Buying Freedom and the Freedom to Buy

The freedom-based marketing campaign that sunk national health insurance in the 1940s in America—and how those same messages resonate in the market today.

Marie Forleo bills her signature course, B-School, as the "ultimate system to grow your business and own your freedom." It's the subhead on the sales page.

Scroll down just a bit, and you'll see how she defines freedom: "Live where you want, take on clients you want, charge what you want, go where you want." Next to that is the related value of "prosperity:" "A dream business can set you up for a life of financial freedom, in any economy."

Rachel Rodgers claims her membership is where "fun meets financial freedom." Amy Porterfield's website is emblazoned with the headline: "An online business = freedom in how you work. And how much you earn." Productivity guru Ari Meisel claims automation and outsourcing are the keys to freedom: "Your greatest success, freedom, and fulfillment depends on you taking the leap and doing LESS."

Freedom seems to be a good business to be in.

But what is it that marketers, influencers, and gurus—or rather, their copywriters—mean when they say freedom? Freedom from what? Freedom to what?

In the United States, we hear about our freedom all the time. It's a "free country." We have "freedom of speech." It's the "land of the free and the home of the brave." We love the "free market." So why do I need to buy my freedom for the low, low price of $1997?

Online marketers didn't invent the freedom grift. The business of freedom—both literal and metaphorical—is ancient. I won't try to recap that whole history and its many socioeconomic implications here. Instead, I want to focus on one freedom-oriented marketing campaign that laid the groundwork for today's headlines.

That marketing campaign? It's part of the reason that the United States doesn't have a national health insurance program like the rest of the developed world.

And it begins with two young and ambitious writers in northern California.

Keep reading or listen on the What Works podcast.

Modern Political Campaigns: An Origin Story

It's 1933, and Leone Baxter works as the manager of the Redding Chamber of Commerce in northern California. Born in 1906, Baxter is a 26-year-old widow and former writer for the Portland Oregonian. For what it's worth, she tells an interviewer in 1992 that she was a fresh-faced 18-year-old planning to work for a few years before heading off to university.

Baxter catches the eye of Sheridan Downey, a prominent Californian Democrat, who hires her to work on a public relations campaign aiming to defeat a referendum on that year's ballot. Downey also hires former journalist turned media entrepreneur turned ad man Clem Whitaker. Downey suggests that Baxter and Whitaker team up.

They do, and the campaign they engineer for Downey is a success. That same year, Whitaker and Baxter start Campaigns, Inc.—widely considered the first political consulting firm in the world. Their next big project is the 1934 California governor's race between incumbent Republican Frank Merriam and muckraking journalist and author Upton Sinclair, a Democrat. Merriam wasn't a popular governor, but Sinclair posed a threat to California's big industries on account of his prioritizing the health, safety, and wallets of workers.

Whitaker and Baxter pass on an opportunity to work for Merriam because they didn't think he was a very good governor. They pass on the chance to work for Sinclair because, although they agreed with him on some issues, "on the church, on religion, on marriage, the institution of marriage, and other things that have very great importance to most ordinary people, ... we thought he was very, very wrong." Instead of the two top-of-the-ticket candidates, Whitaker and Baxter sign on with George Hatfield, the Republican candidate for lieutenant governor, who ran opposite Sinclair's running mate Sheridan Downey—Whitaker and Baxter's matchmaker.

Whitaker and Baxter set about sinking Sinclair's campaign using his own words against him. Spotlighting quotes from Sinclair's nonfiction and fiction alike, Campaigns, Inc. paints him as out of touch with the values and traditions of the average Californian. They commission cartoons and posters to bring Sinclair's supposed views to the masses. He's smeared as a communist whose policies aimed at ending poverty would instead invite a "horde of outsiders" into the state looking for a handout.

Some things never change.

Merriam wins the governor's race in a landslide. Sinclair takes to the papers to explain why he lost. And Whitaker and Baxter are just getting started. After Whitaker leaves his first wife, the business partners marry in 1938. Between 1933 and 1948, 58 of the 63 legislative campaigns they worked on were successful.

In 1948, Campaigns, Inc. is hired by the American Medical Association to work on turning the public against President Truman's plan for a national health insurance program.

The Doctor Is In (Charge): The Professionalization of Medicine

The American Medical Association (AMA) was founded in 1847 and acts as a professional association and lobbying group for doctors. Medicine, of course, wasn't always a profession, nor was the title of doctor regulated by years of extensive training and testing. Over the course of the 19th century, medicine became professionalized.

Professionalization is a social, political, and economic process that closes off a field to people whose knowledge or experience doesn't conform to a narrow set of guidelines. On the one hand, professionalization aims to protect the public by keeping out grifters and quacks. It raises standards and ensures some consistency in an industry. But on the other hand, it's a way to discredit or even criminalize ways of knowing and practicing that don't conform to those of the people in power.

In other words, professionalization tends to remove women, indigenous people, and people from outside Western white society from the ranks of experts and practitioners. What's more, professionalization robs the public of the knowledge and experience of gendered and racialized practitioners. At the same time, professionalization raises the status and wealth of those, primarily white men, who do pass the test. It reproduces hierarchy and productizes services once integrated into community care.

The American Medical Association was integral to the professionalization of medicine in the United States and actively sought to influence lawmakers to adopt AMA-backed positions, including standards for pharmaceuticals, vaccine guidelines, and fluoridated water supplies. But they also advocated at various times for limiting the supply of doctors—including successfully pushing for a cap on Medicare reimbursement for training residents in 1997. You can draw a straight line between our current doctor shortage and AMA lobbying.

So yes, the AMA has benefitted public health. Still, it's also significantly contributed to the high cost of healthcare, the disparity in outcomes across racial and gender lines, and Big Business-ification of health.

Speaking of big business, that brings us to where Whitaker and Baxter cross paths with the AMA.

The Freedom to Pay Up

In 1948, after 16 years of the New Deal, industry groups like the AMA looked forward to electing a more pro-business president. Harry S. Truman, who became president after FDR died shortly into his fourth term, runs as an unpopular incumbent. His challenger, Thomas Dewey, is widely expected to win.

Truman pulls off the surprise win and pro-industry forces mobilize to defeat further progressive reforms—including the national health insurance program Truman introduced in 1945—just six months after taking over the presidency. Among those aware of the plan, nearly 60% of Americans favor it, and only 25% oppose it. Fearing a loss of income, the doctors of the AMA vehemently oppose Truman's plan.

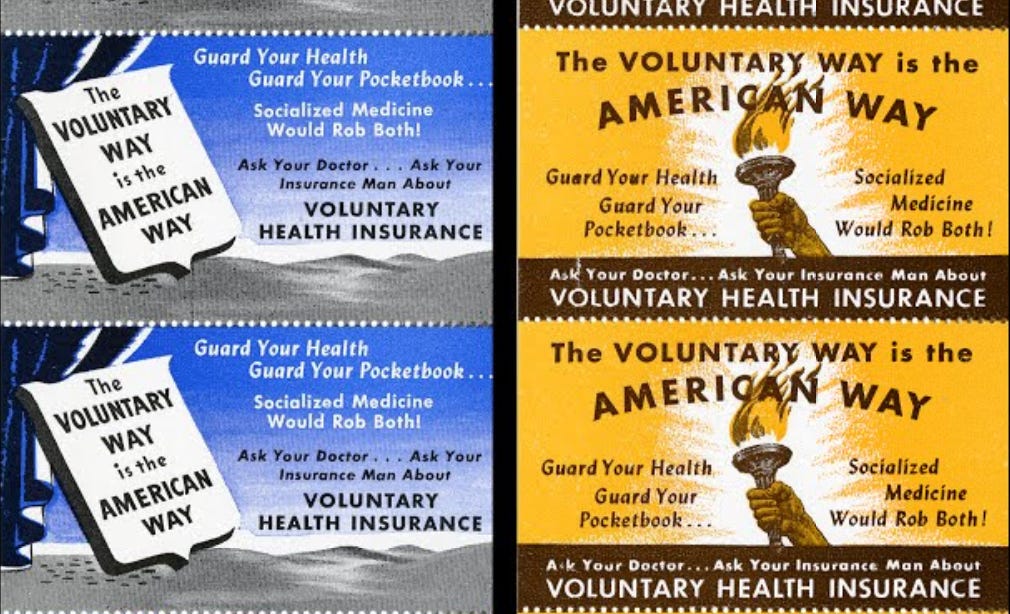

Whitaker and Baxter were a natural choice to lead the public relations effort against national health insurance. The California Medical Association had tapped them to help defeat Governor Earl Warren's state-wide health insurance program earlier in 1945. The campaign centered on encouraging Californians to voluntarily purchase coverage through the CMA’s Blue Shield plan, which offered prepayment for medical services.

The AMA came looking for a bigger, better sequel after Dewey's defeat.

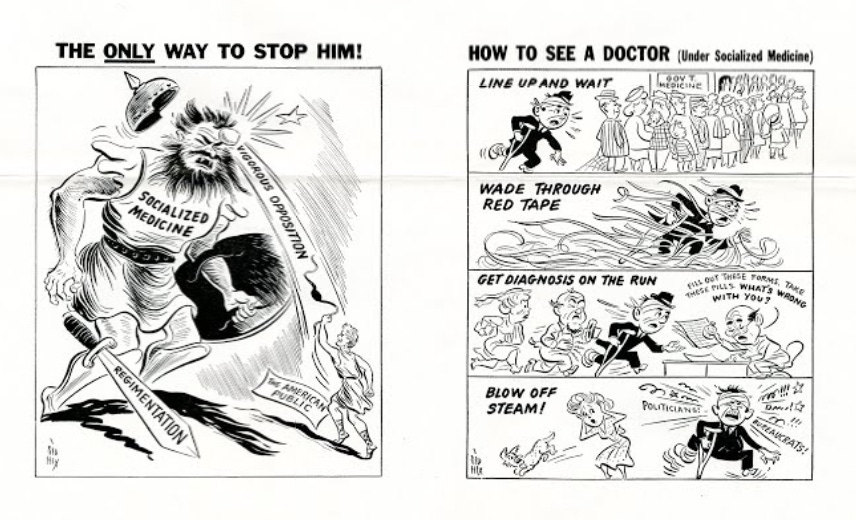

In 1949, when Whitaker and Baxter begin flooding the zone with messages about how national health insurance was a 'threat to health and a threat to freedom,' support for a national health insurance program falls, and opposition rises stiffly. By the end of 1950, the numbers have flip-flopped: 61% oppose the plan, 24% approve of it.

The conditions of the debate over national health insurance in 1948 look very different than the conditions today—even if the rhetoric is shockingly similar. The most common forms of health insurance were Blue Shield, prepaid medical services administered through state medical associations, and Blue Cross, prepaid medical services administered by hospitals. Separate insurance companies largely sold life insurance and didn’t cover medical services.

Today, we frame the debate as publicly funded healthcare versus insurance as a product you or your employer buys in the market. But the debate then hinged on normalizing and increasing demand for health insurance as a product in the first place. A new paper by two Harvard economists, Marcella Alsan and Yousra Neberai, finds that Whitaker and Baxter, along with the AMA, were successful. Not only did approval for national health insurance plummet, but purchases of private health insurance jumped. The message of that successful marketing campaign can be summed up in one word—freedom.

Whitaker and Baxter labeled first the California health insurance plan and then the national health insurance plan as "compulsory" insurance. That's like saying that Social Security is compulsory retirement savings or unemployment insurance is a compulsory rainy day fund. It's not exactly untrue—but it's a deliberate framing meant to contrast the program with the freedom to buy.

The campaign also promoted the idea that a national health insurance plan would constitute "socialized medicine." This echoed existing messages warning against the encroaching influence of communism and socialism in America.

Whitaker and Baxter added to the heat of the campaign by coordinating with other industries to place advertisements echoing these messages in newspapers across the country. Walgreens ran an ad asserting that "Free America has no place for a bureaucracy that stands between people and progress, between doctor and patient, between physician and pharmacist." The Dillon Implement Company exhorted, "Let's keep the Voluntary System in America! Voluntary insurance, Voluntary manufacturing, Voluntary buying and selling are all part of American freedom." A clothing retailer ran an ad contrasting rugged individualism with "ragged" socialism and supported the "doctors who are fighting for freedom."

The connection between business, consumption, and freedom was not a new invention of the 1930s and 40s.

It was baked into the first colonies in what is now the United States. It was manifest in our own brand of settler colonialism. It's enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution. Its transformation into the distinctly American spirit of capitalism was central to Max Weber's 1904 thesis about the Protestant ethic. Whitaker and Baxter’s campaign simply built on this existing foundation to make private health insurance synonymous with freedom in the mind of the American consumer.

However, the growth of the private health insurance industry, falling standards of care, and the exorbitant cost of it all is fueling a freedom-based backlash.

A Freedom-Based Backlash

Today, policies and proposals that aim to expand access to affordable healthcare are broadly popular—as long as surveys ask about them without raising the specter of partisan identity. According to Gallup, 62% of Americans believe the government should be responsible for ensuring all Americans have healthcare coverage. Fifty-one percent have a negative view of the healthcare industry while more than 60% have a negative view of the pharmaceutical industry. A majority of Americans are concerned about the cost of care (78%), dissatisfied with the quality of care (52%), and believe the healthcare system as a whole is either in crisis or suffers from major problems (69%).

The costs associated with the US's "voluntary health insurance" system are only partly financial. Another cost is our ability to access care at all. As evidenced by the outpouring of anger toward health insurance companies after the murder of the UnitedHealthcare CEO last week, people don't feel free to navigate the medical system as they or their doctors would prefer. People feel trapped by prior authorizations, managed care, and restrictions on what doctors or practices are approved by their plans. They're exhausted by the letters, forms, and phone calls required to beg for the health of their loved ones.

As early as the 1980s, scholars began noticing a trend of deprofessionalization among doctors and other health professionals. That is, health professionals were rapidly losing their autonomy and increasingly subject to the demands of health insurance companies. The health insurance industry shifted the terms of the doctor-patient relationship from a social one to an economic one. Doctors were now "providers;" patients were "members" of a health plan. And far from provisioning health, a health plan was merely an insurance product.

Drs. Deborah Ehrlich and Joseph Gravel argue that this deprofessionalizing and commoditizing language reinforces the notion that physicians are at the whim of insurance companies. Their own judgment is undermined, and their identity as trained experts who want to help the people they work with is erased. Doctors feel powerless and alienated, leading to worse health outcomes for patients and increasing rates of burnout among physicians and residents.

Ehrlich and Gravel write, "Deprofessionalization of physicians therefore harms the public by eroding trust, surrendering individual physicians' clinical judgment to utilitarian cost-cutting algorithms, creating conflicts of interest, and potentially dissuading altruistic, humanistic people from entering medicine."

Professionalization expels non-dominant practices and people, but deprofessionalization doesn't reverse that process.

Instead, commodifying and economizing the profession further entrenches status quo power—this time, in the form of financial products and capital accumulation. In turn, deprofessionalization opens the door to grift.

I like YouTuber and podcaster Matt Bernstein's definition of a grift, which is instructive here. He says that grift occurs when someone figures out what a potential or existing audience wants to hear (and, critically, buy) and then says that thing and provides that product. The grifter is "following their audience instead of their audience following them."

Think of all the people hawking supplements, extolling the virtues of cleanses, and warning against vaccines. They're part of a freedom-based backlash against an industry that makes people feel profoundly unfree. The political campaigns of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Dr. Oz and now their appointments to high-level policy-making positions are also part of this grift, part of this backlash. Companies that claim to increase access to popular drugs that treat everything from erectile dysfunction to ADHD to obesity to depression are part of the grift.

People want health, not health insurance.

If you can sell health outside the existing medical system, you've got a solid grift.

And that brings us back to where we started.

When I first started researching the origin story of America's terrible health insurance system, I expected to find a tale of greed and a pattern of hoodwinking voters. I did. But I also found something much bigger.

I found the vapid and disingenuous cooptation of freedom. I saw the same pattern of equating freedom with consumption that helps reinforce our vast wealth inequality today. I heard promises that strangely echoed the sales pitches of today's influencers and gurus. I found people scratching for freedom and winding up with something that more closely resembles a Happy Meal.

In philosophy and social theory, there is often a useful distinction between freedom from and freedom to. Freedom from connotes the absence of control and oppression, which we've been taught to think of as freedom in most liberal capitalist democracies. Freedom to, however, asks what conditions are necessary for us to live meaningful lives and pursue our desires. Importantly, there is no freedom to for me if there is no freedom to for you.

Our freedom—and the conditions that help us realize it—comes with social responsibility.

“To be free is not to have the power to do anything you like; it is to be able to surpass the given towards an open future; the existence of others as a freedom defines my situation and is even the condition of my own freedom. I am oppressed if I am thrown into prison, but not if I am kept from throwing my neighbor into prison.”

— Simone de Beauvoir

Financial freedom, health freedom, entrepreneurial freedom, educational freedom, time freedom, lifestyle freedom—these sales pitches can't offer freedom to. They only ever offer freedom from broken systems and social responsibility. I'll never look down on people who take action to rid themselves of the burdens of broken systems. Many people are understandably frustrated and desperate. Sooner or later, we all go looking for relief.

No, I save my scorn for those who promise relief they cannot provide. Who sell freedom in the form of exploitation. Who transform our authentic yearning for liberation into a Buy Now button.

It's true what they say: freedom isn't free. But it's not for sale either.

It's not a product you can buy off the shelf or a coach you can hire. If you're looking for freedom inside an online course, investment opportunity, or supplement bottle, I encourage you to reconsider. Shrugging off the nine to five job, building up your passive income streams, or avoiding the traditional medical system might ease some immediate pain, but it also makes it difficult to to realize what we need to create a truer, lasting, positive freedom.

In his new book, On Freedom, Timothy Snyder writes, “Negative freedom [that is, freedom from] is not a misunderstanding, but a repressive idea. It is itself a barrier, a barrier of an intellectual and moral kind. It blocks us from seeing what we would need to be free.”

The things we buy and the services we sell might very well be useful, even valuable, but they'll never be freedom.

I'm in awe of the Simone de Beauvoir quote. Her perspective on freedom as interdependent and ethical is profound. Thank you for sharing this—it’s given me a lot to think about.