Busyness Decoded: How to Limit What You Say "Yes" To

If you feel overcommitted or overwhelmed regularly, you’re not alone. In a 2022 survey, Gallup asked Americans to gauge their stress levels. Nearly half of the adults polled responded that they felt stressed daily. In a Pew survey in 2018, 60% of U.S. adults deal with sometimes being too busy or stressed to enjoy life. And another Pew survey, this one in 2016, found that 52% of respondents were usually trying to do two or more things at the same time.

You can probably file that last paragraph in the folder you keep labeled, “Thanks, Captain Obvious.”

There are plenty of systemic and material reasons for our busyness and stress. There’s a lack of reliable, affordable childcare for one. There’s the cost of healthcare for another. Then there are flimsy work arrangements, stagnant wages, unpredictable digital platforms, and the ever-increasing pace of economic and technological change. If it feels like the deck is stacked against our ability to live a life that’s only moderately stressful, it’s because it is.

Our busyness serves a function in the economy.

The busier we are, the more likely we are to purchase the products and services that claim to make us less busy. Think home delivery services. We’re also more likely to buy products that claim to counteract the effects of busyness. Think the entire wellness industry. To that end, the busier we are, the more likely we are to use debt to finance some of our countermeasures. And finally, our busyness renders us unable to meaningful interact with our communities and their political structures.

In sum, our busyness:

Creates markets for new products and even new industries

Increases our spending on palliative measures

Generates wealth via interest for lenders

Distracts us the public sphere (among many other things…)

Truth be told, I cringe a little every time I say, in the words of You’re Wrong About, “it was capitalism all along!” It begins to sound more like a conspiracy theory than rigorous systems thinking. Nefarious backroom dealing does happen in the financial sector and executive boardrooms (I think everyone can agree on that). But the negative impacts of the 21st-century economy tend to be more of a coalescence than an outright conspiracy.

There are violent and oppressive systems at play in the economy. And, there are ways we behave (as a result) that make the effects of those systems on us worse. Busyness is a systemic problem and it’s an individual problem. We might not be able to fix the systemic issues on our own.

But we can address the ways we are complicit in our busyness and stress.

In my book, What Works, I cite philosopher Alycia LaGuardia-LoBianco’s exploration of what she dubs complicit suffering. Complicit suffering, as a concept, acknowledges how we are harmed and disadvantaged by oppressive systems. But the concept also acknowledges the ways in which we make things worse for ourselves. I find this idea both humane and empowering.

LaGuardia-Lobianco never diminishes the violence and trauma many people experience as they move through the world (e.g., racism, misogyny, anti-queer and anti-trans bias, classism, etc.). And in fact, acknowledging the full depth of their impact is essential to understanding how we might be acting complicit with those systems. LaGuardia-Lobianco theorizes that one way to address complicit suffering is by shifting from self-sabotaging behaviors to self-care behaviors. She lists six steps for making that shift:

Avoid behaviors that exacerbate your suffering or put you in situations where self-sabotage is inevitable.

Refrain from harming yourself, including negative self-talk and self-deprecation.

Reach out to others and fill in your self-care gaps with care from external sources.

Practice noticing the sources of your self-sabotage and disempowerment.

Connect with others who reclaim their power and change their behavior.

Build an “agency emergency plan” so you know what resources you have access to shift your mood, relieve suffering, or find some peace.

It’s that last step that I want to explore today.

Flip the script.

So I’d like to offer a tool to put in your emergency kit for shifting self-sabotage to self-care and going from overcommitted to well-resourced. And that is managing for whole capacity—rather than simply time or money. In other words, don't ask, “Can I squeeze this in?” when presented with an opportunity. Ask, “Do I have what I need to do this well?”

Not only are we busy, but we are underwhelmed by the results of our relentless hustle. “Busyness is part of a broader set of structures that limit our choices and our ability to feel satisfied,” write sociologist Jackie Smith and anthropologist Joyce Dalsheim for openDemocracy.

Dissatisfaction is often self-perpetuating.

When we rush through a project in order to get through the next one on the list, we’ve probably cut some corners. So the product of that work is fine but it’s not remarkable. We’re happy enough to hit publish or ship it to the client, but we know it’s not as good as we could have done. The same thing happens in our personal lives, where the after-work or after-school rush means we often can’t savor our time with loved ones or enjoy a meal at human pace.

Of course, the answer to dissatisfaction or busyness isn’t to slow down. It’s not to practice mindfulness or notice the small things. Those are just more items on our shoulds and supposed-to-do lists.

To reverse busyness as a habit and dissatisfaction as a result, we must employ a limiter. A limiter is a device or setting that allows inputs up to a certain level but disallows inputs above that level. For instance, many vehicles used in the public sector have speed limiters—the vehicle simply will not go beyond a particular speed. In this case, our limiter is a simple question:

Do I have what I need to do this well?

Any time we’re inspired by a new idea, asked to take on a responsibility, or even invited to happy hour, this is the question we ask. The answer to “Can I squeeze this in?” is almost always yes because we’re so conditioned to push past sane boundaries and disregard our own limits. By the time many of us are willing to say, “No, I can’t squeeze this in,” we are way past the point of exhaustion. But when we ask, “Do I have what I need to do this well?” we have to make a different calculation.

First, we have to define what it means to do something well. That will be different for every project, invitation, or idea. Doing happy hour well might mean having one beer while getting some rare face-to-face time with a friend. Taking on a new responsibility and doing it well might mean having the time, energy, and emotional bandwidth to engage with everyone involved fully. Doing something well doesn’t necessarily mean getting a particular result—it’s the quality with which we approach the task.

Second, we have to do a calculation of total resources. There is no project for which “time” is the only resource needed. Some projects require little time but a whole lot of emotional bandwidth. Others require lots of time and a willingness to ask for support. Some projects require us to tap into our store of physical energy (e.g., training for a marathon). While other projects require us to tap into our mental bandwidth (e.g., taking a class).

So maybe a long-winded way to ask the same question is:

Do I have the resources to allocate to this project in order for me to feel satisfied with the way I tackle it?

This approach acts as a limiter because it imposes constraints on our busyness.

Time is only one of those considerations. We must also consider physical health, mental health, mental bandwidth, money, energy, emotional bandwidth, etc.

We may not be able to banish busyness entirely. Certainly, there are times when we’ll still have to say yes to things we don’t have the resources for—such is the power of the systems we exist in. But even then, this question can help us identify what resources we might need to rely on more heavily or bolster with complementary resources (e.g., creating more time by paying for help). The question can also help us identify where we could ask for accommodation. For instance, you might not have energy to take on a speaking gig that requires travel—but maybe you do have the energy to do a workshop and Q&A over Zoom.

Put it into practice.

As you consider everything that’s on your plate right now, I encourage you to reflect on these questions:

How have you added to your own busyness?

What’s on your list that you don’t have the resources to do well? What’s on your list that you do have the resources to do well?

Are there tasks you could drop to reallocate those resources to projects that need them?

Are there tasks for which you could ask for accommodation to better match your capacity?

Is there a particular resource you feel especially low on? What’s on your plate that’s draining that resource?

This essay is based on a conversation I had with Charlie Gilkey and Jenny Blake about capacity, time, and energy. Listen to it here!

Work has evolved. The way we work has not.

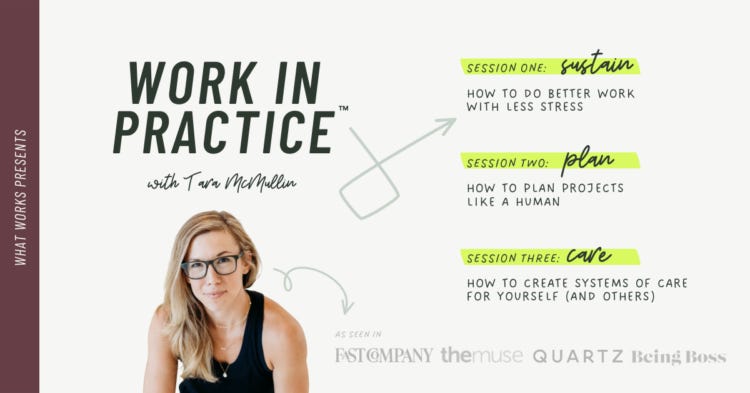

We need a new vision for work that creates the capacity for creativity, critical thinking, and health. Join me for a 3-part workshop called Work In Practice to create your own culture of practice.