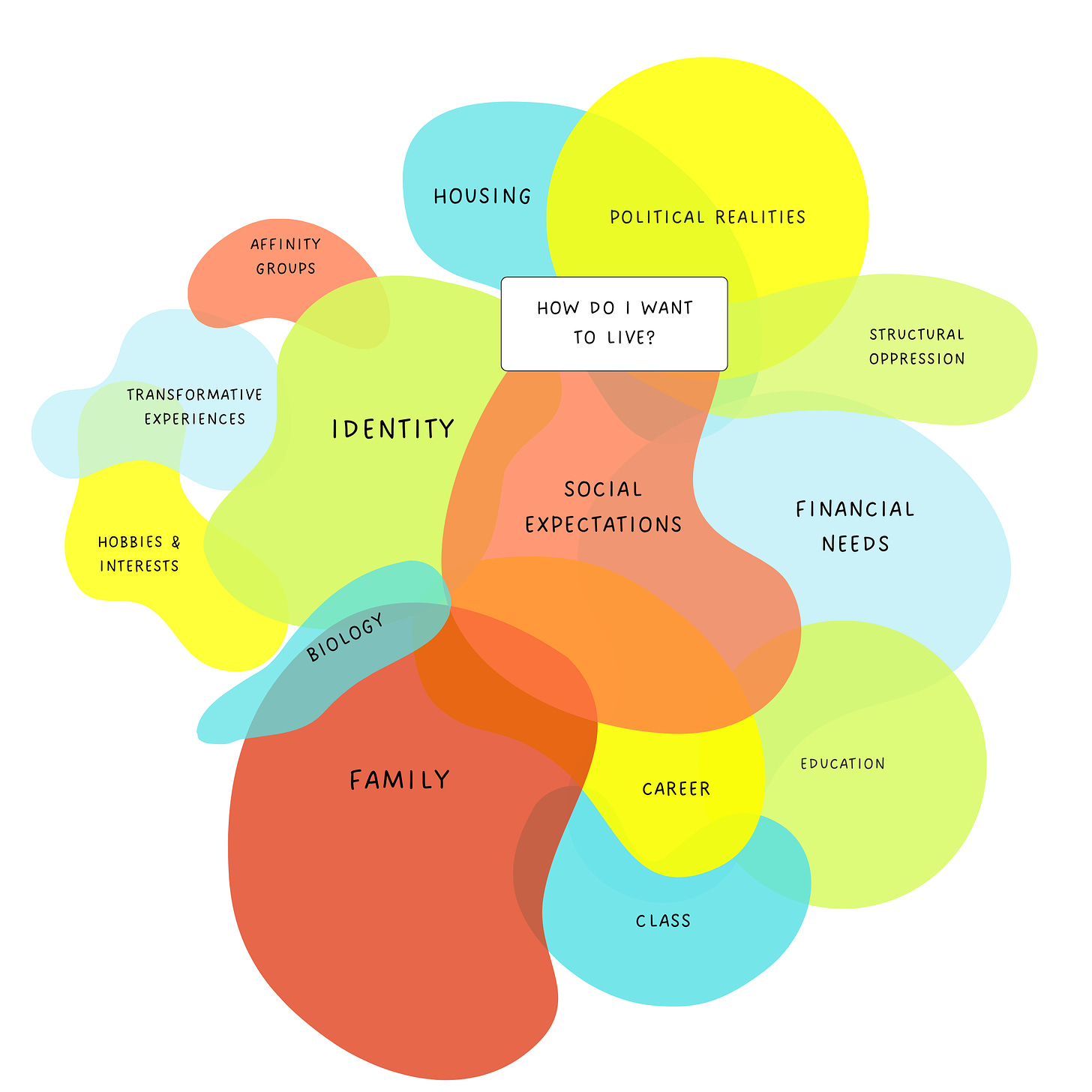

How Do I Want To Live?

We can't decide how we want to work until we decide how we want to live.

At a conference last month, I facilitated a wide-ranging conversation loosely about entrepreneurship and identity. Eventually, the conversation landed on education and the careers we thought we had prepared for. One woman shared that she'd recently talked with a college-bound person who was somewhat undecided about what they wanted to do for a living.

Her advice? First consider how you want to live before considering what you want to do for work.

I could hear sharp breaths around the conference table as participants retroactively received this advice. One woman said she wished she'd been asked how she wanted to live when she was that age. Others echoed this regret.

It's never too late, of course, to ask the question: How do I want to live? It's a question that often arises post-burnout. Many people ask it when they recognize they've become victims of their own success. So many small business owners I've talked with over the last 15 years have asked a version of that question once they realize that the business they've built is not the business they actually want to run.

Just a few days after this conversation, I was due to teach on the concept of alienation. As I reviewed my notes, I was reminded of this dense passage in Rahel Jaeggi's book, Alienation.

Thus the theory of alienation entails the idea of a qualitatively different society (Herbert Marcuse); alienation critique is always already bound up with the question of how we want to live. In its negativistic approach, the concept of alienation investigates not only what prevents us from living well but also, and more important, what prevents us from posing the question of how we want to live in an appropriate way. (emphasis added)

Here, Jaeggi says that we can't consider the concept of alienation without also considering the question of how we want to live. Of course, the reverse is true, too; we can't consider the question of how we want to live without also considering the condition of alienation. Further, we can't ignore the ways that our alienated condition obstructs our vision. Without a serious critique of the forces that lead to a state of alienation, we can't meaningfully contemplate how we want to live.

I spent the weekend thinking about forces. What are the many pressures that exert themselves on the things we're trying to understand? How do we understand the countervailing vectors at play in every choice we make?

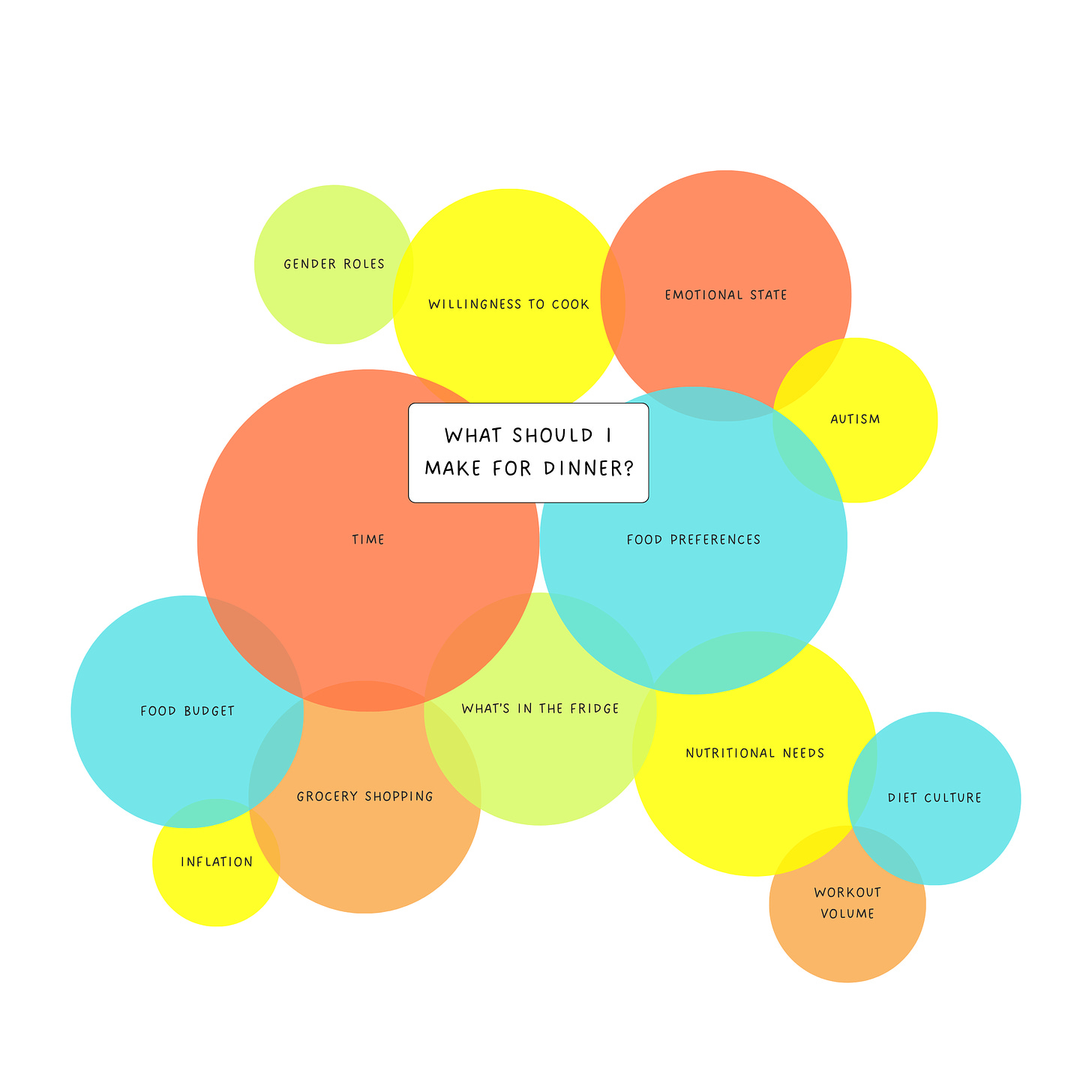

If I'm trying to figure out what I want to make for dinner, there are the forces of time, food preference, nutritional need, and willingness to cook. Beyond those forces, there are additional layers. For example, the force of time is further impacted by the supply of food in my kitchen. That is, do I need to go to the grocery store to make what I want to make? And do I have time for that trip?

The question, "What should I make for dinner?" looks something like this in my head:

There is no tidy flow chart or decision tree that I could make to determine what to make for dinner. The choice I make is the product of forces with varying strengths. Some days, "time" is the major factor. On other days, "diet culture" will win out, even though I intellectually know that cultural pressure shouldn't ever sway my decision. And on other days, I might be glad just to find a happy medium between "what's in the fridge" and my peculiar "food preferences."

Jaeggi analyzes the forces at play when it comes to alienation and our inability to meaningfully ask how we want to live. She identifies "conformism" and "instrumentalization" as two fundamental forces separating us from ourselves, from others, and from the world.

Conformism is the force that translates our own desires through others' desires. We learn to play a role. We become so good at playing the role that we become 'inaccessible' to ourselves; our own desires and truth are 'impenetrable.'

What does it mean to be a parent? An entrepreneur? An early adopter of the latest technology? Our roles are bound up in social expectations, career choices, and product purchases that constrain our ability to imagine otherwise.

Instrumentalization is the force that shapes our identities into tools. We identify with what we do, how we're used, and how we're valued more. We lack a sense of agency and feel beholden to those individuals or institutions that would use us as tools.

Do we become homeowners, for instance, because we want to own a home? Or because social, political, and economic forces use our homeownership to maintain the inequitable status quo? Just yesterday, Sean and I talked about how our decision to buy or rent was so constrained by economic and political forces that buying was the only choice we could make.

Both conformism and instrumentalization create the sense of "drifting through life." We're pushed and pulled with such force that many of us don't even think to ask, "How do I want to live?" And if we did, could we trust our own answers?

Prevailing self-help advice cautions against the structural critique—lest we begin to see ourselves as "victims."1 Instead, we're encouraged to draw inward. They urge retreat from the reality of outside forces and warn us to close the city gates against invading messages. Safely inside, we climb the tallest tower and attempt to discover ourselves. We take up personal responsibility as a shield. The result is a sort of siege. We're protected for a time, cut off from the outside world.

But it's not a sustainable condition. Not everyone or everything trying to get in is an enemy. We need to open the gates and restart trade with the outside world. A sustainable answer to "How do I want to live?" must be one that is willing to wrestle with the forces we exist in relationship to.

Destructive forces exist. Alienating forces exist. But so do constructive forces. Creative forces. Connective forces.

Jaeggi argues that a self-directed, agential existence isn't a wholly individualist or self-absorbed one. Freedom requires the push and pull of social forces. Those social forces organize themselves into political and economic realities. We're tasked not with finding ourselves outside of those forces but within them. Even through them. An unalienated life, one in which we're free to ask, "How do I want to live?" is a life that negotiates and renegotiates our relation to the forces that act on us.

I did not know how I wanted to live at 18, or 25, or even 35. I couldn't have. I'm not sure I know how I want to live now. But I know I would have thought differently about my life and work had I asked the question. And I know I'm much more clear-eyed about how I approach the question given the ways I recognize the diverse forces at play in the world.

If you're gathering with family this week, ask the young people (or the old people) in your life how they want to live. You might get more blank stares than answers—but that's okay. They're thinking. Differently.

More of what works:

Join me in Atlanta, Georgia on February 28 for an evening of talks, music, and film at Plywood Presents. This is a unique event for social impact leaders—and anyone looking to deepen their thinking about community-oriented change.

I’ll be leading another session of Work In Practice in 2024! I’ll have details next week—but this session will run from February 8 - April 25, 2024. Live sessions will be Thursdays at 12:30pm ET/9:30am PT.

Looking for holiday gifts? Ready to inspire people you love (or like, or tolerate) to rethink work? You can find my book recommendations at Bookshop.org!

Today’s episode of If Books Could Kill speaks to exactly this in analyzing Mark Manson’s The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. And honestly, if you’re not already listening to this podcast, you’ve got yourself some holiday listening to catch up on!

Wonderful post, Tara. I have to admit that your diagram of "What Should I Make for Dinner," which I relate to (though I'd draw mine on a mobius strip), led me to envy my cat, whose diagram would simply have one circle... labeled "Bowl."

This led me to reflect on the poetry of Zen poet Ryokan, who influenced how *I* want to live. He wrote:

Today, while begging food, a sudden downpour.

I waited out the storm in a small shrine.

Laughing—one jug for water, one bowl for rice.

My life is like an old run-down hermitage—poor, simple,

quiet.