Adopting the Perennial Mindset

Our conventional narrative about life and work doesn't match the facts on the ground anymore. Mauro Guillén argues that we'd all be better off with a "perennial mindset."

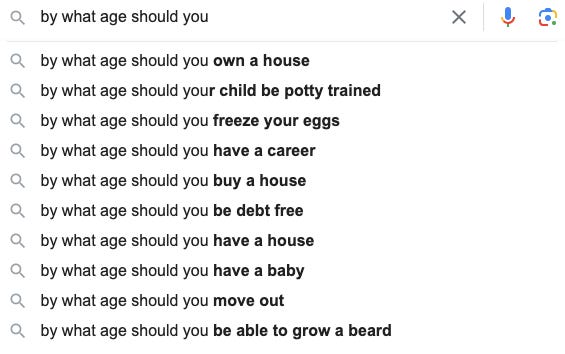

On a whim, I open a Google tab and start to type: "By what age should you..."

Google suggests I might be looking for the age by which you should own a house, freeze your eggs, have a career, move out, have a baby, be debt free, and other predictable life milestones.

Of course, the idea of a milestone is that it represents a predicted passage from one stage to another. You can't really have a "milestone" if you're not on a journey with a clearly delineated route.

Babies have certain developmental milestones to watch for. Not every infant crawls or says its first word at the same time, of course. Nor do they need to. But keeping track of those developmental milestones gives parents and healthcare providers certain clues of what's going on with this new little person.

For the last century or so, we've subjected teens and young adults to a similar set of development milestones.

Graduate high school at 18, go to college or enter the job market, move out of the family home sometime in the early 20s, find a partner, get married, buy a house, have a kid. Work, and work, and work. Retire at 65. For as "natural" as that sounds to most Americans today, it's a pattern of life that's a mere footnote in the annals of human society.

A new book, The Perennials: The Megatrends Creating a Postgenerational Society, tells a very different story about what life could be like in the 21st century. Mauro Guillén, the author, is a sociologist, political economist, and a management educator, as well as the Vice Dean of the MBA program at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. His thesis is that the facts on the ground just don't line up with the expectations we put on ourselves and others for how we move through life—and it’s time for change.

If people could liberate themselves from the tyranny of “age-appropriate” activities, if they could become perennials, they might be able to pursue not just one career, occupation, or profession but several, finding different kinds of personal fulfillment in each. Most importantly, people in their teens and twenties will be able to plan and make decisions for multiple transitions in life, not just one from study to work, and another from work to retirement.

— Mauro Guillén, The Perennials

But let's start with how we got here.

Keep reading, or listen on the What Works podcast:

The Sequential Mode of Life

"We introduced two major innovations," Guillén tells me. The first was compulsory schooling—which was law in every US state by 1918. Sending kids to school "effectively separated the first stages: early childhood from when we are supposed to attend school."

Around the same time, thanks to labor organizing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we also saw the rise of the pension. "That also created a boundary between our working years and our retirement," he explains.

These innovations essentially divided life into four stages—what Guillén calls the sequential mode of life. "When we're very little, we play. Then, we go to school. Then, we work. And then, finally, we retire. Those are the four stages in life."

We get the message—through family, media, teachers, even potential mates—that we need to proceed through each stage at the right time. Moving from one stage to another at the right time is sort of proof of your fitness for society. What's more, we get the impression that comfort and success are ours as long as we don't deviate from the proper path through life.

But not everyone sticks to the proverbial straight and narrow. "People who miss a transition are in deep trouble," Guillén observes.

Late Bloomers

I return to Google and type: "obstacles late bloomers face." The results are all about dispelling the notion that there are obstacles to face as a late bloomer. Late bloomers, I learn, bring all sorts of strengths to the workplace. They might even be happier in the long run!

Cool, fine. I totally agree that the value someone brings to an organization or a community doesn't change based on what age they graduated from college or when they got married.

But real structural and financial difficulties come from not "settling down" when you're quote-unquote supposed to.

In the United States, however long it takes to settle into a full-time job is time your access to healthcare is precarious. It's time you're not saving for retirement or enjoying an employer contribution to your 401k. You might move around frequently and have onerous amounts of paperwork to complete. And that can mean you might find it difficult to vote or become an active member of the community.

These are largely privileged problems. People of color, immigrants, disabled people, and poor people face greater structural pressure to move from one stage of life to the next "on time"—or even to move out of the childhood and schooling stages before those stages are actually over.

So the challenge of being a late bloomer isn't only social stigma. There are financial, civic, health, and quality of life issues too.

But it seems that the sequential mode of life and its imperatives don't seem to match the reality on the ground today.

Times are Changing

I don't know if you noticed this—but life looks pretty different today than it did in the 1930s, 1950s, or even the 1980s! We're living longer (mostly), more women are working, we go to school longer, etc...

"There are a number of trends that are essentially converging," Guillén tells me, "And they are presenting us with these new situations in which we need to be more flexible." He says that not only are we living longer, but we're healthier for longer. And that means we have more opportunities to try new things, make changes, and try on different lifestyles.

We're also, of course, experiencing rapid technological change. Industries evolve quickly—and so do the jobs that they create. Whether or not the robots are coming to take our jobs, our jobs probably won't look the same in another decade. That means career change will become a fact of life for more and more people.

"All of those things," observes Guillén, "they're essentially inviting all of us—100% of us—to rethink the way in which we think about life, and especially about when we learn, when we work, when we retire, and so on and so forth."

Plus, this is an opportunity to address groups of people who've missed out or fallen behind for a variety of reasons. Guillén cites people with substance abuse issues, teenage mothers, and people who drop out of high school. By changing the narrative about the ideal sequence of life (along with the social, economic, and political supports required), we can create new on-ramps to a meaningful life.

Expectation Management

Back when I was dealing with my own lack of transition from one stage to the next, I delivered a performance review to one of the full-time team members at the Borders store I managed. This person was a competent employee who didn't have any major issues but wasn't a superstar.

The review was fine.

The employee asked about their schedule, telling me that their dad had said they really should be working a "regular" schedule by now—that is, a Monday-Friday, 9-to-5 schedule. The dad expected that, by your early 20s, you should have "graduated" into a normal job with a normal schedule.

Unfortunately for this team member's dad, we were working in retail. Our store was open from 9am-10pm every day. Literally no one on staff worked a quote-unquote regular schedule.

I have no idea what I said at the moment—other than something along the lines of "That's not going to happen." But I've often thought about that moment over the last 15 years. While I was surprised that this team member would ask for that kind of schedule when no one else had it, what really surprised me was the father assuming that the transition to a 9-to-5 job was still a valid expectation.

The fastest-growing sectors of our economy don't accommodate a 9-to-5 schedule. The most attractive jobs in our economy don't constrain themselves to 9-to-5 schedules. Even the notion of a "full-time job" is coming into question.

All that to say that so many of us are operating with expectations of how life is supposed to go that just don't reflect the reality on the ground. And while I wholeheartedly believe we can make the reality on the ground so much better, I also believe we need better ways to navigate what is. To do that, we need a better map to navigate by.

Guillén tells me that he didn't write The Perennials only for people in their 40s, 50s, or 60s. It's also for the 20-somethings who are looking at the situation in front of them and trying to imagine a different way forward.

Easing The Stress of Sequential Living

How might life be different for those 20-somethings if they started to imagine life in 10 or 15-year increments?

"I think it releases a lot of the pressure that we put on teenagers and people in their early 20s," explains Guillén, "that they have to make up their minds as to what it is that they want to do for the rest of their lives. How can you ask somebody that young to make that decision?"

As a soon-to-be 41-year-old, I can say that I really needed this perspective in my 20s. Even my teens. And it's one I'm trying to share with my daughter now.

No matter how many articles there are giving parents or teens permission to relax about college majors and choosing careers, we think of college as career prep more than ever. The whole student debt industry is based on the marketing message that college is an investment in future earnings. And to make good on that investment, not only do we need to get the education, but we need to have picked the right education—the kind that's going to see us through the next forty or fifty years.

Of course, that's just not realistic. It never was—but it's really not now, given the rapid change in the economy.

Guillén recommends pulling companies and the government (the largest employer in every country, including the US) into this change. To facilitate the inevitable transitions that occur over a lifetime, we all need to get more comfortable with older students and older entry-level workers. We could create programs and incentives that help ease that friction—while at the same time creating opportunities across the labor force.

I Believe the Children Are Our Future

As I mentioned, I'm now navigating college and career conversations with my 15-year-old daughter. She's at the point where she has careers in mind that she might like to pursue, but they're also subject to change from one month to the next. She seems to think about college choices in terms of, first and foremost, whether or not a school has a good field hockey team and, second, what kind of job she wants to have.

That's (mostly) different from how I thought about college at her age. I wasn't thinking about jobs so much as I was thinking about what I wanted to study. As a result, I went to a small liberal arts college and got a degree in the humanities. It was a wonderful experience—and it in no way prepared me for any sort of career other than that of a full-time student.

I've mostly succeeded at that, even if I don't have the fancy degrees to show for it!

However, my liberal arts education has made me a much more resilient and adaptable adult. I know that I can train myself to do just about anything I want to do—and I have a broad base of critical thinking skills to make that possible. I'd be lying if I said I didn’t emphasize the benefits of a liberal arts education when I talk to my daughter about college. But, of course, I'm up against the evolution of higher education that's taken place over the last 50 years and turned college into job training.

Guillén says that some jobs will always require specialized, intensive training (e.g., pilots and doctors). But more and more, companies are looking to train their workers. Instead of hiring people who can dive in on day one, they're more interested in people who bring a learner's mindset to the job. They want people with interpersonal skills, the ability to work in teams, a level of comfort with uncertainty, and strong communication skills.

He encourages students to think about what they're passionate about without constraining themselves too much. Learn math, learn communication (especially a second language), and learn social skills—no matter what career is currently appealing.

Adopting the Perennial Mindset

A perennial, Guillén tells me, is someone who isn't constrained by their age and what they're "supposed to" be doing at any give stage of life. "The perennial mindset is telling you," he says, "look, you don't have to achieve everything by age 22 or 23." Instead, we can think longer term—knowing that things will change. We might go back to school, change industries, learn a new skill, or even stop working for a time before we get back to it.

By recognizing the inevitability of change, we can take the pressure off of younger people and, hopefully, start to reverse the mental health challenges they face.

Similarly, for people later in their career, we don't have to wait for retirement to get out of a miserable situation. We can take some of the pressure off of sticking with that career we chose 30 years ago or the financial preparations needed to stop working. Work can be a way for older adults to stay active and connected to friends.

I will say that I'm skeptical of any retirement solution that hinges on working rather than resting. But it seems that Guillén is proposing something that broadens the definition of work. I can imagine a world in which older people are integrally connected to their communities through forms of work that look more like mentoring, cultural production, and support. And really, this already exists—we just have to recognize the real value it adds to our society and compensate people for it.

Maybe It's All About Retirement?

If instead of compartmentalizing learning, work, and leisure by age we enable people to choose the mix of activities they desire at each stage of life, we might be able as a society to help people achieve financial security, fulfilment, and equity.

— Mauro Guillén, The Perennials

It strikes me that so much of Perennials and my conversation with Guillén turns on the question of retirement. That's probably partially due to my own stage of life. But it's also certainly due to how elusive the promise of retirement feels to just about anyone under, say, 55 today.

Note: Google suggests I complete “Will millennials…” with “…be able to retire.”

Retirement may or may not be on the minds of students taking out massive loans to pay for college. But the pressure to not only make enough money to live on now but enough money to save for the future is very real. Sure, a living wage and paid time off are nice—but does this job come with an employer contribution to my 401k?

Most millennials, like me, look at our "retirement savings" (or lack thereof) and feel really, really behind. And those baby boomers and Gen Xers1 who have reached retirement age may be wondering what's next—and why they're feeling so disconnected from the rest of the world.

One of the easiest ways to ease these burdens is through quality-of-life guarantees. Things like a livable minimum wage, expanded union membership, a strengthened social security program, guaranteed healthcare, guaranteed housing, and, yes, a universal basic income. These policy solutions go beyond what Guillén suggests in the book—which are still fairly progressive and certainly subversive of the status quo.

Quality-of-life guarantees could help people make life transitions—at any age—with more ease. And while these guarantees do benefit individuals directly, they also benefit our society. Fewer people scraping by, falling behind, or burning out because of unreasonable expectations is an overall cultural and economic good.

Vast demographic and technological transformations are gradually bringing about postgenerational ways of living, learning, working, and consuming. As a result, it’s becoming increasingly possible to liberate scores of people from the constraints of the sequential model of life, leveling the playing field so that everyone has a chance at living a rewarding life.

— Mauro Guillén, The Perennials

I came away from The Perennials and my conversation with Mauro Guillén really energized—if also profoundly disappointed that I didn't have it to read 20 years ago! The way I see it, the perennial mindset and a socio-political structure built to support people at every age is long overdue.

New workshop for premium subscribers!

Self-sabotage—any of the myriad ways we can make it harder on ourselves to make or do the things we want—is something most people deal with. And once you're in the self-sabotage cycle, it can be hard to break out. Self-sabotage behaviors tend to feed other self-sabotage behaviors.

In this workshop for Premium Subscribers of What Works, I'll share what I've learned about breaking the self-sabotage cycle, cultivating follow-through, and working toward excellence.

"Follow-through isn't about the quantity of energy you bring to a project. It's about the quality of energy. It's finesse."

This workshop is based on Chapter 11 of my book, What Works: A Comprehensive Framework to Change the Way We Approach Goal-Setting.

Date: August 24, 2023

Time: 12:30pm ET (New York)/9:30am PT (Los Angeles)

Price: Included with your premium subscription!

I had to look up whether you’re supposed to capitalize the names of generations. The MLA says that names like “millennial” and “baby boomer” are lowercase. But generations with a letter in them (e.g., Gen X and Gen Z) are capitalized. The Greatest Generation, however, is also capitalized. But apparently, “the silent generation” is not capitalized. Go figure.

I like Rose Marcario's definition of retirement in this interview:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/18/business/rose-marcario-patagonia-corner-office.html

"The reality is I feel like I’m just entering a different stage in my life. In the Vedic system, there are four stages of human life. The first is the student, the second is the householder and the third is retirement. The Sanskrit word for the third is actually vanaprastha, which means going into the forest. The idea is that during this stage of your life, you hand over your day-to-day responsibilities to the next generation and become an adviser and a teacher. I’m literally living in a rainforest, so it’s more than a metaphor in my case."

But you're so right about the precarity around health care and enough money. It keeps people trapped in "jobs" that are producing nothing but carbon dioxide and billionaires. That's a feature, not a bug.