeous photographs.

What does it mean to “game a system?”

Depending on who you are and the groups you’re a part of, “gaming the system” can be considered heroic or villainous, virtuous or exploitative, creative or extractive, above board or (vaguely) criminal. Gaming the system means learning a system well enough to leverage its constraints and capabilities to your advantage.

Philosopher C. Thi Nguyen describes games as often possessing a “motivational inversion.” In a game, we might be motivated to do things that we wouldn’t do outside the game (e.g. throw a ball through a hoop or pretend to have magical powers). Further, he describes the invention of a game as the “art of agency.”

Games provide us with a goal, a method, obstacles, and a set of rules that encourage us to utilize our agency toward the ends of the game.

“A game uses all these elements,” he writes, “to sculpt a form of activity. And when we play games, we take on an alternate form of agency.”

Many Etsy sellers experienced a motivational inversion back in 2009. Even if they didn’t have an interest in learning photography or product merchandising before they started to sell on Etsy, the rules of the game motivated them to take up that goal. Their agency became directed to putting together a shop that matched Etsy’s preferred aesthetic, rather than crafting high-quality products.

Platforms like Etsy—or Facebook, TikTok, Twitter, Uber, DoorDash, and, yes, Substack—instantiate a sort of game architecture. They provide users with a goal, a method, obstacles, and a set of rules. They tend to do this implicitly rather than how a true game does it explicitly. People who “game the system” work within the implied-but-real conditions of the game to devise a strategy that the game designers didn’t anticipate. This has the effect of granting outsized power in the system to those who use the strategy.

If the strategy seems to ultimately benefit the game designers, they may recognize and reward the power of those who use it. This is what Etsy did with the shift to a focus on photography. A shop simply couldn’t gain a prominent spot on the Etsy blog or homepage without impeccable photos. This further entrenched the power of the new strategy. But if the strategy seems to disadvantage the game designers (or, they simply don’t like it on moral or aesthetic terms), then they’ll counter users’ power by changing the rules or closing the loophole.

The Business of Rule Changes

The NFL has enacted many prominent rules changes over the years. It seems they do this for two reasons: one, for safety (e.g., the 2013 rule change limiting contact with another player’s helmet), or two, for entertainment (e.g., the 1974 rule change limiting defenders’ ability to interfere with kick receivers). Even very early in the history of football, rule changes were made in the name of more exciting games:

“In a 1940 report, the Rules Committee stated bluntly: ‘Each game should provide a maximum of entertainment insofar as it can be controlled by the rules and officials.’ The entertainment value of the game, it added, could be measured by ‘the number of plays per game of a type that will be pleasing to the audience.’”

Even before Monday Night Football or broadcast television, the NFL understood the real game it was playing was entertainment.

The game of football was (and is) contained within a meta-game, that of appealing to fans (and, therefore, advertisers).

We can understand the Etsy example in a similar way. Sellers were engaged in a photography game. The goal was sales through publicity and features. The method was a particular type of photographic style. The obstacles included equipment, skill, and design aesthetic. But this game was contained within the meta-game the platform itself was playing. Etsy’s business model is largely based on a variety of seller fees. But it’s not enough to say that Etsy plays a “seller fees” game.

Etsy plays the capital game.

Sure, its leading goal is maximizing fees to drive profit. But ultimately, its objective is to generate capital for its shareholders. And while these goals are related, they’re not the same thing. They’re related—but they’re not attached to each other in any causal way.

The Profit-Growth Game

Ed Zitron recently wrote of “absentee capitalism,” arguing that:

“…production has become almost entirely separated from capital, meaning that executives (and higher-ups) are no longer able to understand the nature of the businesses they are growing.”

Executives, like those at Etsy, are tasked not with producing a better product to drive sales via seller fees. Instead, they are tasked with driving the growth of profit. They are in the profit-growth business, not the business of marketplaces, consumer goods, communities, etc.

When the development of a better product and the growth of profit are moving in the same direction, we don’t notice the way executives base decisions on the rate of growth. But when building a better product and growing profit are in any way at odds, it will always be the product (and therefore, the customers) that suffer. That’s just the game they’re playing. The ‘agency’ of the business is directed toward profit—and not just profit but, as Zitron writes, “more profit than they previously had.”

Take the recent shuttering of BuzzFeed News.

BuzzFeed News was a Pultizer Prize-winning newsroom that did serious investigative work. Sure, its namesake is known for silly listicles and quizzes—but BuzzFeed News was the real deal.

“Despite what may have been Ben’s dream, we never competed with the New York Times or legacy outlets; we were always playing an entirely different game. Not better or worse, just different. We succeeded when we looked for stories in places no one else was looking precisely because we couldn’t compete with legacy outlets on the main story of the day.”

— Katie Notopoulos in “The Ultimate Oral History of BuzzFeed News”

(Emphasis added.)

The news division was expensive, especially compared to the “cheap” media that drove traffic on the clickbait side of the company. But nurturing the upstart newsroom was an acceptable bet while the company was still growing.

As the media environment and economic conditions started to change, the product started to move in a different direction from the growth of profit. After BuzzFeed went public in 2021, the newsroom was out of time. The operations of the company depended on whether shareholders were happy—and they wouldn’t be happy unless the company was creating more capital for them. The game had changed, and BuzzFeed News didn’t fit into the rules anymore. And now, up to 180 people are out of a job.

If you’re traditionally employed in a company where growth is paramount, your role is contingent on how well the company games the capital system.

As long as new capital is being generated at an increasing rate or new investment is flowing into the business and creating more theoretical capital for investors, your job is relatively secure. But as soon as the rate of profit growth slows or new investment gets harder to come by, your job could be on the chopping block.

Neither the indirect value you produce for your employer nor your direct involvement in the production process is enough to secure your job because the company you work for isn’t in the [insert product or service here] business, it’s in the profit-growth business. Making a solid profit margin on a good product just isn’t enough to satisfy investors.

But this doesn’t just impact publicly-traded firms, or even companies with private outside investors. Because so much exchange is mediated by platforms, even very small businesses tend to adopt this mindset. Writer and communications scholar Moira Weigel studied the small businesses that account for a large segment of Amazon’s business, the Amazon 3rd Party Sellers. “Time and again,” she writes, “interviewees described how succeeding on Amazon required them to behave like miniature Amazons.” She argues that platform capitalism is “remaking the opposition” between big companies and small businesses.

Before 2010 or so, we would have put giant multinational companies into the “greedy capitalist” category and bemoaned the way they make decisions based solely on making shareholders happy. And we’d put small businesses in the “mom and pop” category, celebrating their holistic and human-scale approach to business.

Both categories are reductive—but those are the narratives, right?

But today, the motivational distinction between these categories is fading. Consider the influencer who is “only doing it for the likes” or, yep, the Etsy seller focusing more on photography than craftsmanship. I am not blaming or shaming anyone who has learned to play the game—only observing that the games that large and small businesses play are starting to become the same game.

Creating Loopholes

To return again to “gaming the system,” one thing a company can do when growth slows is to use technology or market innovation to change the rules. New technology and market innovations create loopholes in the existing rules—and savvy executives take advantage of those loopholes.

When Zuckerberg decided to go all-in on the metaverse, he thought he was leveraging an emergent loophole. Facebook, still wildly profitable, just not seeing profit grow at the same rate as it once did, would become Meta and mine profit from a new market. When Netflix started to produce its own content, it created a new channel for profit growth. When Apple started to produce iPods, then iPhones, then Watches, it used product development itself to change the rules.

Just as the NFL uses a rule change to make the game more entertaining, a company uses a change in the market to make the game more profitable. And just as NFL players have to readjust their gameplay based on that rule change, workers have to adjust when a company makes a change. Because NFL rule changes are typically pretty minor, it’s really not a big deal for players—or so I imagine. But for workers, a shift to a new market or profit strategy exacerbates their instability and uncertainty. It often means layoffs, restructured contracts, or more intense workloads.

Those of us working outside of traditional employment have our own rule changes to consider.

Etsy sellers learned to become as much photographers as they were artists or craftspeople. On Instagram, influencers who once saw growth because of the pictures they posted learned to share videos instead. When it seemed that online courses weren’t as profitable as they once were, creators learned to become community builders.

What’s more, I don’t think a lot of independent workers and small business owners actually know what game they’re playing. The one that seems obvious is merely a secondary consideration. Just as a CEO needs to know more about playing the capital-growth game than the product their company makes, many small business owners have found themselves playing a social media growth game or an email marketing game rather than a game based on the offers they sell.

While individual creators or small business owners aren’t beholden to the interests of shareholders per se, they often experience trickle-down effects from companies that are. And again, that exacerbates already existing uncertainty and instability.

The WGA strike is emblematic of this.

Two of the WGA’s chief demands are restructuring pay so that writers can recoup real losses they’ve suffered because of the move to streaming and gaining assurances that AI will not be used to replace them. The move to streaming was a loophole that studios used to change the game. And the potential leverage of AI is a loophole-in-waiting. The studios gamed the system in service of capital growth without regard for the impact on writers—who play a huge role in whether what the studios produce is any good.

The studios aren’t in the content or entertainment game at all. They’re playing the profit-growth game.

The internet seems to be in a rebuilding year.

The tools and media we use to make a living here are in flux. Executives are tightening their belts and biding their time before the new rule changes can take effect. Independent workers and small business owners have their eyes out for the next loophole. We don’t know if we’ll need to become photographers, or dancers, or magicians, or orcs to score points in the new growth game.

Many business ‘gurus’ will tell you that, “if you’re not growing, you’re dying.”

I used to believe it, too. My experience was that, if I wasn’t doing what it took to grow, then churn would inevitably cause my business or influence to shrink. As a result, I played the growth game more than the game I actually wanted to be playing. And because I focused on growth, I couldn’t focus on improving my product or producing remarkable content.

The opposite of growth, in this case, wasn’t churn—it was maintenance.

So I might rephrase that adage: “If you’re focused on growing, you’re not focused on maintaining.”

Okay, not as catchy. But again, growth is not the only goal. What could an impeccably maintained work-life look like? What could an impeccably maintained company look like?

It’s not necessarily smaller or slower (although, it might be). But it would be free “from constant churn of recomposition and reorganization,” as Gavin Mueller put it. It would shed the anxiety that comes along with looking for the next loophole to exploit or strategy to employ. To use Zitron’s “absentee capitalism” framing, quitting the growth game might mean stepping into a sort of presenteeism with one’s work that we’re rarely afforded today.

To be present with satisfying and meaningful work sounds like a valuable game to play.