Banking on Crisis

Chaos creates opportunities—and even accidental celebrities. But I wouldn't bank on it.

This is a follow-up to my previous post, “Influence in Crisis.”

You don’t have to read that one to read this one. But you might be better off reading that one instead of this one if you don’t want to go deep into the weeds with me!

We often anthropomorphize the algorithm.

We complain about what the algorithm wants or likes as if it makes choices that intentionally help or harm us. Of course, the algorithm doesn't want or like anything. It doesn't intend to help or harm us.

Algorithms don't have any form of agency or awareness. They are simply systems designed to turn certain inputs into their designers' desired outputs.

There has been enough research on the function of social media algorithms to know that high-engagement content will likely result in a distribution that exceeds the norm. Content that expresses outrage, anxiety, or awe is also more likely to receive a high level of engagement. This is even more likely when that content signals a particular group identity (e.g., a shared diagnosis, political party, fan interest, etc.).

This isn't because algorithms (to the best of our knowledge) are explicitly coded to seek out content with high-arousal emotional trigger words or signals of group identity. It's not because platform founders like some emotions or groups and not others. It is simply a function of engagement. And engagement, from the platform perspective, drives the business model.

For a social media platform, engagement means the user will likely spend more time on the site or app. More time on site means more available space in the feed to run ads, as well as more data (i.e., the information acquired through user behavior) with which to target those ads.

And that brings us back to the phenomenon that I highlighted in my previous piece: the crisis influencer:

by accident or design, becomes a vector for emotional and moral sensemaking in a crisis and, as a result, gains influence with a growing audience, primarily via social media.

The user who is ready with a steady supply of information, hot takes, or sensemaking in a crisis will likely create exactly the type of content that algorithms privilege. If even one of their posts gets outsized traction—goes viral—they often experience a bump in distribution and engagement more broadly. The crisis influencer emerges from the fray.

In this piece, I'll examine the mechanics of this type of growth, the economic incentives that interact with those mechanics, and the experience of the person who finds themselves in the center of the chaos. I hope to make sense of the crisis influencer phenomenon so that you have a useful framework for analyzing your own experience and can make informed choices about the content you create, the people you follow, and the uncomfortable feelings that arise at the intersection of responsibility and opportunity.

As I said in Part I, my intention isn't to call anyone out. I'm interested in understanding this phenomenon—how it occurs and why its results are so consistent across platforms and perspectives. 'Crisis influencer' probably sounds a bit loaded, a derogatory term for a creator who may or may not chosen this path. I don't mean to use the label as an insult. I want to look at the phenomenon neutrally, as a fact of our current media environment rather than an indictment of individual behavior or happenstance.

The Exception to the Rule

I used to scroll Twitter, Instagram, or more recently, Substack Notes. Today, I almost exclusively get my social media fix at Bluesky. Bluesky is a Twitter clone—indeed, it was a side project of Twitter in the pre-Musk days—and it has quite a few things going for it.

Bluesky, still a microscopic platform compared with the old guard, has seen massive growth in the last six months. Another wave of new users flocked to the platform in the week since the US presidential election. An independent journalist I follow posted that they were gaining two thousand new followers per day as people flee Twitter to join up.

I'm watching the platform's explosion of growth with interest and curiosity. And I'm watching as Bluesky's early movers and main characters react to this period of handwringing and dismay, as well as the influx of attention they are receiving.

Out of the box, Bluesky's main feed is purely chronological rather than algorithmically curated. The skeet at the top is always the last skeet that someone you follow posted or reposted. Bluesky's key differentiator is how it enables user-generated moderation. The platform regularly rolls out new ways for users to finesse and curate their experience—and pass those tools on to others. Users build feeds, starter packs (groups of recommended accounts to follow), and block lists, which can then be shared with other users.

Bluesky is explicit in its intent to break from what has become the norm in platform development. So it might seem like an unlikely focus for a discussion of crisis influencers, who typically emerge via those design norms. But it's an exception to the rule that demonstrates how the mechanics, economics, and experience of the crisis influencer phenomenon are more baked into our social interactions than we realize.

The Rule

As previously stated, strong emotions drive engagement on social media platforms. Engagement results in algorithmic distribution—that is, what content people see when they open the app. And distribution is a precondition for growing an audience.

To state the obvious, crises generate strong emotions. Crisis conditions and their corresponding emotional states make producing engaging content (as defined by platforms) easier. Thus, audiences can be more easily built during a crisis through the leverage of high-arousal emotions.

The political, economic, and/or media conditions of a crisis focus a social media creator's content in a way that allows their message, positioning, and presentation to break through the noise. The crisis influencer is reborn in chaos, aided by platform design and social psychology.

Luckily, some social psychologists offer a useful model for thinking about this.

Moral-Emotional Expression

William Brady, a social psychologist who studies how emotional dynamics impact social networks, and fellow researchers found that content they describe as moral-emotional expression is particularly engaging on social media platforms. Moral-emotional content combines high-arousal emotions with positions that indicate a particular way of evaluating right or wrong, just or unjust, on a societal level. It also signals group identity, another factor in engagement, as it reflects the moral and epistemic positions of the creator's group.

By incentivizing engagement, platforms incentivize moral-emotional content. If engaging content is rewarded with distribution, then moral-emotional content is rewarded with distribution.

A crisis inspires moral-emotional content by providing the material conditions for clarifying a moral position and stoking the high-arousal emotions that correspond to it. The wider the impact of the crisis, the more content consumers there are to engage with the moral-emotional content it provokes. A high-impact crisis that leads to high-impact moral-emotional content creates the conditions necessary for rapid attention realignment.

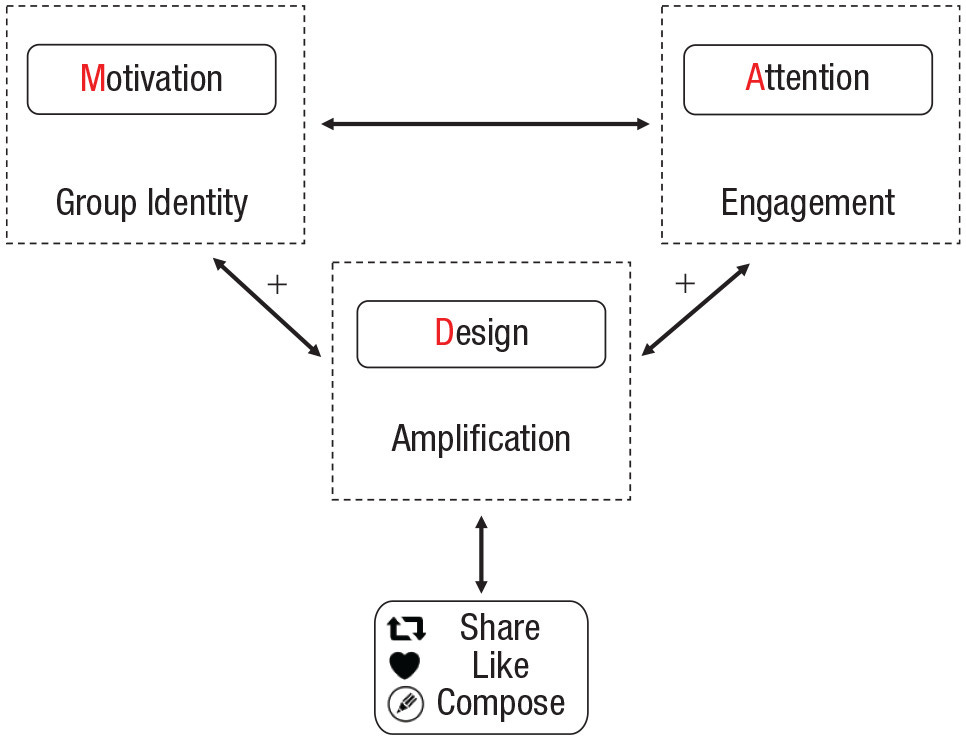

Brady et al. devised the motivation, attention, design (MAD) model to explain this process. The model shows how our motivation to express or align with our group identities, combined with how our attention is allocated through engagement, becomes amplified by the design of the platforms we use for consuming and sharing social media.

The Exception

While we've come to expect that algorithms use the input of shares, likes, and comments to output the content distribution that maximizes platform objectives, Bluesky demonstrates that the MAD model can also be applied to chronological and human-curated feeds.

On Bluesky, the motivation to signal group identity is still a major factor in what users share. That motivation isn't dependent on what platform someone uses; it's basic social psychology. Attention isn't directed algorithmically, but engagement is still the primary determinant of how much attention is directed to a particular post or user.

While it lacks algorithmic curation, Bluesky's moderation features largely favor the expression of group identity. A user can create a Starter Pack of, say, nature photographers who use ALT text or board game publishers or users in the autistic community (which I was added to and brings me new followers every day even though I don't post often).

Creating or following a Starter Pack is a direct expression of group identity because it explicitly connects the user to others who identify as part of the group. Further Feeds, Lists, and Block Lists work similarly to give users control over how they engage with and express their group identities. These platform features allow users more control over their network experience, which inevitably impacts the moral-emotional content they consume and share.

One more thing: Brady also determined that users learn what kinds of expression are welcome on a platform by observing what others post. Specifically, he and fellow researchers studied the social learning that influences expressions of moral outrage. They found that users learn from feedback (e.g., likes and shares) and, in turn, adjust their behavior. Due to the way outrage functions in social media, this most often means we learn to express more outrage because it gets more positive feedback (even if some of that positive feedback is negative).

Now that I've examined the mechanics of audience growth during a crisis by unpacking how moral-emotional content leads to greater engagement, which leads to greater distribution, I will turn to the economic incentives that intersect with the rise of the crisis influencer.

Influencers as Hackers

The crisis influencer—by design or by accident—is tasked with finding new ways to express old moral-emotional positions. Initially, the crisis provides a scaffolding on which to build anew. Crisis influencers can express outrage toward a new target, make sense of breaking news, or pass on what they're learning from friends or sources. It's received as new because the crisis is new, even if the moral-emotional position itself is long-held.

The work of the crisis influencer fits theorist McKenzie Wark's definition of the 'hacker:'

What I call the hacker class has to produce difference out of sameness. It has to make information that has enough novelty to be recognizable as intellectual property, a problem that landed property or commercial property does not have. By hacker class I mean everyone who produces new information out of old information...

Whereas other work revolves around the production of sameness (e.g., the same paperwork, the same experience, the same widgets, etc.), hacking produces difference—a different take, a different emotion, a different design, or word choice, or metaphor. Instead of an assembly line or cubical that values efficiency through sameness, the hacker works within a vector.

The workplace nightmare of the worker is having to make the same thing, over and over, against the pressure of the clock; the workplace nightmare of the hacker is to produce different things, over and over, against the pressure of the clock.

The vector is the digital infrastructure through which information flows and the interface that turns behavior into data. Meta owns the vector through which a literal wealth of user behavior allows it to model, predict, and shape future behavior. ByteDance does the same with TikTok. Alphabet does the same with Google.

Not only do these companies need the information to keep flowing, but they also need conditions to change constantly so that their models and predictions are valuable. It's easy to predict how a stable system will behave, but it's hard (and therefore much more valuable) to predict how a system in constant crisis will behave. Chaos is good business for the people who own the vectors.

Hackers can’t be managed like farmers or workers; they are not the same as either class. There’s no relation between the units of labor time and the units of value produced. Something cooked up on the spur of the moment might have enormous value. Long hours of slog might end up being for nothing. Being exempt from routine work is not really all that glamorous in either story, as it just brings uncertainty, frustration, pressure, and (for some) madness.

The worker has a clear set of incentives that shape the economic conditions of their work: to perform the job reasonably well and produce the required output in a set amount of time in exchange for a wage. The incentives that shape the economic conditions of the hacker are ambiguous at best. Status, attention, social proof, resonance—the hacker works (largely throwing spaghetti at the proverbial wall) to output information that triggers these responses. Rarely are those outputs the job, though.

Hackers (mostly) don't get paid for hot takes, but hot takes often shape their employability. This is a condition that is both stressful and precarious.

As long as a crisis influencer can produce the kind of moral-emotional content that drives Brady's MAD model, the influencer produces attention in the form of a growing audience and expanding influence. How that turns into compensation, though, is tenuous. Maybe they become a pundit, a columnist, or an author. Maybe they start a consultancy or embark on a speaking career. Maybe they attempt to convert their influence in one area into influence in another.

However they make their way to financial compensation (if they do at all), the conditions that created the opportunity are constantly at risk of changing. When crisis influencers emerged in the first weeks of the Covid pandemic, they had plenty of opportunities to consult on online events, teaching, or meetings. Later, those opportunities quickly evaporated as people returned to the office and school. A few months after the pandemic began, corporations in (brand) crisis realized they better hire a DEI consultant. A group of unintentional crisis influencers gladly signed big contracts to do the social change work they fervently believed in. A year later, budgets were trimmed, and those consultants were often the first to go.

Influence Isn't Capital

It is possible to leverage influence into a more stable career or business. But I wouldn't bank on it. Influence and the moral-emotional expression it's based on aren't capital. It's labor. What's more, it's distinctly ephemeral labor. Every time you hit publish or post, you must start thinking about the next thing you can publish or post.

We have no regulatory system for creating emotional or moral property the way we do intellectual property. Our systems for copyright, trademark, and patents help turn brands, works of art, inventions, or systems into property that an individual or corporation can own. But no form of property makes an emotional or moral position ownable. And there shouldn't be. However, it would make a great conceit for a sci-fi novel.

Moral-emotional expression as labor shares much in common with Arlie Russell Hochschild's description of emotional labor, unsurprisingly. Hochschild argued that emotional labor could be just as dangerous as physical labor, but that danger was to our mental and emotional bodies rather than our physical ones. Similarly, moral-emotional expression as labor is quite dangerous. Not only are the crisis influencers at risk of mental and emotional injury, but they also risk moral injury.

Moral injury occurs after witnessing or participating in actions that violate a person's core values—often experienced in war. A crisis influencer may experience moral injury because even though they seem to be expressing an authentic moral-emotional position, platform incentives put them in a position in which they feel compelled to raise the stakes, embrace conspiracy, or induce fear, anxiety, and outrage in their followers for the stake of the algorithm.

Maybe it's moral self-injury.

Saying Something

"Sensemaking starts with chaos," explains organizational psychologist Karl Weick. The unexpected outcome, the unpredictable crisis, the shock and awe of waking up in a world that no longer makes sense (or merely a reminder that it never did) is an appropriate situation for sensemaking. A necessary situation for sensemaking. It's an appropriate time to stand up, speak out, and gather together.

We feel a responsibility to say something. We fear the consequences of saying the wrong thing or saying nothing at all. We wonder what others are thinking and how people in our group are reacting. We want guidance, and many of us feel compelled to guide.

However, a crisis is a hazardous and often life-altering time to come into the power of influence. It's rarely a good time to make career or business decisions. Sometimes, it can't be helped—I think there are more accidental crisis influencers than opportunistic ones. No matter what position you find yourself in a crisis, the situation demands we take extra care when it comes to how we create and consume media.

That very last sentence is exactly what I'm doing when it comes to consuming media. I'm certainly not creating any. Even though I've stepped away from social media and the news my anxiety is high, but it would be higher with all of the takes flying around. Also, a term comes to mind as I read both pieces: disaster capitalism. Whether it's intentional or not on the part of the influencer, that's what I'm seeing. Anyway, I enjoy analyzing the thing behind the thing.